Saint Virginia Centurione, May 21

Widow of Bracelli

Virginia Centurione was born on April 2, 1587, in Genoa (Italy).

Gaspar was a rich young man, heir to an illustrious family, but inclined to a disorderly life and the vice of gambling. From that union two girls were born: Lelia and Isabel.

Virginia’s married life did not last long. Gaspar Bracelli, despite his marriage and fatherhood, did not abandon his dissipated lifestyle, to the point of endangering his existence. Virginia, with silent patience, prayer, and kind attention, sought to convince her husband to adopt a more moderate course. Unfortunately, Gaspar fell ill, but died a Christian death on June 13, 1607, in Alessandria, assisted by his wife, who had moved there to cure him.

When she became a widow at only 20 years old, Virginia took a vow of perpetual chastity, rejecting the opportunities to remarry, as her father proposed, and lived in retirement at her mother-in-law’s house, dedicating herself to education and the administration of the property of her daughters and dedicating herself to prayer and charity.

In 1610 she felt more clearly her special vocation to “serve God in her poverty.” Although she was severely controlled by her father, and never neglecting to care for her family, she began to work for those in need. She served them directly, distributing half of her own income in alms, or through the charitable institutions of that time.

Once she had conveniently placed her daughters in marriage, Virginia devoted herself completely to the care of abandoned children, the elderly and the sick, and to the promotion of the marginalized.

The war between the Republic of Genoa and the Duke of Savoy, supported by France, spreading unemployment and hunger, induced Virginia, in the winter of 1624-1625, to welcome into its home, first about fifteen abandoned young women, and then , by increasing the number of refugees in the city, to all the poor people she could, especially women, providing in everything for their needs.

After the death of her mother-in-law, in the month of August 1625, she not only began to welcome the young women who arrived spontaneously, but she herself walked around the city, especially in the neighborhoods with the worst reputation, in search of the most needy and at risk of corruption.

To overcome the growing misery, she gave rise to the Hundred Ladies of Mercy, protectors of the Poor of Jesus Christ, an association that, in union with the local organization of the “Eight Ladies of Mercy”, had the specific task of directly verify, through home visits, the needs of the poor, especially if they were solemnly poor.

By intensifying the initiative to welcome young women, especially during the time of the plague and famine of 1629-1630, Virginia was forced to rent the empty convent of Montecalvario, where she moved on April 14. of 1631 with her hosts, whom she placed under the protection of Our Lady of the Refuge. Three years later, the Work already had three houses in which almost 300 shelters resided. For this reason, Virginia considered it appropriate to request official recognition from the Senate of the Republic, which granted it on December 13, 1635.

The hosts of Our Lady of the Refuge became for the Saint her “daughters” par excellence, with whom she shared food and clothing, taught them catechism, and trained them in work so that they could earn their own living support.

Proposing to give the work its own headquarters, after having renounced the acquisition of Montecalvario due to its too high priced, she bought two adjoining houses on the hill of Carignano, which, with the construction of a new wing and the church dedicated to Our Lady of the Refuge became the mother house of the Work.

The spirit that animated the Institution founded by Virginia Bracelli was widely present in the Rule drafted in the years 1644-1650. It establishes that all the houses constitute the only Work of Our Lady of the Refuge, under the direction and administration of the Protectors (noble laymen appointed by the Senate of the Republic); the division between “daughters” with a habit and “daughters” without a habit is reaffirmed; but all of them must live – even if they do not have vows – like the most observant nuns, in obedience and poverty, working and praying; Furthermore, they must be willing to go and serve in public hospitals, as if they were obligated by a vote.

Over time, the Work will develop in two religious Congregations: the Sisters of Our Lady of the Refuge of Mount Calvary and the Daughters of Our Lady on Mount Calvary.

After the appointment of the Protectors (July 3, 1641), who were considered the true superiors of the Work, Virginia Bracelli did not want to interfere further in the government of the house: she was subject to their will and followed their provisions, even in the acceptance of any young person in need. Virginia lived as the last of her “daughters”, dedicated to the service of the house: she went out morning and evening to beg to provide sustenance for the entire house. She was interested in everyone like a mother, especially the sick, providing them with the most humble services.

Already in previous years she had begun a healing social action, aimed at curing the roots of evil and preventing relapses: the sick and the disabled were to be admitted to centers appropriate for them; useful men had to be initiated into work; women had to exercise at the looms and in cutting and sewing; and the children had the obligation to go to school.

As activities grew and efforts redoubled, Virginia saw the number of collaborators around her decrease, especially bourgeois and aristocratic women, who feared compromising their reputation by dealing with corrupt people and following a guide who, although noble and holy, , appreciates a bit of recklessness in his undertakings.

Abandoned by the Auxiliaries, disavowed in fact by the Protectors in the government of her Work, and occupying the last place among the sisters in the house of Carignano, while her physical health rapidly weakened, Virginia seemed to find new strength in solitude moral.

On March 25, 1637, she got the Republic to take the Virgin Mary as her protector. She insistently pleaded with the Archbishop of the city for the institution of the Forty Hours, which began in Genoa towards the end of 1642, and for the preaching of the popular missions (1643). She intervened to smooth out the frequent and bloody rivalries that, for futile reasons, arose between noble families and knights. In 1647, she obtained reconciliation between the archiepiscopal Curia and the Government of the Republic, fighting each other for pure issues of prestige. Never losing sight of the most abandoned, she was always available, regardless of social rank, to anyone who came to her for help.

Enriched by the Lord with ecstasies, visions, interior locutions and other special mystical gifts, she gave her spirit to the Lord on December 15, 1651, at the age of 64. The Supreme Pontiff John Paul II proclaimed her blessed, on the occasion of her apostolic journey to Genoa, on September 22, 1985.

She was canonized on Sunday, May 18, 2003, by Pope John Paul II.

Related

“The priest finds his reason for being in the Eucharist”

Fundación CARF

01 April, 2025

5 min

Family Valued: An international appeal for the family

Exaudi Staff

01 April, 2025

2 min

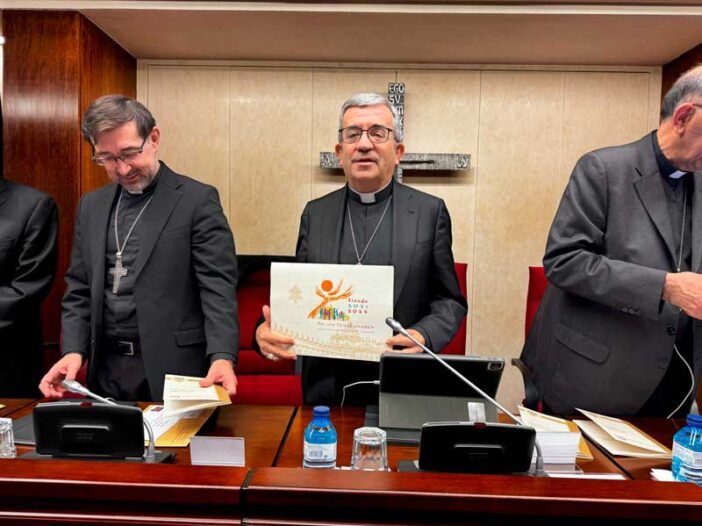

Bishop Luis Argüello Addresses the Challenges of the Church in Spain

Exaudi Staff

01 April, 2025

2 min

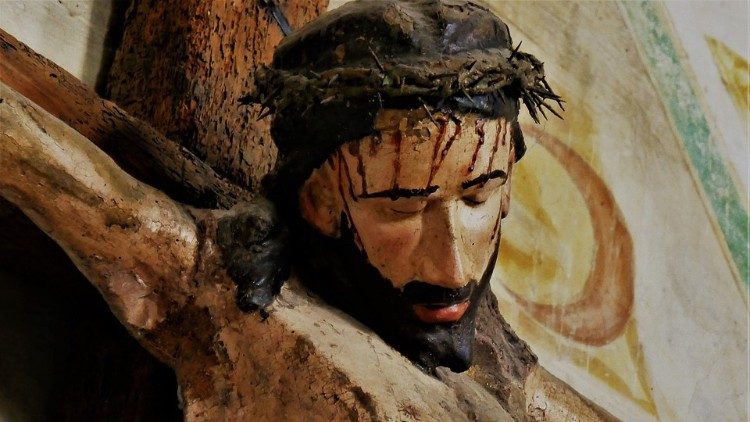

THE WAY OF THE CROSS: Accompanying Jesus on the way to the Cross

Luis Herrera Campo

31 March, 2025

5 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)