The purpose is to prolong the patient’s life and obtain valuable information

First porcine liver transplant to a human being

It has been a few weeks since a 71-year-old man received a liver transplant from a genetically modified pig. This person is the fifth to receive a pig organ. Sun Beicheng, a surgeon at the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, who conducted the operation, said the patient “is doing very well.”

“This is very exciting news,” said Burcin Ekser, a transplant surgeon at the Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis. Although the surgeons have not transmitted the characteristics of the intervention, there is optimism among researchers due to the supposedly successful result.

At the beginning of 2022, kidney, thymus and pig heart transplants have been carried out on 4 people. As they were individuals with poor health and, for that reason, could have been candidates to receive this type of xenotransplantation (from animal to human), the cause of their death could not be well determined a few months after receiving the porcine organs. However, there is still one person alive who received an organ in mid-April.

The interesting thing is that xenotransplants have allowed researchers to obtain valuable information and they trust that, later on, it will be possible to have a source of organs to care for so many people who hope to receive them in order to survive.

It should be noted that, this year, liver xenotransplants have increased. In January, in the United States, a group of researchers connected a liver from a genetically modified pig to a person’s corpse. Later, in March, Kefeng Dou and his team at the Xijing Hospital of the Air Force Medical University in Xi’an, according to the family, transplanted a corpse from a person declared clinically dead ten days earlier, a genetically modified porcine liver: there were no signs of rejection. Later in May, another group in China transplanted a porcine liver and kidney into a human corpse.

Returning to the most recent transplant case, the person who received it had a large tumor in the right lobe of the liver, but the rest of the body had not been affected. As it was found that his liver was functioning quite poorly and the left lobe was not enough to keep him alive, it was determined that he was not a possible candidate to receive a human liver transplant. For this reason, the corresponding Ethics Committee approved the possibility, given the family’s interest, of resorting to a xenotransplantation, qualifying it as compassionate use.

On May 17, the team of surgeons removed the right lobe of the liver and replaced it with the liver of a small pig. The organ weighed 514 grams and the animal 32 kg. This pig had undergone 10 modifications in its genome that allowed it to avoid rejection of its organs, declares Hong-Jiang Wei, from the Yunnan Agricultural University in Kunming, who with his collaborators produced the animal. The modifications consisted of the introduction of seven genes that express human proteins and the deactivation of three genes that collaborate in the production of carbohydrates on the outside of porcine cells, which attacks the human immune system.

The main surgeon stated that they did not detect the presence of porcine cytomegalovirus in the pig liver, which is apparently why the person who received a porcine heart could have died two months after the xenotransplantation.

Sun Beicheng stated that the liver, after transplantation, “has normal liver function.” As soon as blood flow was restored, the organ began producing bile and went from 10 milliliters to 200 to 300 ml after thirteen days. Usually, a person in good health secretes at least 400 ml. Another aspect to consider is that Sun has not observed signs of rejection, even after the biopsy he performed on day twelve. For this reason, Jay Fishman, an infectious disease specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, asserts that the result is very positive: “In general, you don’t see those types of good signs if the organ suffers rejection,” he says. However, he indicates that indicators of chronic rejection could emerge later, although he also states that livers produce less rejection than a heart or kidney.

According to Sun, pig liver, in addition to bile, produces porcine coagulation factors and albumin. And David Cooper, a xenotransplant immunologist at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, comments that “we can learn a lot” from how these proteins work. For this reason, porcine genes could be modified to obtain human proteins in upcoming xenotransplants, if porcine proteins did not meet the needs of the person receiving the organ.

Although no signs of liver growth had been detected until day 10, Sun and his collaborators remain optimistic, considering that the liver xenotransplantation constitutes a bridge, as long as the person’s left lobe manages to grow enough to allow the organ to reach its normal function.

From an ethical perspective, the challenge facing these experiments focuses primarily on ensuring the integrity of the process and balancing risks with potential benefits. It is essential to consider the possible side effects derived from the use of genetically modified organs, especially when they come from animals, as this carries the risk of triggering zoonoses. For example, in the case of pigs, there is the possibility of transmitting retroviruses, which are present in all their genomes.

We are not discussing here human-animal chimeras, which involve the insertion of human pluripotent cells into animal embryos, and which pose the risk of migration of these cells to the brain or reproductive organs, which represents a serious ethical dilemma. However, even in the field of xenotransplantation research, aimed at addressing the shortage of organs (a very laudable goal), it is crucial to exercise the virtue of prudence and carefully evaluate the dangers involved so as not to exceed reasonable limits. Biomedical science does not benefit from research that transgresses ethical standards, but rather progresses hand in hand with respect for human dignity.

Related

His Hope Does Not Die!

Mario J. Paredes

24 April, 2025

6 min

The Religious Writer with a Fighting Heart

Francisco Bobadilla

24 April, 2025

4 min

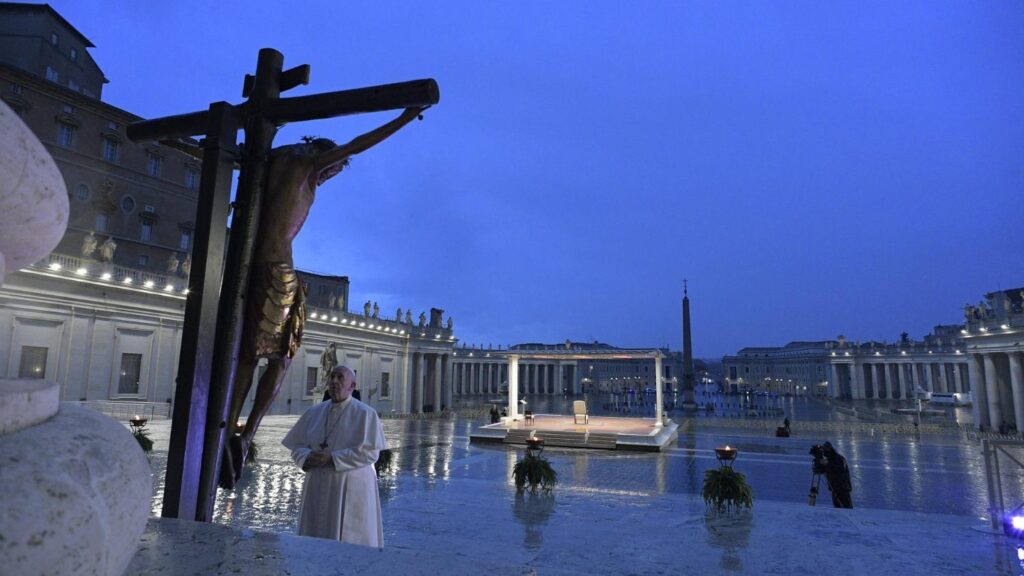

Francis. The Human and Religious Imprint of a Papacy

Isabel Orellana

24 April, 2025

5 min

Cardinal Felipe Arizmendi: With the Risen Christ, There Is Hope

Felipe Arizmendi

24 April, 2025

6 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)