The Living Man and the Virtues

Chapter 6 of the “Soul-body” Series

In this chapter, we will briefly discuss the virtues. St. Irenaeus said that “the glory of God is the living man.” What does this mean? It means that we are born men, but we must become human. We are not born full-fledged, nor do we become so by pure instinct, as happens with animals, but by choosing well. There are behaviors and actions that help us to fulfill ourselves, and others that do not.

This is not a voluntary or dogmatic question, but rather it comes from a realistic anthropology that we can all experience. Within each of us we find natural tendencies and inclinations. There are things that we like “from the factory”: pleasure, activity, recognition, relationships with others, friends, art, and transcendence, that is, having a meaning in life. Each of these tendencies is like a blind motor that seeks its object.

For example, pleasure seeks a cake if a person has a sweet tooth, or a sporty person wants to play tennis or go cycling. These tendencies must be channeled or not, since they can collide with each other. Someone must judge whether they suit us not only because of that particular tendency, but whether they suit the person as a whole.

Within each of us there should be an ultimate good, a goal in life. If we have not proposed it, we have it by osmosis. Everyone has a goal: it can be family, work, pleasure, fame, or money. The only faculty with eyes capable of saying whether these pretensions help the ultimate good or not is reason, intelligence.

When we talk about doing sports, for example, the time comes to do it and we may not feel like it, or we may. But it is reason that has to decide. Good acts are those that contribute to our ultimate good. Moral goodness or evil is not dogmatic, but what makes us what we really want. If we have a clear objective, we will know what to do at each moment, and those acts that contribute to that final end are called good.

The repetition of good acts generates habits, customs, and a facility for doing good. The person who has to support a family acquires habits; he is not lazy because he cannot afford it. These are the virtues: good, operational habits. The fulfilled man, who is the glory of God, is the virtuous man. Habits perfect the person’s tendencies and choices.

The virtue of fortitude helps us to face what is difficult, temperance helps us to be measured with what is pleasant, and justice helps us to want the good not only for ourselves but also for others. These cardinal virtues improve tendencies. Prudence improves the elective dynamic: a prudent person chooses well, an imprudent one makes mistakes.

Virtues form a second nature. We are born with human nature, but we must become human. This is an acquired nature, and depending on whether we have more or less virtues, we will be more or less fulfilled. The inner beauty of the virtues is what makes someone a “beautiful person.”

In the processes of beatification and canonization, it is studied whether the candidate has lived the virtues to a heroic degree. The virtues are fundamental for the spiritual struggle and for inner progress. We can examine our virtues and see which ones are more deeply rooted and which are more weakened.

To advance in the virtues, constancy and voluntariness are needed. The virtues are acquired by constant and voluntary repetition of acts. The particular and general examination are tools to strengthen and keep track of our virtues. The virtues are not manias, they are the muscle of love. Without them, one cannot love. So, let us cultivate the virtue that we need most.

Chapter 01: The Assumption of the Virgin and the Relationship between the Body and Grace

Chapter 02: Corporeality, Body and Grace: The Spirit Incarnated in Concrete Life

Chapter 03: Spiritual History and the Time of Life

Chapter 04: Care of the Body as a Manifestation of Spiritual Life

Chapter 05: Mortification

Related

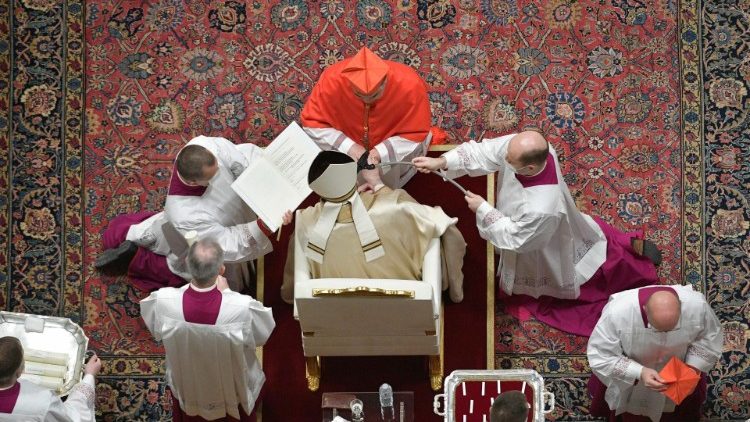

Current Status of the College of Cardinals

Exaudi Staff

23 April, 2025

14 min

The Challenges of the Next Pope and the Path of Grace

Javier Ferrer García

23 April, 2025

4 min

Pope Francis’ Spiritual Testament

Exaudi Staff

22 April, 2025

1 min

“You give us hope and remind us that God does not forget us” importa

Exaudi Staff

22 April, 2025

5 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)