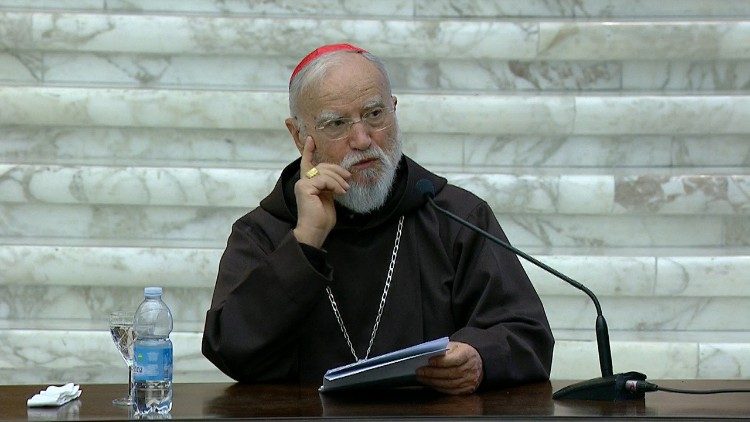

On Friday, February 26, 2021, in the Paul VI Hall, the first sermon of Lent was presented by the Preacher of the Papal Household, His Eminence Cardinal Raniero Cantalamessa, O.F.M. Cap.

The theme of the Lenten meditations is: “But who do you say that I am?” (Matthew, 16: 15) – Christological dogma, font of light and inspiration”. The subsequent Lenten Sermons will take place on Friday 5, 12, and 26 March.

******

Cardinal Raniero Cantalamessa ofmcap

‘REPENT, AND BELIEVE IN THE GOSPEL!’

First Sermon, Lent 2021

As usual, we shall devote this first meditation to a general introduction to Lent Tide, before delving into the specific subject we have planned once we have completed the spiritual exercises of the Papal Curia. In the Gospel of the First Sunday of Lent of Year B, we heard the solemn proclamation with which Jesus began his public ministry: “This is the time of fulfillment. The kingdom of God is at hand. Repent, and believe in the gospel’ (Mk 1:15). We would like to meditate on this ongoing call of Jesus to repentance.

In the New Testament, conversion is mentioned in three different moments and contexts, each highlighting a new component of the process. Three passages jointly give us a complete idea of what the Gospel metanoia is about. We will not necessarily experience all those three components together, with the same intensity. A different kind of conversion is provided for in each season of life. It is important for each of us to identify the one that suits them right now.

Repent, that is believe!

The first kind of conversion is the one that resounds at the beginning of Jesus’s preaching and is summed up in the words: “Repent and believe in the Gospel!” (Mk 1:15). Let us try and understand what the word ‘conversion’ means here. Before Jesus, converting always meant a ‘going back’ (the Hebrew word shub means reversing route, going back on one’s own steps). It defined someone’s course of action when, at a certain time in their life, they realize they are ‘off track.’ Then they stop, to think it all over again; they decide to go back to observing the law and rejoining their covenant with God. Conversion, in this case, has an essentially moral meaning and suggests the idea of something painful to do, such as changing habits, stopping doing this or that.

On Jesus’s lips that meaning changes. It is not that he enjoys changing the meaning of words, but that, with his coming, things have changed. ‘This is the time of fulfillment. The Kingdom of God is at hand!”. Converting or repenting no longer means going back, to the old covenant and to the observance of the law, but rather it means leaping forward and entering the Kingdom, grabbing salvation reaching out to men and women for free, out of God’s own free and sovereign initiative.

‘Repent and believe’ does not refer to two different and subsequent things, but to the same fundamental act: repent, that is believe! “Prima conversion fit per fidem”, says St. Tomas Aquinas: The first conversion consists in believing.[1]All this calls for a genuine act of ‘conversion,’ a deep change in the way of seeing our relationship with God. It requires a shift from the idea of a God that asks, orders and threats, to the idea of a God that comes to us with full hands to give us everything himself. It is the conversion from ‘the law’ to ‘grace’ that St Paul cherished so much.

‘Unless you turn and become like children …’

Let us now listen to the second passage in the Gospel, where conversion is referred to again:

At that time the disciples approached Jesus and said, “Who is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven?” He called a child over, placed it in their midst, and said, “Amen, I say to you, unless you turn and become like children, you will not enter the kingdom of heaven. (Mt 18.1-3).

This time converting does indeed mean turning back a long way as far as our childhood! The very verb that is used, strefo, points to reversing directions in a march. This is the conversion of those who have already entered the Kingdom, have believed in the gospel, and have been serving Christ for a long time. It is our own conversion!

What is the assumption underlying the discussion on who is the greatest? It is the idea that the main concern is no longer the Kingdom, but the place the apostles have in it, their ego. Each of them was somewhat entitled to aspire to be the greatest: Peter had received a promise of primacy, Judas held the money box, Matthew could claim he had left more than the others, Andrew that he had been the first to follow Jesus, James, and John that they had been on Mount Tabor with him… The fruits of this situation are clear: rivalry, suspicion, mutual comparisons, frustration.

Jesus suddenly removes the veil. Forget being first: you will never enter the Kingdom that way! What is the remedy for that? Turning, completely changing perspective and direction. Jesus puts forward a genuine revolution. It is necessary to shift the center from yourself and to re-center yourself on Christ.

More simply, Jesus invites the apostles to become like children. For them going back to being children meant going back to their original call on the shores of the lake or at their working desk: without personal demands or titles, mutual comparisons or envy and rivalries. Their only wealth then was Jesus, his promise (‘I will make you fishers of men’), and his presence. Then they were still fellow travelers; they did not compete for the first place.

For us too going back to being children means going back to the time when we discovered we were called, to the time of our priestly ordination, of our religious profession, or to the time we first truly encountered Jesus. When we said: “God alone is enough!” and we believed it.

‘You are neither hot nor cold’

The third context in which a pounding invitation to conversion is repeated is that of the seven letters to the Churches of the Book of Revelation. The seven letters are addressed to people and communities who, like us, have long-lived a Christian life and in fact play a leading role within them. They are addressed to the angel of the different Churches: ‘To the angel of the church in Ephesus, write this…’ Such title cannot be explained but by direct or indirect reference to the shepherd of the community. It is unthinkable that the Holy Spirit should blame the angels for faults and deviations reported in the different churches, or even more that the call to conversion be addressed to angels instead of men!

Out of the seven letters to the Churches, the one that we should most meditate on is the letter to the Church of Laodicea. We are quite familiar with its harsh tone:

I know your works; I know that you are neither cold nor hot. I wish you were either cold or hot. So, because you are lukewarm, neither hot nor cold, I will spit you out of my mouth… Be earnest, therefore, and repent. (Rev, 3:15ff.).

The focus here is on conversion from being mediocre and lukewarm. In the history of Christian holiness, the best-known example of the first kind of conversion, from sin to grace, is provided by Saint Augustine; the most instructive example of the second type of conversion, from being lukewarm to being fervent, is provided by St Teresa of Ávila. What she says of herself in her Life is surely exaggerated and dictated by the delicate nature of her conscience, but, in any case, it may help all of us to make a useful examination of our own conscience:

I began, then, to indulge in one pastime after another, in one vanity after another

and in one occasion of sin after another. Into so many and such grave occasions of

sin did I fall, and so far was my soul led astray by all these vanities […]. All the things of God gave me great pleasure, yet I was tied and bound to

those of the world. It seemed as if I wanted to reconcile these two contradictory

things, so completely opposed to one another – the life of the spirit and the

pleasures and joys and pastimes of the senses.

This state of things resulted in deep unhappiness:

I spent nearly twenty years on that stormy sea, often falling in this way and each

time rising again, but to little purpose, as I would only fall once more. My life was so far from perfection that I took hardly any notice of venial sins; as to mortal sins, although afraid of them, I was not so much so as I ought to have been; for I did not keep free from the danger of falling into them. I can testify that this is one of the most grievous kinds of life which I think can be imagined, for I had neither any joy in God nor any pleasure in the world. When I was in the midst of worldly pleasures, I was distressed by the remembrance of what I owed to God; when I was with God, I grew restless because of worldly affections.[2].

Many people could find in this analysis the real reason for their dissatisfaction and unhappiness. Let us then dwell on turning from being lukewarm. Saint Paul urged Christians in Rome with the words: ‘Do not grow slack in zeal, be fervent in Spirit’ (Rom 12:11). One would be tempted to object: ‘Well, dear Paul, that’s exactly where the problem lies! How do you turn from lukewarm to fervent if that is what you have unfortunately slipped into?” We may slip into being lukewarm, as we may fall into quicksand, but we cannot pull ourselves out by ourselves, by dragging ourselves by the hair as it were.

The objection we raise results from neglecting or misinterpreting the additional words “in Spirit” (en pneumati) which the Apostle appends to his exhortation: ‘Be fervent.’ In Paul the word ‘Spirit’ almost invariably –and certainly in this case – indicates or includes a reference to the Holy Spirit. It hardly ever exclusively refers to our own spirit or will, except in 1 Thessalonians 5:23, where it is a component of the human being, along with body and soul.

We are the heirs of a spirituality that typically saw progress to perfection as divided into three classic stages: via purgativa, via illuminativa, and via unitiva. Purification, illumination, union. In other words, we need to practice renunciation and mortification at length before we can experience fervor. All this is based on great wisdom and on centuries of experience and it would be wrong to think it is outmoded by now. No, it is not outmoded, but it is not the only way God’s grace chooses to follow.

Such a stern distinction shows a slow gradual shift from divine grace to human efforts. According to the New Testament, it is a circular and simultaneous process, whereby mortification is surely necessary to achieve the fervor of the Spirit, but at the same time it is also true that the fervor of the Spirit is necessary to be able to practice mortification. Embarking on an ascetic journey without a strong starting push by the Spirit would be dead toil and would not generate anything but ‘pride of the flesh.’ We are granted the Spirit to be able to mortify ourselves, rather than as a prize for mortifying ourselves. St. Paul has written, “If by the Spirit you put to death the deeds of the body, you will live” (Rom 8:13).

This second way, going from fervor to asceticism and to the practice of virtue, was the one Jesus wanted the apostles to follow. As the great Byzantine theologian, Cabasilas put it,

The apostles and fathers of our faith had the advantage of being instructed in every doctrine and what’s more by the Savior in person. […] Yet, despite having known all this, until they were baptized [at Pentecost, with the Spirit], they did not exhibit anything new, noble, spiritual, better than in the old times. But when baptism came for them and the Paraclete stormed their souls, then they became new and they embraced a new life, they were leaders for others and made the flame of the love for Christ shine within themselves and others. […] In the same way, God leads to perfection all the saints who have come after them.[3]

The Fathers of the Church expressed all this with the attractive image of ‘sober drunkenness’. What drove many of them to take up from Philo of Alexandria[4] this paradoxical statement, or oxymoron, were Paul’s words to the Ephesians:

Do not get drunk on wine, in which lies debauchery, but be filled with the Spirit, addressing one another [in] psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and playing to the Lord in your hearts, giving thanks always and for everything in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ to God the Father” (Eph 5:18-19).

Starting with Origen, countless texts of the Fathers spelled out this image, by playing either on the analogy or on the contrast between physical and spiritual drunkenness. Those who, at Pentecost, mistook the apostles for drunkards were right – as Saint Cyril of Jerusalem writes -; their only mistake was to relate that drunkenness to ordinary wine, whereas it was ‘new wine,’ made from the ‘true vine’ which is Christ; the apostles were indeed drunk, but theirs was a sober drunkenness crushing their sins and reviving their hearts[5].

How can we take up this ideal of sober drunkenness and embody it in the present situation in history and in the Church? Why should we take it for granted that such a strong way of experiencing the Spirit was an exclusive privilege of the Fathers and of the early history of the Church, but that it is no longer the case for us? Christ’s gift is not limited to a specific age, but it is offered to every age. It is precisely the role of the Spirit to make Christ’s redemption universal and available to anyone, at any point in time and space.

As an early Father put it, a Christian life filled with ascetic efforts and mortification, but short of the enlivening touch of the Spirit, would look like a Mass service with many readings, rituals, and offerings, but without the priest consecrating the species. All would remain what it was before, bread and wine. As the Church Father concluded,

The same also applies to Christians. Even if they have perfectly fasted, taken part in the vigil, sung the psalms, performed every ascetic deed, and practiced virtue, but grace has not worked the mystical operation of the Spirit on the altar of their hearts, that whole ascetic process is incomplete and almost vain, because they are not filled with the joy of the Spirit mystically working in their hearts’ [6]

What are the ‘places’ where the Spirit acts today in the same way as it acted at Pentecost? Let us listen to Saint Ambrose who, among the Latin Fathers, was the herald par excellence of the sober drunkenness (sobria ebrietas) of the Spirit. After mentioning the two classic ‘places’ – the Eucharist and Scriptures – where the Spirit can be drawn from, he hints at a third option, saying:

There is also another drunkenness caused by the drenching rain of the Holy Spirit. In the same way, in the Acts of the Apostles, those who talked in different languages appeared to their listeners to be filled with wine.[7]

After mentioning the ‘ordinary’ means, with these words saint Ambrose hints at a third ‘extraordinary’ one, by which he means something that is not pre-planned, nor is it something institutional. It is about reliving the experience of the apostles on the day of Pentecost. Certainly, Ambrose did not intend to point to this third option, to say to his listeners that it was not accessible to them, being exclusively reserved to the apostles and to the first generation of Christians. On the contrary, he wants to spur his congregation to experience that ‘drenching rain of the Spirit” which took place at Pentecost. That is what Saint John XXIII meant to do with the Second Vatican Council: a ‘new Pentecost’ for the Church.

Therefore, we also have a chance to draw the Spirit from this channel, solely dependent on God’s own free and sovereign action. One of the ways the Spirit is made visible in this manner outside the institutional channels is the so-called ‘baptism in the Spirit.’ I only hint at it in this context without any intended proselytism, but only in response to Pope Francis’ frequent exhortation to Catholic Charismatic Renewal members to share the ‘current of grace’ experienced in the baptism of the Spirit with the whole people of God.

The phrase ‘Baptism in the Spirit’ comes from Jesus himself. On referring to the approaching Pentecost, before ascending to heaven he said to his apostles: ‘John baptized with water, but in a few days you will be baptized with the holy Spirit” (Acts 1:5). That ritual has nothing exoteric; rather, it consists of extremely simple, calm and joyful gestures, along with feelings of humility, repentance and willingness to become like children.

It is a renewal with fresh awareness not only of Baptism and Confirmation but also of the entire Christian life, of the sacrament of marriage for married people, of their ordination for priests, of their religious profession for consecrated people. The candidate prepares for the baptism in the Spirit not only with a good confession but also by participating in instruction meetings, where they can come into living and joyful contact with the main truths and realities of faith: God’s love, sin, salvation, the new life and transformation in Christ, charisms, the fruits of the Spirit. The most frequent important fruit is the discovery of what it means to have a ‘personal relationship’ with Jesus risen and alive. In the Catholic understanding, the Baptism in the Spirit is not the end of a journey, but a starting point to mature as Christians and as committed members of the Church.

Is it right to expect everyone to go through this experience? Is it the only way of experiencing the grace of the renewed Pentecost hoped for by the Second Vatican Council? If by baptism in the Spirit we mean a certain ritual, in a certain context, the answer must be no; it is certainly not the only way of enjoying a strong experience of the Spirit. There have been and there are countless Christians who have had a similar experience, without being aware of the baptism in the Spirit, and received a clear increase in grace and a new anointment with the Spirit after a retreat, a meeting or thanks to something they have read. Even a course of spiritual exercises may very well end with a special invocation of the Holy Spirit if the leader has had that experience and participants welcome it. If someone doesn’t like the expression “baptism of the Spirit”, let him or her leave it aside and instead of the “baptism of the Spirit” ask for the “Spirit of the baptism”, that is a renewal of the gift received in the baptism.

The secret is to say ‘Come, Holy Spirit’, but to say it with your whole heart, knowing that such invitation will not remain unheard. To say it with an “expectant faith”, leaving the Spirit free to come in the way and with the manifestations he decides, not in the way we think he should come and manifest himself.

The ‘baptism in the Spirit’ has turned out to be a simple and powerful means to renew the life of millions of believers in almost all Christian Churches. Countless people, who were Christians only by name, thanks to that experience have become real Christians, engaged in prayer of praise and in the sacraments, active evangelizers, willing to take on pastoral tasks in their parishes. A true conversion from being lukewarm to being fervent! We should really say to ourselves what Augustine used to repeat, almost with indignation, to himself when he heard stories of men and women who, at some point, left the world to devote themselves to God: “Si isti et istae, cur non ego?”[8]: ‘If those men and women did, why don’t I do too?’

Let us ask the Mother of God to obtain us the grace she obtained from her Son at Cana of Galilee. Through her prayer, on that occasion, water turned into wine. Let us ask that through her intercession the water of our own lukewarmness may be turned into the wine of renewed fervor. The same wine that in the apostles at Pentecost caused the sober drunkenness and made them ‘fervent in the Spirit.’

Translated from Italian by Paolo Zanna

[1] S. Tommaso, S.Th, I-IIae, q. 113, a. 4.

[2] St Teresa of Ávila, The Life of Teresa of Jesus, chs. 7-8; http://www.carmelitemonks.org/Vocation/teresa_life.pdf.

[3] N. Cabasilas, Life in Christ, II, 8: PG 150, 552 s.

[4] Philo of Alexandria, Legum allegoriae, I, 84 (methē nefalios).

[5] St Cyril of Jerusalem, Cat. XVII, 18-19 (PG 33, 989).

[6] Macarius the Egyptian, in Filocalia, 3, Torino 1985, p. 325).

[7] St Ambrose, Comm. on Ps. 35, 19.

[8] St Augustine, Confessions, VIII, 8, 19.