Poland: The exhibition “Do Not Breathe Too Loudly” at the Museum of Memory and Identity in Toruń

A story about the daily life of Jews hidden in Polish families' homes

When remembering the victims of the Shoah, we cannot forget the many anonymous Polish heroes who, during the hell of the German occupation in World War II, tried to protect Jews and save them from death.

In 1939 Hitler began World War II by attacking Poland; in 1941 the Germans decided to eliminate the Jews, and the following year they developed the “general plan for the extermination” of 11 million Jews in Europe. During that period, approximately 3.5 million Jews lived in occupied Poland, corresponding to almost 10% of the Polish population.

For this reason, the Germans organized the extermination camps precisely in the occupied areas of Poland, including the infamous Auschwitz camp. Although the Poles themselves were subjected to persecution, they undertook a true campaign to help the Jews, carried out by clandestine organizations and associations, including the Council for Aid to Jews known as “Żegota,” founded as early as 1942, and by people in cities and villages.

The Church was also involved, organizing material aid, hiding Jews in religious houses and monasteries, encouraging every form of help, especially through the personal example of bishops, priests, and nuns, who in those dark and inhuman times brought to life the idea of Christian love for one’s neighbor. It is important to recall a fundamental fact: the German occupiers introduced a law in Poland—unique throughout occupied Europe—that punished with death any aid given to Jews.

But even at the risk of their own lives, Poles saved many Jews. Current estimates of the number of Poles who provided refuge to Jews range from 280,000 to 360,000. These estimates are based on the number of surviving Jews, estimated at 40–50 thousand. Approximately 1,500 Poles died for having helped Jews. For this reason, Poles are the largest national group among the “Righteous Among the Nations.”

Assistance was mostly individual, provided by single individuals or families, usually in their own homes or farms. It included temporary or long-term hiding of one or more people, organizing or paying for their hiding places, escape from ghettos, and providing false identity documents, money, food, clothing, or medicine.

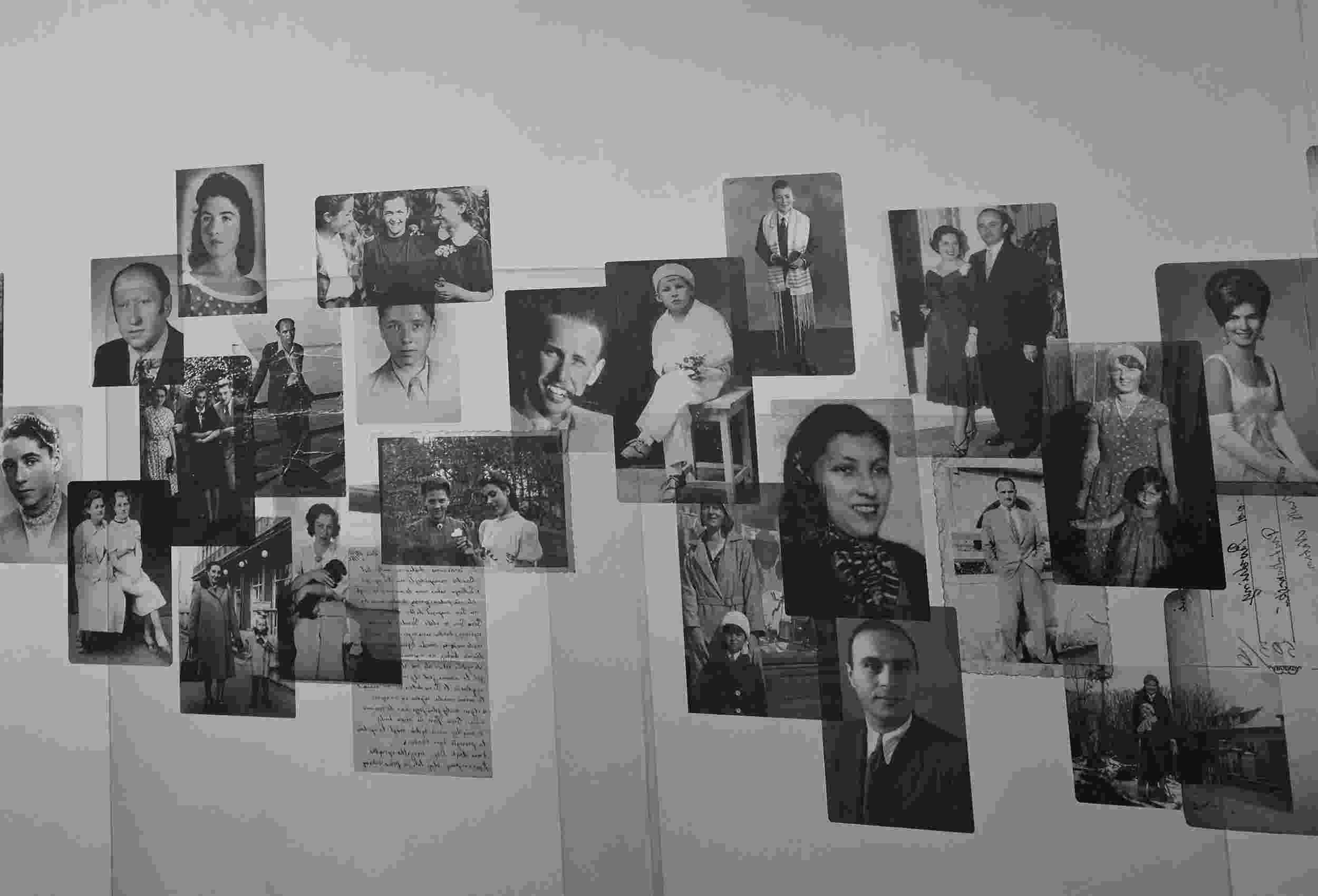

Last year in Toruń, Poland, I visited the exhibition organized at the Museum of Memory and Identity of John Paul II that recalled these almost always unknown stories, titled “Do Not Breathe Too Loudly.” It is a story about the daily life of Jews hidden in Polish families’ homes, marked by fear, the obligation of silence, uncertainty, and daily risk. The exhibition also highlighted the heroism of the Poles who risked their own lives and those of their families to help the hidden Jews. Their courage, compassion, and sense of moral duty are an extraordinary testimony of humanity in an age of contempt.

A central element of the exhibition is the portraits of those who had to learn invisibility. Their faces become a starting point for understanding the situation in which they found themselves.

The exhibition space presented hiding places, faithfully reconstructed shelters where Jews spent days, months, and sometimes years. Narrow, suffocating, and often without light, they allowed visitors to experience the difficulties of their daily existence.

The exhibition was completed by a documentary that recounted the complex context of those events: relations between Jews and Poles before and during the war, tensions, fear, but also solidarity and altruism in action. Witnesses to those events, both survivors and those who decided to help, told and shared their stories:

“Imagine a life in which you are not allowed to make any sound. Where every breath, every rustle could mean mortal danger.”

“Imagine someone who cannot be heard living under the table in your kitchen. Someone who cannot speak, move, exist. Someone who disappears to survive.”

“There were no grand gestures. There was laundry hung silently at night. There were children who had not laughed out loud for years. There was the fear of an accidental word or sound.”

The exhibition “Do Not Breathe Too Loudly” also questioned the limits of human resistance and the price of survival.

Next to the Museum of Memory and Identity of John Paul II is the Park of Memory, with illuminated glass pillars engraved with the names of the Poles who saved Jews. Meanwhile, the Sanctuary of the Virgin Mary, Star of the New Evangelization and of Saint John Paul II, located next to the museum, houses the Chapel of Memory, which commemorates in a sacred setting the Poles who died at the hands of the Germans for having saved Jews. The heroic story of each person mentioned is historically verified and documented. The Chapel and the Park of Memory have been visited several times by Israeli ambassadors in Poland.

On the Day of Remembrance, it seems appropriate to recall these places that tell the stories of the Jews who escaped extermination and of the Poles who, at the risk of their own lives, saved them.

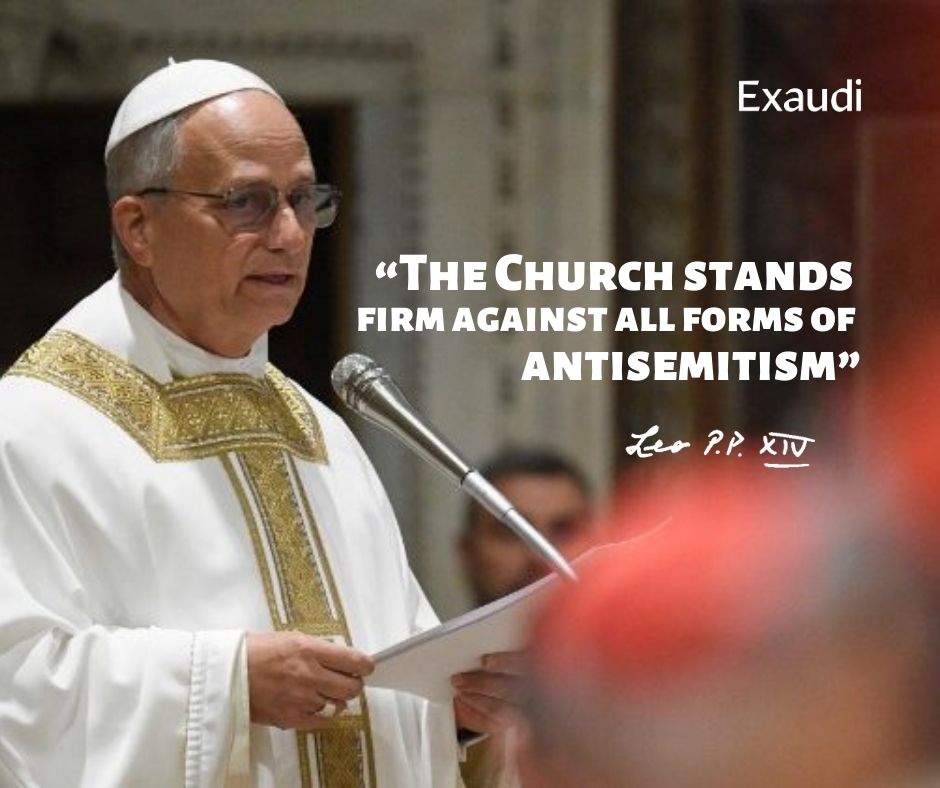

Pope Leo:

On Holocaust Remembrance Day, I would like to recall that the Church remains faithful to the unwavering position of the Declaration #NostraAetate against every form of antisemitism. The Church rejects any discrimination or harassment based on ethnicity, language, nationality, or religion.

Related

“I felt a peace that confirmed it was God calling me”

Fundación CARF

26 January, 2026

4 min

Reflection by Bishop Enrique Díaz: Those who walked in darkness have seen a great light

Enrique Díaz

25 January, 2026

6 min

The miracle of the conversion of Saint Paul

Javier Peño

25 January, 2026

4 min

Come and Follow Me: Commentary by Fr. Jorge Miró

Jorge Miró

24 January, 2026

3 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)