The richness of the Catholic liturgy

The fate of faith and of the Church is decided by the way we treat the liturgy

In just a few days during the month of August, I have been able to attend several Masses in different places and have seen how we can still enjoy the immense richness of Catholic liturgy and the well-done celebration of the Eucharist.

I would like to share this experience not as a theologian or a liturgist would do – for whose disciplinary assessment I am not qualified – but from the perspective of a simple layman who, day by day, is discovering the central value of the Holy Mass in his Christian life, who thanks the Lord for the wonderful event in which the Son of God is truly present in each Eucharist, and finally, who is moved by the beauty of the liturgy directed to praise, adore and give glory to God.

Extraordinary Liturgy of the Traditional Roman Rite Mass (Vetus Ordo)

I had long wanted to attend the traditional Roman Rite Mass (Vetus Ordo) which is still celebrated uninterruptedly every Sunday in the Chapel of Our Lady of Mercy and Saint Peter the Apostle in Barcelona.

In this small chapel located on Laforja Street in Barcelona, the Mass is celebrated exclusively in the extraordinary form of the Roman rite, usually sung on Sundays at noon and recited on Wednesday afternoons.

The beauty of Latin and Gregorian chants, the celebration facing God (not with our backs to the people), the mystery, the adoration, the incense, the cross and the silence in many parts of the liturgy, elevate the soul and spirit towards Heaven, while spiritually awakening all the senses of our body.

It is not surprising, then, that Pope Benedict XVI, constantly concerned that the Church of Christ should offer to the Divine Majesty a worship worthy of “praise and glory to his name,” established the following in 2007 through the motu proprio Summorum Pontificum:

“Art. 1.- The Roman Missal promulgated by Paul VI is the ordinary expression of the “Lex orandi” (“Law of prayer”) of the Catholic Church of the Latin rite. However, the Roman Missal promulgated by St. Pius V, and again by Blessed John XXIII, must be considered as an extraordinary expression of the same “Lex orandi” and enjoy the respect due to its venerable and ancient use. These two expressions of the “Lex orandi” of the Church in no way induce a division of the “Lex credendi” (“Law of faith”) of the Church; in fact, they are two uses of the one Roman rite.

It is therefore lawful to celebrate the Sacrifice of the Mass according to the typical edition of the Roman Missal promulgated by Blessed John XXIII in 1962, which has never been abrogated as the extraordinary form of the Liturgy of the Church. The conditions for the use of this missal established in the previous documents, “Quattuor abhinc annis” and “Ecclesia Dei,” will be replaced, as set out below /…/.”

According to experts and scholars on the subject, the desire for unity is what led Benedict XVI to prepare the motu proprio Summorum Pontificum on the use of the Roman liturgy prior to the reform of 1970, that is, the Missal promulgated by John XXIII in 1962, a few months before the beginning of the Second Vatican Council and which still contemplated the Mass of St. Pius V, known as the Tridentine Mass.

In another part of the aforementioned motu proprio, Pope Benedict XVI presents the following historical review that is of interest today:

“Among the pontiffs who had this concern (for the liturgy) the name of St. Gregory the Great stands out, who did everything possible to ensure that the Catholic faith as well as the treasures of worship and culture accumulated by the Romans in the preceding centuries were transmitted to the new peoples of Europe. He ordered that the form of the Sacred Liturgy relative to both the Sacrifice of the Mass and the Divine Office be defined and preserved, in the way it was celebrated in the Urbe. He promoted with the utmost attention the diffusion of monks and nuns who, acting according to the rule of St. Benedict, always together with the proclamation of the Gospel, exemplified with their lives the healthy maxim of the Rule: “Nothing should be placed before the work of God” (chap. 43). In this way, the Sacred Liturgy, celebrated according to Roman custom, not only enriched the faith and piety, but also the culture of many peoples. It is indeed a fact that the Latin liturgy of the Church in its various forms, in all the centuries of the Christian era, has inspired many saints in the spiritual life and has strengthened many peoples in the virtue of religion and has made their piety fruitful.”

It is also necessary to take into account the Instruction Universae Ecclesiae, of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, on the application of the aforementioned Motu Proprio, which in 2011 completed its reason for being.

In relation to the patrimonial and cultural value of the Catholic liturgy, in its traditional Roman rite, the letter sent in 1971 by the Primate of England, Monsignor Heenan, who also endorsed it, to Paul VI, who was surprised to see among the signatories more than eighty representatives of twentieth-century culture, is curious. Below we reproduce part of the text:

“If some senseless decree were to order the total or partial destruction of basilicas or cathedrals, it would obviously be the people who benefit from culture -whatever their personal beliefs- who would rise up in horror in opposition to such a possibility. Now, basilicas and cathedrals were built to celebrate… the Traditional Roman Mass. Yet… there is a plan to do away with this Mass… Today, as in times past, educated people… when tradition is threatened, are the first to sound the alarm. We are not considering at this moment the religious or spiritual experience of millions of individuals. The Rite in question, in its magnificent Latin text, has inspired a host of invaluable artistic achievements, not only mystical works, but those of poets, philosophers, musicians, architects, painters and sculptors of all countries and times. And so, the Rite belongs to universal culture, as much as to men of the Church and to Christians… The signatories of this completely ecumenical and apolitical petition, from every branch of European culture and elsewhere, wish to call the attention of the Holy See to the overwhelming responsibility it would incur in the history of the human spirit if it were to refuse to allow the Traditional Mass to continue.”

Among the 84 signatories were the literary figures Robert Graves, Graham Greene, Jorge Luis Borges, Cecil Day Lewis, Julien Green, François Mauriac, Eugenio Montale, Salvador de Madariaga; the philosophers Augusto Del Noce, Jacques Maritain, María Zambrano, Gabriel Marcel; the guitarist Andrés Segovia, etc.

The criticisms that were made at the time regarding the granting of free use of the Roman Missal of 1962 do not only concern the liturgical aspect, but also reveal a certain conception of the Second Vatican Council and the liturgical reform that followed, inspired by a “hermeneutics of rupture.” Pope Benedict XVI referred to this a few months after his election in his famous speech to the Roman Curia before Christmas 2005, where he called for putting aside this matrix of interpretation and adopting, instead, a constructive position based on the living Tradition of the Church, which he called “hermeneutics of continuity.”

Benedict XVI’s choice of the traditional Roman rite in its extraordinary form was not so much, as some say, a return to the past, but rather the need to fully rebalance the eternal, transcendent and heavenly aspects with the earthly and communal aspects of the liturgy. The aim was to help eventually establish a balance and harmony between the sense of the sacred and the mysterious, on the one hand, and the external gestures and attitudes and sociocultural commitments that derive from the Liturgy.

It was Saint Pius X who attributed to the liturgy the expression “primary source” of the authentic Christian spirit. The liturgy, we can say, is in the eye of the storm, because what is celebrated is what is believed and what is lived: the famous axiom “Lex orandi”, “lex credenti”.

However, as Pope Saint John Paul II stated: “European culture gives the impression of being a silent apostasy on the part of self-sufficient man who lives as if God did not exist” (Ecclesia in Europa, 9).

To delve deeper into these issues, it is recommended, among other publications, to read the book by Alberto Soria Jiménez “The principles of interpretation of the motu proprio Summorum Pontificum” (Ediciones Cristiandad, Madrid, 2014) commented by Jaime Alcalde Silva, professor at the Catholic University of Chile.

We also recommend the book “Cardinal Ferdinando Antonelli and the liturgical reform” by Nicola Giampietro (Ediciones Cristiandad, Madrid, 2005) to have a different version of the objectives initially planned and the results obtained. One day, knowing the secret diaries of Monsignor Annibale Bugnini would help us better understand what the post-conciliar liturgical reform really was.

Finally, we recommend the book “The Reform of the Roman Liturgy” by Monsignor Klaus Gamber, founder of the Liturgical Institute of Regensburg (Ediciones Buen Combate, Colección Sacerdocio y Culto, Buenos Aires, 2013). In this work, it is emphasized that it is necessary to see, in the celebration of the Holy Mass, a worship that is rendered to God, a solemn cultural action, at the center of which is God and not man.

From this perspective, the liturgy is understood above all as a sacred service performed before God; which also means, as Pope St. Gregory wrote in his “Dialogues” (IV, 60) that:

“At the hour of sacrifice, heaven opens to the voice of the priest; that in this mystery of Jesus Christ the choirs of angels are present, that which is above is joined with that which is below; that heaven and earth are united; that the visible and the invisible merge into one.”

Monsignor Klaus Gamber concludes by asking: “Why could two forms, the old and the new rite, not exist peacefully side by side? As in the East, where there are numerous rites and liturgies, and also in the West, where even today there are particular rites, as in Milan.”

However, this does not seem to be the direction that the Catholic Church has taken in these times. As is known, the motu proprio Traditionis Custodes currently governs the use of the Roman liturgy before the 1970 reform promulgated by Pope Francis in 2021.

Ordinary liturgy of the new Roman rite Mass (Novus Ordo)

Next, I would like to share my personal experience during these days of vacation with my family in different places of worship, where we attended Eucharists celebrated with rigor and devotion according to the Roman missal promulgated by Pope Paul VI (Novus Ordo).

- Mass at the Basilica of Pilar in Zaragoza.

- Mass at the Monastery of Leyre in Navarra.

- Mass at the Cathedral of Pamplona in Navarra.

- Mass at the Sanctuary of Lourdes in France.

Mass at the Basilica of Pilar

We begin our family trip, stopping as is customary on this route, at the Basilica of Pilar in Zaragoza, to honor our Mother.

The Holy Chapel of Our Lady of Pilar in Zaragoza is a baroque temple built between 1750 and 1765 inside the Basilica where the column (the “pillar”) is housed on which, according to tradition, the Virgin Mary appeared to the apostle Santiago in the year 40, and the image of the Virgin that she holds.

The space is conceived as a canopy inside the temple located under the second section of the central nave. The interior space, in the presbytery, is the Altar that prepares the priest to celebrate the mass Ad orientem, that is, facing God.

As I attended the Novus Ordo Mass in the chapel with my family that day, celebrated with all rigor and devotion by the priest, some of the reflections of Father Alberto José González Chaves came to mind, made in a series of his articles on the traditional Mass as the liturgical legacy of Benedict XVI.

Father González affirms that “in the Traditional Mass we look to the future of the Church, at the center of which is the cross of Christ, just as at the center of the altar is the High Priest, whom the Church contemplates and adores today, as yesterday and always. The gaze toward God is decisive: everything is oriented toward Him; that is why the priest looks at the cross, or the tabernacle, directed ad Dominum: ad Orientem.”

According to Father González, Benedict XVI lamented that “the priest directed toward the people gives the community the appearance of a whole closed in on itself.”

According to Father González, Benedict XVI lamented that “the priest directed toward the people gives the community the appearance of a whole closed in on itself.”

Father Gonzalez reminds us that all of Ratzinger’s small and medium-sized works on liturgical questions were collected in the Jubilee Year 2000 under the title The Spirit of the Liturgy. An Introduction, of which almost all the reviews focused on one 10-page chapter out of 250: “The Altar and the Orientation of Prayer in the Liturgy.” What Ratzinger said was, in substance, the following:

“The idea that priest and people should look at each other in prayer was born only in modern Christianity and is completely foreign to ancient Christianity. Priest and people certainly do not pray towards each other, but towards the one Lord. Therefore, during prayer they look in the same direction: either towards the East as a cosmic symbol for the coming Lord, or, where this is not possible, towards an image of Christ in the apse, towards a cross or simply towards heaven.”

According to Ratzinger, the liturgical reform has lost sight of what is at the centre: “The Cross is at the centre of the Christian liturgy, in all its seriousness: a banal optimism, which denies suffering and injustice in the world and reduces being Christian to being polite, has nothing to do with the liturgy of the Cross.” Preaching at Westminster Cathedral in 2010, Benedict XVI said that the great crucifix that dominated the nave was a reminder that Christ, “our eternal high priest, unites each day to the infinite merits of His sacrifice our own sacrifices.”

Mass at the Monastery of Leyre

We continued our family trip into Navarre towards Yesa, where we had the immense joy of attending the Novus Ordo conventual mass at the monastery of San Salvador de Leyre, inhabited by a dynamic order of Benedictine monks.

This monastery is an architectural complex in the Romanesque style, built on a natural balcony on the southern slope of the Leyre mountain range from where the valley of the Aragón river can be seen. The first kings of Pamplona rest in a pantheon of this monastery.

The motto maintained by these monks, derived from the Rule of Saint Benedict, is striking: “Nothing should come before the celebration of the Sacred Liturgy, the Work of God.”

For the monks of Leyre, “all Christian worship is paid to God through Jesus Christ, mediator between God and men. The liturgy is the main “place” of the encounter with God through Christ. The Christian liturgy is always a celebration of the mysteries of Christ, especially of his paschal mystery. In the holy liturgy, Christ makes us sharers in his life and salvation.”

His proposal to visitors and believers of our time is reflected on the monastery website in the following way: “The holy liturgy must be celebrated with a pure and humble heart and with the greatest decorum and solemnity possible. The beauty of the liturgy is an expression of the greatness, wisdom and goodness of God, a glimpse of Heaven on earth. In our monastery of Leyre we keep alive the traditional Gregorian chant, because “it is an integral part of a solemn liturgy” (Vatican II). In fact, Gregorian chant is full of artistic inspiration and religious unction. Heir to the chant of the first Christian communities, Gregorian chant will become from the 8th century onwards the musical expression of the Christian faith in the West and the most successful musical commentary on the Word of God. Given its cultural interest, it has also been declared a heritage of humanity.”

Mass at the Cathedral of Pamplona

Following the route of our family trip, we arrived at the beautiful city of Pamplona. That day, August 12, coincided with the seventh anniversary of my mother’s death and we wanted to pray for her at the Metropolitan Cathedral of Santa María la Real.

Early in the morning, we attended Lauds and then the Novus Ordo Chapter Mass celebrated entirely in Latin at the main altar of the beautiful Gothic building of the Cathedral.

Later, my children Anna and Àlex had an interesting conversation about the use of Latin in the Mass.

To reinforce my arguments, I found the reflections of Father Alberto José González Chaves very helpful. “The question is: is Latin really a hindrance? Are people really unable to understand the traditional Mass and are they able to understand the Novus Ordo? Even if we hear it in our own language, do we understand what is really happening in the Holy Mass? Has the vernacular language really helped to increase faith in transubstantiation?”

According to Father Gonzalez, “People do not understand the Mass in Latin. But neither do they understand it in the vernacular! The ‘understanding’ that many Catholics have of the Mass today is subjective and superficial, because to ‘understand’ (leaving aside the fact that it is impossible to understand the mysterium fidei) something more than the vernacular language is needed. The Novus Ordo also requires a more orthodox catechesis and a more solid preaching than is offered to the faithful today. In itself, the vernacular language does not contribute to creating a deep awareness of transubstantiation and adoration of the Blessed Sacrament.”

On the other hand, according to Father Gonzalez, the doctrinal precision of Latin preserves the orthodoxy of a liturgical text that is not subject to fashion or to temporal or sociological vicissitudes. In his monumental encyclical Mediator Dei, the Venerable Pius XII recalls that ‘the use of the Latin language… is a manifest and beautiful sign of unity, as well as an effective antidote against any corruption of doctrinal truth’. Vatican II wanted to preserve Latin in the Latin rites. On the eve of the opening of the Council, with the Apostolic Constitution Veterum Sapientia, St. John XXIII recalled that if Catholic truths were entrusted to modern languages subject to change, their meaning would not be sufficiently manifested. The Latin Mass reminds us, in addition to the primacy of the Roman Pontiff, that we belong to a universal, Catholic communion. Pope Pius XI said in his 1922 Letter Officciorum Omnium: ‘The Church, because she embraces all nations and is destined to endure to the end of time, requires, by her very nature, a language that is universal, unchanging, and not vernacular.’ And St. John Paul II wrote in 1980, in Dominicae Coenae, that ‘the Roman Church has a special debt to Latin, the splendid language of ancient Rome, and must manifest it on all occasions that present themselves.’ Even if some of the faithful (not as many as we would have you believe) are not friends of Latin, it would be completely contrary to the mind of the Church to affirm that the Mass should be celebrated entirely in the vernacular. Trent declared: ‘If anyone says… that the Mass should be celebrated only in the vernacular… let him be anathema’ (Session XXII, canon 9). It is striking that the Council makes this point with an anathema in a dogmatic canon and not in a disciplinary decree.

And yet, from all of the above, today we suffer in the Church a real damnatio of Latin, which, dragging Gregorian chant with it, has made it so that the latter is no longer heard in churches, monasteries and seminaries, but in secular concerts, turned into a vehicle for profit alien to the faith.

Although, as we have seen, there are places where the Novus Ordo Mass in Latin is wonderfully preserved, accompanied by beautiful Gregorian chants.

Mass at the Shrine of Lourdes

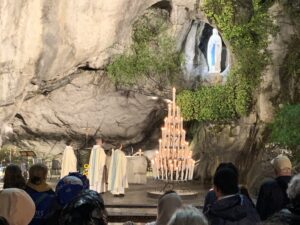

Our family trip ended with a pilgrimage to the Shrine of Our Lady of Lourdes in France, the vigil and the day – August 15 – that the Church celebrates the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary into heaven.

The Shrine complex includes the Basilicas of the Immaculate Conception, Our Lady of the Rosary and St. Pius X, as well as the Grotto of the Apparitions, where Our Lady presented herself to Bernadette Soubirous, saying that She was the Immaculate Conception.

During those days, we attended several Masses according to the Novus Ordo rite in different places of worship within the Shrine. Particularly remarkable was the solemn Mass for the feast of the Assumption celebrated on the esplanade before thousands of pilgrims, many of them from African countries and India. At that Holy Mass, Latin, French and various vernacular languages were harmoniously combined. Also worthy of note were the music, songs and hymns chosen for that occasion, which were of great beauty.

However, I would like to highlight the silence and the feeling of profound adoration that was felt in all the celebrations and events in the Shrine. I was particularly struck by the gestures and attitude of humility – kneeling before the Lord – of the pilgrims from African countries.

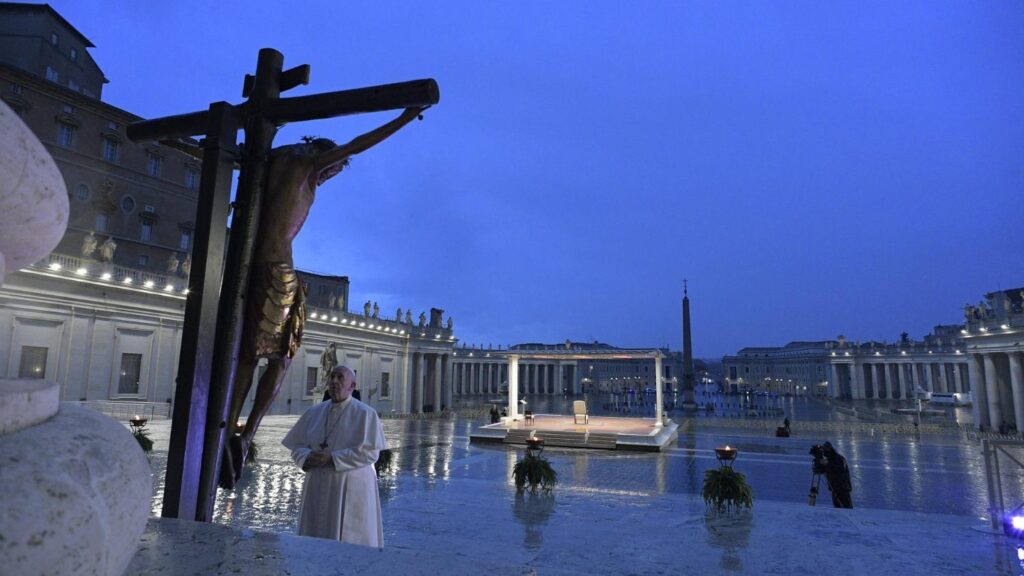

As Father Alberto José González reminds us, for Benedict XVI the relationship between the Eucharist and adoration is intrinsic, which is like the spiritual ‘environment’ within which the community can celebrate well. The liturgy must be preceded, accompanied and followed by an interior attitude of faith and adoration, because in the Eucharist, He who comes to meet us and wishes to unite with us is the Son of God, and before the crucified Christ the whole cosmos, heaven, earth and the abyss, kneels (cf. Phil 2:10-11)… The humility of God, the love to the cross, shows us Who God is. Before Him we kneel, adoring. Kneeling is no longer an expression of servitude, but rather of the freedom that God’s love gives us, the joy of being redeemed.

Hence Benedict XVI’s silent lesson on Communion given in the mouth and on one’s knees, since Communion in the hand is something permitted by an indult, that is, an act of limited duration, which, on the other hand, has become the rule, with the consequent undervaluation of the sacredness of the gesture and of the real presence itself.

Father Gonzalez continues his reflection: “There are environments, not a little influential, that try to convince us that there is no need to kneel. They say that it is a gesture that does not fit our culture (but which one does?); it is not suitable for the mature man, who goes to meet God and presents himself upright. (…) It may be that modern culture does not understand the gesture of kneeling, to the extent that it is a culture that has moved away from faith, and no longer knows the One before whom kneeling is the appropriate gesture, indeed, interiorly necessary. Whoever learns to believe, also learns to kneel. A faith or a liturgy that did not know the act of kneeling would be sick at a central point.”

Finally, Father Gonzalez indicates to us as a gesture of adoration, not only prostration: also silence. The profound silence of a million young people before the Blessed Sacrament in Cologne was unforgettable for Benedict XVI, who said: “That prayerful silence united us, it gave us great comfort. In a world where there is so much noise, so much confusion, the silent adoration of Jesus hidden in the Host is needed.” In the traditional Mass, the “silence” of the Roman Canon and the consecration reminds us that the world was silent during the crucifixion. Only the timid ringing of the bells pierces this sacrum silentium, announcing the elevation of the Host and the Chalice.

Despite the thousands of pilgrims and sick people who filled the various places in the Sanctuary of Lourdes on the day of the feast of the Assumption, the silence and the attitude of adoration were the note to be highlighted, guided by our Mother, the Blessed Virgin Mary who always shows us the right path to Jesus.

Conclusion

As Benedict XVI suggested, it is essential that in these times of loss of faith among many Catholics, the Novus Ordo be influenced by the Vetus Ordo, in that which reflects the great theological vision of the Sacrosanctum Concilium of the Second Vatican Council.

In the celebration, according to the Roman Missal promulgated by Pope Paul VI (Novus Ordo), the sacredness that attracts many – especially many young people – to the ancient or traditional usage (Vetus Ordo) can be manifested in a more intense way than has often been done until now.

According to Benedict XVI, the surest guarantee that the Mass celebrated according to the ordinary Roman rite according to the Missal of Paul VI can unite parish communities and be loved by them is to celebrate with great reverence in accordance with the prescriptions; this makes visible the spiritual richness and theological depth of this Missal. Both forms (Vetus Ordo and Novus Ordo) we receive from the Church, there should be no rejection. It would be wonderful if everyone could choose the way that best helps them to celebrate and nourish their faith. This would help to maintain the richness of the Catholic Holy Liturgy in our time as well.

As eminent theologians affirm, if the liturgy is fundamental for the life of the Church, its true renewal is necessary to renew the Church, because “the way we treat the liturgy decides the destiny of faith and of the Church”, since “behind the different ways of conceiving the liturgy there are… different ways of understanding the Church and, consequently, God and the relationship of man with Him. The subject of the liturgy is by no means marginal: here we touch the heart of the Christian faith”.

Related

Francis. The Human and Religious Imprint of a Papacy

Isabel Orellana

24 April, 2025

5 min

Cardinal Felipe Arizmendi: With the Risen Christ, There Is Hope

Felipe Arizmendi

24 April, 2025

6 min

You Didn’t Give Up

Exaudi Staff

23 April, 2025

2 min

Sing, pray, give thanks

Mar Dorrio

23 April, 2025

2 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)