The fallacies behind the pro-abortion ideology

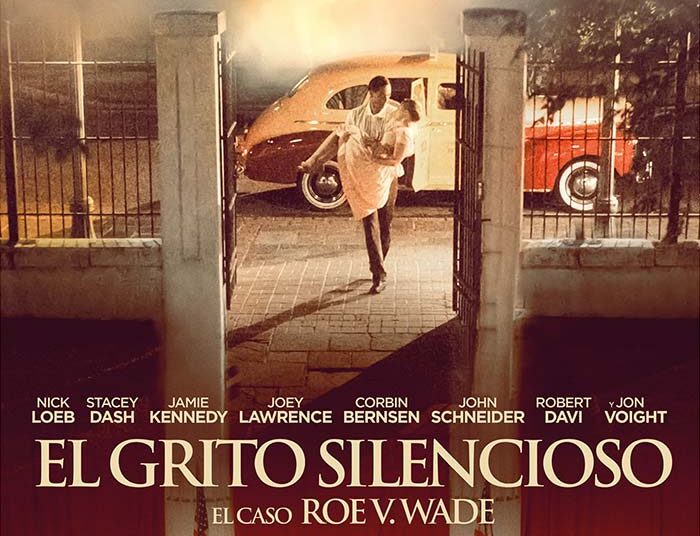

“The Silent Scream”

The intentional dissemination of false information to influence public opinion and make millions of dollars in business by hiding the truth has dramatic consequences, especially when it threatens human life and involves the sacrifice of millions of innocent people. The film “The Silent Scream” reveals the fallacious foundations, the hoaxes, the traps, and the hidden profit behind the pro-abortion ideology, starting with the Roe vs. Wade court case. This dispute heard by the Supreme Court of the United States in 1973 is at the origin of the decriminalization of abortion, its absurd consideration as a fundamental right, and the false relationship with a conquest of women’s autonomy.

In this film based on real events, the American filmmakers, Cathy Allyn and Nick Loeb, confirm the hypothesis attributed to Joseph Goebbels, head of Nazi propaganda for Adolf Hitler, that it is enough to repeat a lie for it to become the truth. This was the strategy allegedly developed by Planned Parenthood, an American organization that provides services related to reproductive technology, including induced abortion.

The film The Silent Cry: Roe vs. Wade is developed in two parallel plots. On the one hand, it tells the story of Dr. Bernard Nathanson, linked to Planned Parenthood, and responsible for more than 70,000 abortions that brought him profits of more than 20 million dollars. He denied the embryo the status of a person, argued that there was no life in conception and related his practices to gender rhetoric, appealing to the incompatibility of the criminalization of abortion with the human rights of women. Nathanson ended up converting to Catholicism, admitted that embryos are human beings in the process of development and that they experience suffering during abortion practices. In addition, he revealed the ins and outs of the Roe vs. Wade case. Wade, the hoaxes, the traps, the manipulation and the economic business driven by Planned Parenthood to influence public opinion and pressure judges of the Supreme Court of the USA. In 1973, this legal dispute was resolved with the decriminalisation of abortion and the consideration of this practice as a constitutionally protected right, related to the privacy and autonomy of women.

At the same time, the film details the case of the young Norma McCorvey, who used the pseudonym Jane Roe in her lawsuit. She lived in Texas, wanted to have an abortion and finally claimed that she had been deceived by lawyers Sarah Wessington and Linda Coffe, linked to Planned Parenthood. Both lied to Norma and took advantage of her social and economic vulnerability to involve her in the legal case and, at the same time, deploy a discursive strategy on abortion related to a gender conquest and to the mantras about privacy and the autonomy of women to decide on everything that concerns their body. In short, a private matter between the pregnant woman and the doctor.

False foundations regarding autonomy

“My body, my choice” is the slogan born around this case that, even today, is emblematic of the pro-abortion ideology. In this regard, it is argued that since abortion involves one’s own body, the decision belongs to the woman and neither the State nor society can interfere without it constituting a violation of the right to autonomy. Two other false premises are that a woman’s reproductive rights empower her to decide whether to have children, their number and the moment of conception, and the criminalization of abortion prevents this type of choice. It is also stated that since reproduction impacts on a woman’s life plan, prohibiting abortion not only forces her to continue with an unwanted pregnancy, but also prevents its free development.

The film shows how a false foundation is deliberately articulated so that society perceives it as truth and achieves certain ends. With a certain documentary feel, the filmmakers show the manipulative intricacies of the first pro-abortion social movements of the 1970s, the economic interests, the use of the media with false data, non-existent surveys, political maneuvers during the presidency of Richard Nixon and judicial pressures that benefited the Planned Parenthood empire. The first president and founder of this corporation was Margaret Sanger who in 1916 opened an illegal contraceptive and abortion clinic in a Brooklyn neighborhood to make it easier for African-American women to terminate their pregnancies. In some scenes she appears in public events in which she defended the convenience of women of this group having abortions to avoid “the proliferation of a race less intelligent and less intelligent than the white one.”

The Roe vs. Wade case Wade granted American women the absolute right to an abortion in the first three months of pregnancy, allowing only government regulations in the second trimester and prohibiting abortion in the last trimester unless medical certificates were provided proving the risk to their life or health.

In the film, Dr. Mildred Jefferson, founder of the pro-life movement, offers scientific arguments and unquestionable data clarified by genetics that unmask the pro-abortion arguments that only recognize the status of a human being after birth. In the legal battle, she argues that life begins with fertilization and that the need to develop in the mother’s womb in order to survive does not make the embryo a part of the mother or the woman’s property, nor can it be naturalized that the mother decides which life is worth living or not. From fertilization, a different reality emerges, a new human being that has its own genetic heritage, different from the parents. The woman also puts her life in danger during this process, which leads Mildred Jefferson to put the emphasis, as shown in the film, on the objectification and instrumentalization of women, the huge economic benefits and, especially, asymmetrical power relations between the mother and an embryonic human life lacking rights. “People do not humanize what they cannot see,” the doctor laments at one point in the film.

Finally, the consideration of abortion as a fundamental right implies that, in order to guarantee its fulfillment, the duty to kill is established. Hence, abortion, together with the decriminalization and practice of euthanasia, although they are presented as new rights, actually represent a threat to the defense and protection of human life and the dignity of the person, enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948). If there is no life, the other fundamental rights are meaningless. For children, the right to life is the opportunity to live their childhood, grow, develop and reach adulthood. But, for this to happen, it is essential to be born and, therefore, that the viability of the embryo ceases to be an autonomous or political criterion subject to concessions.

Bioethical assessment

From a personalist bioethics perspective, Elio Sgreccia maintains a fundamental principle applicable to human procreation, according to which, for an action to be right, it is also required that the end be right. That is, that it implies the good of the person, and that the means are equally right and consistent with the ends.

Segreccia argues that life has an unconditional value and the tendency to diminish the biological status of the embryo and refuse to consider it a human individual, except from arbitrarily determined moments, is associated with the attempt not to consider it a human person and has its roots in a hedonistic mentality and exoneration of responsibility in sexuality. At stake are the relations of harmony and balance between love and life, between freedom and responsibility, between technology and morality[1]. In short, it is about recognizing “the centrality of the human person in his reality, beyond the same conscience and the achieved expressive capacities that are concretized in the process of maturation”[2]. Spaemann contributes in a penetrating way to clarify all this by specifying that what we call a person is not the set of certain qualities, but its bearer[3]. Human life from conception has a sacred, absolute and immeasurable value and should not be exposed to political or social consensus.

Amparo Aygües – Master’s Degree in Bioethics from the Catholic University of Valencia – Member of the Bioethics Observatory – Catholic University of Valencia

***

[1] Sgreccia, E. Bioethics Manual I. Fundamentals and biomedical ethics (2012). Chapters. IX, X and XI. Edit. BAC

[2] Ibid, p.132.

[3] Spaemann, R. (2010). People. About the distinction between “something” and “someone” Ed. Eunsa.

Related

Francis. The Human and Religious Imprint of a Papacy

Isabel Orellana

24 April, 2025

5 min

Cardinal Felipe Arizmendi: With the Risen Christ, There Is Hope

Felipe Arizmendi

24 April, 2025

6 min

You Didn’t Give Up

Exaudi Staff

23 April, 2025

2 min

Sing, pray, give thanks

Mar Dorrio

23 April, 2025

2 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)