Thinking, rethinking, weighing, acting

A reflection on human dignity, responsibility and sustainability in ‘Elogio del pensar’ by Ricardo Piñero Moral

Getting up every morning and setting a purpose for the day is to go through life with a direction: an origin, a destination, a task. Ricardo Piñero Moral’s book, Elogio del pensar. Una cuestión de Principios (Palabra, 2023) is an encouraging read that clarifies the principles that help to better understand the various dimensions of the human condition. The dignity of the person is the cornerstone on which a good life in society is built. Every one of us is connected in a social fabric in which the various biographies are intertwined. It is good for us to be in company, living together, in such a way that our environment becomes a home, a common house: “being cared for and caring, being aware of the needs of those around us, feeling the presence and affection of our loved ones” (p. 44). Aspirations are inherent to our relational nature. A common home built, often in fits and starts, improved in small doses, not exempt from setbacks or scares.

We want the good of our fellow men and we adopt an attitude of benevolence towards our neighbours. But living in society leads us to take a step further: charity. That is, not only wanting the good of others but also being willing to do good to those near and far, seeking progress for them, deployed in small and real advances, within reach of everyday life. The good of our neighbour is not alien to us. Hence, the author reminds us that “either we seek development for all men or that will not be development. Either we seek development for all men, or that will not be development. What we call development can only be so if it is integral, quantitatively and qualitatively.” Saint Paul VI, in his encyclical Populorum progressio (1967), referred to progress in these same terms.

Progress leads us by the hand to another concept, that of sustainability, by which every undertaking must try to endure over time, dialoguing healthily with the environment and with all the stakeholders involved. Piñero’s proposal seems challenging to me and breaks the barriers of certain proposals that understand sustainability only in terms of operating ecosystems. Piñero, rather, opts for a philosophy of sustainability that houses a philosophy of responsibility, because “responsibility is not an abstract, it requires a subject, you and me that carries out an act and freely and voluntarily assumes that what it does is done for a reason, and if the reason is very good, even better (…). There is nothing more concrete than being alive and wanting to continue being so” (p. 83). Personal responsibility and systemic sustainability go hand in hand.

Piñero adds another principle for the good life, perfectibility, that is, trying to develop the best version of oneself in order to reach the common good. The author’s precisions are enlightening. He maintains that “the common good is the set of conditions of social life that make it possible for each one of us to fully achieve our own perfection. The common good is not about having, it is about being (…). The common good is about making us who we are called to be” (p. 95). We are all called to contribute to this life in common that has given us so much, we are debtors from the beginning of life, and we must continue this chain of life by contributing our talents to generate better conditions for the flourishing of people.

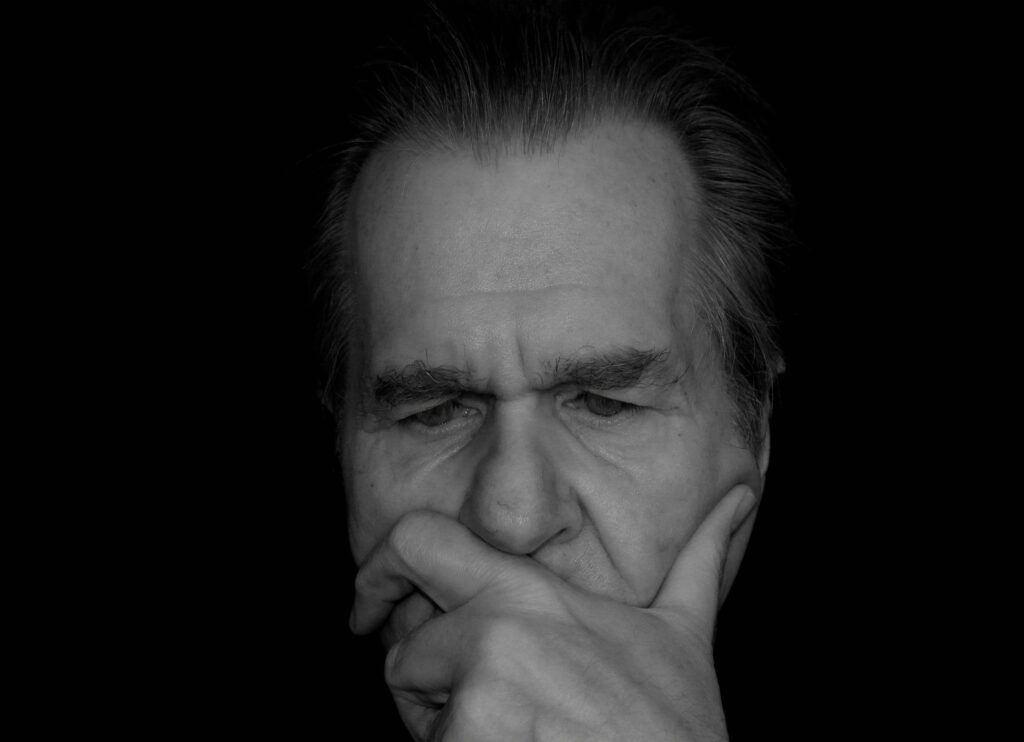

The painting that illustrates the cover of the book speaks for itself. It is Saint John the Baptist in meditation by Bosco (h. 1489). The disturbing motifs of the painting contrast strongly with the little lamb crouching on a ledge of the ground: innocence and vulnerability capable of changing the world.

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)