Salvation Promised by God not Reserved for Particular Groups

Reflection by the Chaldean Patriarch to Prepare for 'Nineveh Fast'

The salvation promised by God is not reserved for particular ethnic groups, or for certain moral categories. His mercy embraces anyone who repents and at times scandalizes those who claim to possess the gifts of grace exclusively and a priori. The reflection offered this year by the Chaldean Patriarch as an instrument to prepare for the so-called “Nineveh Fast”, which the Chaldean Church is preparing to live from Monday 7 to Wednesday 9 February, is strewn with liberating suggestions in order to enjoy the treasures of traditional pious practices, reported Fides News Agency.

In the Chaldean liturgical tradition, the so-called “Nineveh Fast” (Bautha d’Ninwaye) precedes the Lenten one by three weeks. For three days, Chaldeans who observe this spiritual practice abstain from food and drink from midnight until noon the next day, and for the duration of the fast, they avoid eating foods and condiments of animal origin.

The practice of the “Nineveh fast” refers to the fast asked by the Prophet Jonah to the inhabitants of that corrupt city, which stood in the area of present-day Mosul, a metropolis in northern Iraq that remained in the hands of the jihadists of the Islamic Caliphate (Daesh) from 2014 to 2017. That fast – so we read in the Bible – moved God (cf. Jonah 3,1) and saved the city from destruction.

In recent years, Patriarch Sako has always invited the baptized of the Chaldean Church to live the Nineveh Fast, also asking the Almighty for the gifts of peace, national harmony, and the end of the pandemic. This year, the reflection on the Nineveh Fast offered from the Iraqi cardinal contains precious philological, exegetical, and historical notes on the Book of Jonah. But the biblical text offers the patriarch above all suggestive hints to recall the traits of gratuitousness and universality that characterize the salvation promised by Christ to all peoples.

The word “Ba’utha” – Patriarch Sako recalls in his contribution, disseminated by the official media of the Patriarchate – in Syriac indicates a request and a plea. Patriarch Ezekiel (570-581) ordered a fast of penance following the spread of the plague epidemic in Mesopotamia and the death of a large number of people, to demand an end, in a similar way to what happened with the Covid-19 pandemic”.

The author of the Book of Jonah – continues the Iraqi Cardinal – wants above all to relate a new word about God, “to reveal that the salvation promised by God is for everyone and his infinite mercy embraces all those who repent”. The writer of the sacred text “sees in a sublime way the inescapable truth of God’s loving solidarity with sinners and the poor, and his desire to see them saved”.

The word “Jonah” – continues the Patriarch – in Hebrew and Syriac means ‘dove’. But the Prophet indicated by that name “is certainly not a dove of peace”: he wields the “threat of punishment” and appears closed in an intolerant religious nationalism, to the point of wanting to escape the command of God, who sends him to preach the repentance and possible salvation in a city far from Israel, to a people perceived as hostile. Jonah tries to flee in the opposite direction to that indicated by God. Then, when all the people of Nineveh repent, fast, and see the salvation promised by the Lord happen, Jonah gets angry at that gesture of divine mercy, almost reproaching God for having saved by grace an evil and enemy nation.

The position of Jonah – the Patriarch remarks – recalls that of all the rigorisms that claim to monopolize the salvation given by God for their own merit. But Jesus “came to save the world”, and the story of the Prophet Jonah shows that usually, pagans are more ready to repent and convert than those who consider themselves saved “a priori”, by condition given.

In the end, Jonah also rejoices at the change that has also taken place thanks to his preaching. Thus – adds the Patriarch – “the Book of Jonah teaches us to trust in the mercy of the Lord, to pray for others and to rejoice in their repentance, instead of grumbling”. The two positions that confront each other in the book of Jonah and throughout the history of salvation are on the one hand that of forgiveness and repentance, and on the other that of obstinacy and fanaticism. For this – Patriarch Sako points out – it is appropriate to recognize that “the message of the Book of Jonah was not addressed only to the people of ancient Nineveh, but it is a message that reaches us all, through the generations”. The Iraqi Cardinal’s reflection ends with an invitation to pray “for peace and stability in our country so that the pandemic caused by Covid-19 disappears throughout the world so that the environment is not devastated and for the unity of our Churches.

Related

“Let us pray to the Virgin to protect the Church, the Pope, this nation and the entire world”

Exaudi Staff

15 July, 2024

5 min

Spiritual closeness of Pope Francis on the occasion of the reopening of the Pontifical Representation in Honduras

Exaudi Staff

14 July, 2024

4 min

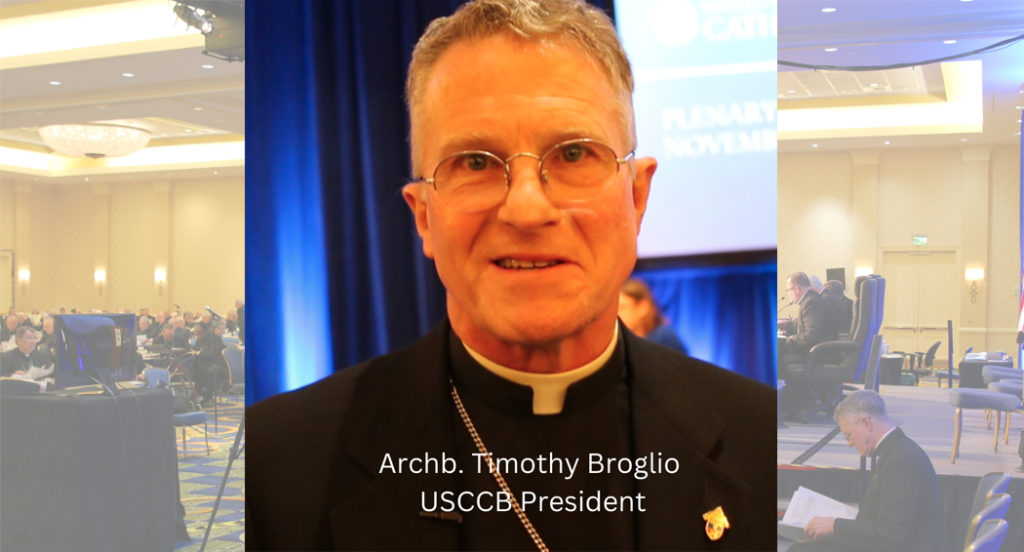

The Bishops of the United States renewed authorities: The new president is Archbishop Timothy Broglio

Enrique Soros

17 November, 2022

4 min

Iraq: Gathering the youth in hope

Ayuda a la Iglesia Necesitada

06 September, 2022

2 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)