The wounds of the Holocaust and faceless capitalism that encourage hatred of foreigners

“The Brutalist”

The film “The Brutalist” investigates the original sin of the growing expressions of racism, genocide and objectification of the person that corrode humanity. The director, Brady Corbet, through the fictional odyssey of an architect who survives the Holocaust, shows how faceless capitalism replicates evils embedded by the Nazi horror that, today, are perpetuated in liberal democracies that encourage hatred of foreigners. The film draws a beautiful metaphor with the humanizing function of art, through brutalism, a version of radical honesty in architecture.

The famous Goethe quote, read by a voice-over: “No one is as much a slave as he who believes himself free without being so,” prepares the viewer, in absolute darkness, for a film, The Brutalist, which for almost four hours of footage – with an innovative fifteen-minute interlude – dazzles, disturbs and prevents one from taking one’s eyes off the big screen. The film begins with the arrival in the United States of Lászlo Tóth (Adrien Brody), a Holocaust survivor, whose life plans and promising career as an architect in Budapest are twisted by the Nazi occupation of Hungary. Lászlo suffers the horrors of the Buchenwald extermination camp and the forced separation of his family because his wife, Erzsébet (Felicity Jones), and his niece, Szofia (Raffey Cassidy), are interned in a different camp, Dachau. They have also managed to survive, although with serious after-effects, which the protagonist is initially unaware of. On the other hand, legal restrictions on migration force Erzsébet and Szofia to remain in Europe and to trust in a reunion that will take four years to come to fruition. In the first part of the film, under the title “The Enigma of Arrival,” Europe is the great ellipsis, representing the hidden and the murky that the protagonist avoids facing. Perhaps for this reason, Erzsébet and Szofia only exist in Lászlo’s memory and in the letters that, later on, they begin to exchange when they find out that everyone is still alive.

The images that capture Lászlo’s arrival in the host country are wrapped in a symbolism that shocks because of what they show and what they hide. The striking inverted photograph of the American totem, the Statue of Liberty, is a premonition of the protagonist’s difficult struggle to recover his identity and fight the stigma of the atrocities committed in the Shoah[1].

From this moment on, the director draws a line of continuity between the evils embedded in Nazi horror and those of faceless capitalism that cast their shadow, today, in hatred of foreigners. Brady Corbet visualizes the rottenness hidden in the myth of the “American dream” and the false rhetoric of being a land of second chances, from the portrait of the suffering and the feeling of helplessness of Lászlo when he tries to make a place for himself in American society. He is forced to face a time of poverty and misery in which he has to live as he did not expect, as a vagabond, frequenting the hunger queues in soup kitchens, sleeping in shelters and with no other alternative than succumbing to exploitation in risky and poorly paid jobs that no one wants to do.

From fascism to devouring capitalism

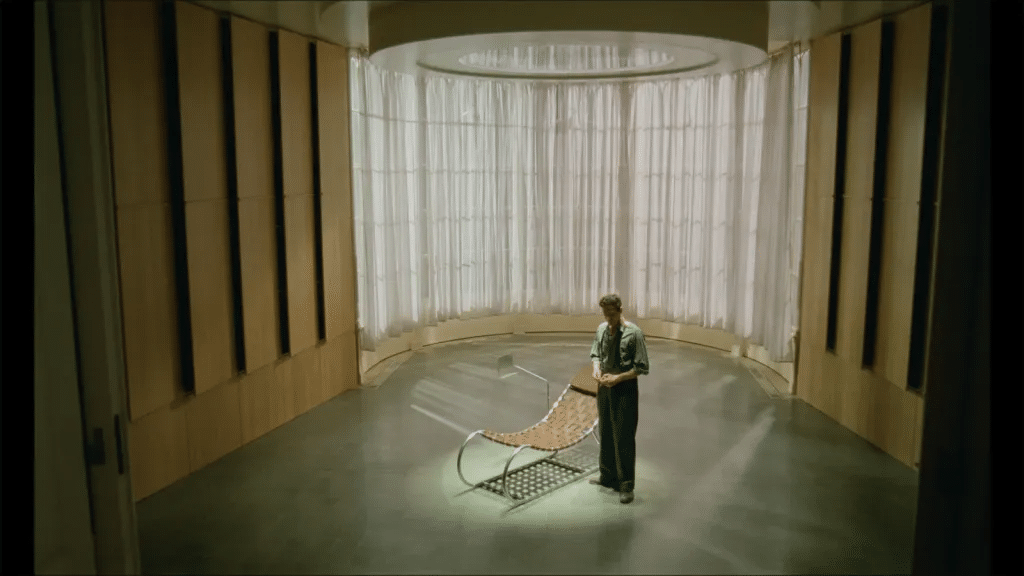

The appearance of an eccentric millionaire, Harrison Lee Van Buren (Guy Pearce), who fortuitously discovers Lászlo’s worth and investigates the popularity and scope of his architectural works in Budapest, is a turning point in the life of the protagonist. Although, not exactly for the better. The mysterious businessman, who represents the most abject of American society, frivolity and opulence, erected into a way of life, makes a commission to the architect as monumental as it is poisoned. An initial phase of forced kindness to convince the artist to accept his commission with promises that will never be fulfilled, is followed by the continuous racist disqualifications towards Lászlo by the magnate Lee Van Buren and his son Harry (Joe Alwyn) who copies the crude forms of his father. Thus, both go from being the main supporters of the visionary architect among a select group of rich and powerful people to behaving like authentic tyrants. One of the most shocking scenes of objectification of the person, starring the wealthy client, takes place during the trip with the architect to the Carrara marble quarries to choose some materials for the work.

The master-slave dynamic is embodied in a dehumanised relationship that identifies poverty with an inferior class that must be defended or that deserves to pay the consequences of negligent life decisions. “We tolerate you, don’t forget that” the magnate warns Lászlo in a violent argument. In fact, tolerating is not welcoming, but rather compromising with resentment, and this is what the architect appreciates and complains about at different moments in the film: “everyone is afraid that people like me are a danger to national security” or “they don’t want us here, we are nothing”.

The suffering increases when the millionaire uses his political influence, for an instrumental interest, and manages to get Erzsébet and Szofia into the United States. Severe osteoporosis, as a result of poor nutrition and forced labour in the Dachau extermination camp, prevents Lászlo’s wife from standing. Erzsébet, a brilliant journalist specialising in international political relations, arrives in a wheelchair and her husband has difficulty recognising her when she gets off the train in Pennsylvania. The horror of the Nazis has also taken a serious toll on Szofia, her young niece, who has been left mute by the humiliation and torture. The two realise, almost immediately, that they have escaped the clutches of Nazism to fall under the domination of a social class that looks at foreigners with hatred and distrust, rather than as a mirror that facilitates welcome. “You talk like a shoe-shine boy” or “the worst thing about our cities is that they are filling up with beggars” are some of the many boastful comments that hurt Erzsébet. However, the weakness of her bones contrasts with her empowerment and intelligence in confronting Harrison’s absurdities and outbursts of pride and, at the same time, making her husband aware of the impossibility of starting over in such an adverse context. “Promise me that you won’t let me drive you crazy (…) Don’t forget that the damage we have has been done to our bodies, but we are still the same people,” the wife warns Lászlo.

The healing power of art

In the transition from darkness to light that the protagonist travels through, the humanizing function of art, in this case architecture, is at the center of a beautiful metaphor. The filmmaker, Brady Corbet, is inspired by an architectural style, brutalism, that emerged in a post-war Europe in need of rebuilding its cities[2]. Lászlo Tóth designs with this aesthetic the building that the powerful businessman commissioned him to house a large library and multifunctional rooms. But the architect takes advantage of the opportunity to recreate the dimensions of the cells of the Buchenwald camp in his construction, in a constant tension between the intimacy of trauma and the need to create that runs parallel to the need to survive. Where the world and the being are fragmented, artistic creation, as a speaker for wounds, opens windows to hope and transcends pain, not to forget it, but to integrate it [3].

This is the effect that The Brutalist has on the protagonist, uniting his fragmented parts by the atrocities suffered and restoring his identity, descending —as Corbet titles the second part of the film— to “The core of beauty.” This is what Erzsébet refers to when reflecting on the fact that atrocities can damage our bodies, but none have the strength to take away the dignity that, intrinsic to the person, remains intact.

The exercise that Tóth does is to transcend time, a resilient act, with an aesthetic, the brutalist one, that deliberately rejects the embellishment of structures and values the raw beauty of construction materials. This exercise of radical honesty in architecture coincides with the invitation to sincere reflection that the director of the film calls us to. His message is that the wounds that we harbor in our soul have serious consequences in life and that, without reflection, habit or denial, condemn us to repeat history. Socrates said that a life without reflection is not worth living, knowing that it is the best way to ward off fanaticism, irrational beliefs or foolishness[4].

Ethics, history and contemporaneity

This film is cinema in a grand style, not only because of the footage, the shooting techniques or the great audiovisual power that contribute to dazzling the viewer, but because it unites ethics, history and our complex contemporaneity.

It is difficult to watch this film without the viewer being reminded of Trump’s plans to turn the Gaza Strip into a luxury tourist resort, taking away its lands and causing the forced displacement of more than two million Gazans; or the naturalized extermination of the thousands of migrants who risk their lives in dangerous journeys and find themselves in a Europe that closes the door to them, or tries to hide them, beyond the borders, in refugee camps where the tragedy for those fleeing war or poverty does not end, but becomes a hell, if possible, more deadly. Therefore, self-examination and critical attitude, as the philosopher Josep M. Esquirol points out [5], constitute the best intercultural ethics, a web of solidarity, responsibility for one’s neighbor, mercy and the meaning of life. There is no better way to pay respect to the dignity of the person, recognize the value of each human being, and assume the mysterious. Lászlo Tóth does so in his building that looks to the sky, with a dome crowned by a cross-shaped cavity, which when the sun rises is projected and shortens the distances between the earth and the sky.

Amparo Aygües – Master’s Degree in Bioethics from the Catholic University of Valencia – Member of the Bioethics Observatory – Catholic University of Valencia

***

[1] This is the Hebrew term, translated as “The Catastrophe” that alludes to the genocide of Hitler’s Germany against the Jews of Europe in World War II.

[2] Banhan, R. (1967). Brutalism in architecture. Gustavo Gili.

[3] López-Fernández, M. (2017). Accompanying through art. Cuadernos de pedagogía, no. 484, pp. 28-32 and The capacity of art to elaborate trauma. Obtained from https://www.icip.cat/perlapau/es/articulo/la-capacidad-del-arte-para-elaborar-el-trauma/

[4] Plato. (2011). Apology of Socrates. Austral.

[5] Esquirol, J.M. (2017). Oneself and the others. From existential experiences to interculturality. Herder.

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)