The formation of character

Return to the pedagogy of effort

I remember a football match in which the first place was being decided. The 12-year-old players rushed through an exciting and intense game in order to win the victory that is elusive for one team and a crown for the other. After the match, I was struck by the marked contrast in the children’s expressions. Among the losers, sadness took over their faces, tears ran down their cheeks without shame, and their gazes fixed on the floor contained rage and frustration. The parents went out of their way to console them without success: their children, distracted, ruminated on the bitter taste of defeat. While the winners expressed radiantly – without limits or forms – their triumph. The shouts, the hugs and the intertwined jumps directed the imagination towards an unreal scenario: the final of a World Cup.

Why the unbridled reaction of those children? Is it only when they lose or win in football? What part of education do parents and teachers neglect? In the order and hierarchy of the goods to be achieved? In the formation of a weak character by dint of granting, giving, and approving without criteria or limits? School and family share stellar roles in the great task of channeling the effectiveness of children and young people.

What should schools try to avoid? Softness in teaching, which is nothing other than banishing the idea that entertainment should prevail in teaching, that the child ‘has a good time’ in the classroom. An objective that is achieved – not without exhaustion for the teacher – with multicolored images, with content that demands little intellectual work, allowing disruptions to avoid ‘bad faces’ and putting the activities to be carried out to a vote. Common sense warns us that intellectual activity – conditioned to the age of the student – is attractively demanding, requires minimum conditions for its exercise and a teaching method that stimulates it. Learning requires effort, study and constant and tenacious work. But if the student is made to believe that he can learn by overcoming these habits, frustration or anger will be incubated in him when he fails. Returning to the pedagogy of effort should be a victory that schools snatch from those who seek to thrive by training mere consumers.

For their part, what should parents avoid? Being permissive. Being clear that the child is not the one who rules the house. At most, he is indulged, he will learn that he only has rights and no duties. If he is not given limits and parents try to solve his tasks and obligations for him, how is he trained in responsibility and in honoring his commitments? If he is not taught that effort is necessary to achieve goals, he is left to his own devices when he fails. When one is permissive, the child will not be able to distinguish between good and bad: everything will have the same value. If everything is equal, how difficult it is to be able to choose. When this happens, parents are in some way responsible for this inability to decide.

Finally, both didactic softness and permissiveness at home do not promote self-control or the proper exercise of freedom. Rather, they are prone to stimulate emotional overflow in the child… whether his team wins or loses.

Related

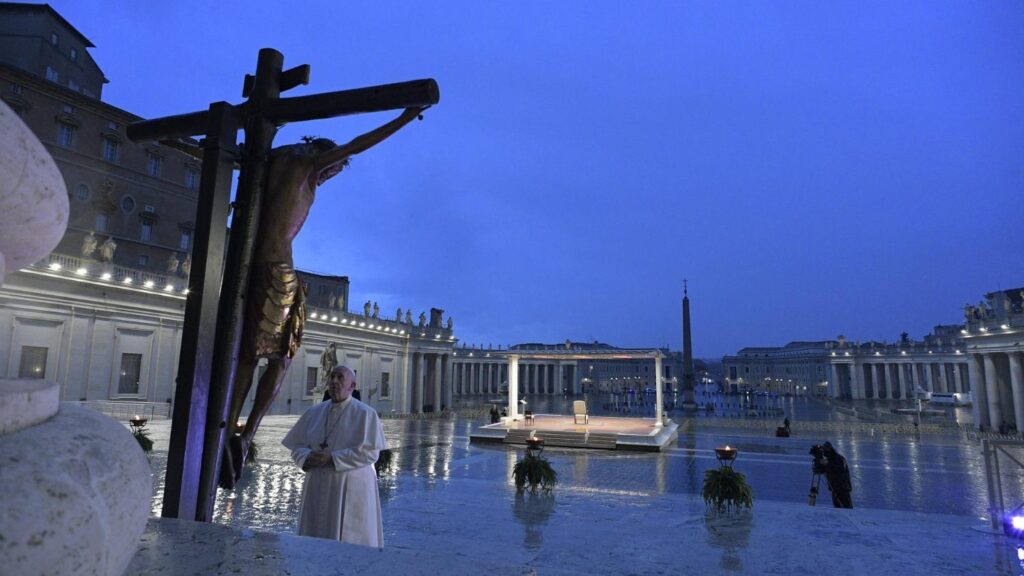

Francis. The Human and Religious Imprint of a Papacy

Isabel Orellana

24 April, 2025

5 min

Cardinal Felipe Arizmendi: With the Risen Christ, There Is Hope

Felipe Arizmendi

24 April, 2025

6 min

You Didn’t Give Up

Exaudi Staff

23 April, 2025

2 min

Sing, pray, give thanks

Mar Dorrio

23 April, 2025

2 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)