Pope: ‘This is How We Must Always Walk’

The Holy Father’s Preface to the Volume ‘Fraternity, Sign of the Times. Pope Francis’ Social Magisterium’

“This is how we must always walk: Magisterium, Theology, pastoral practice, and leadership, must always be together; fraternity will also be more credible if in the Church we ’all’ feel ourselves ‘brothers’ (Fratelli Tutti) and live our respective ministries as service to the Gospel and to the building of the Kingdom of God and the care of the Common Home,” says Pope Francis in the Prologue of a new book.

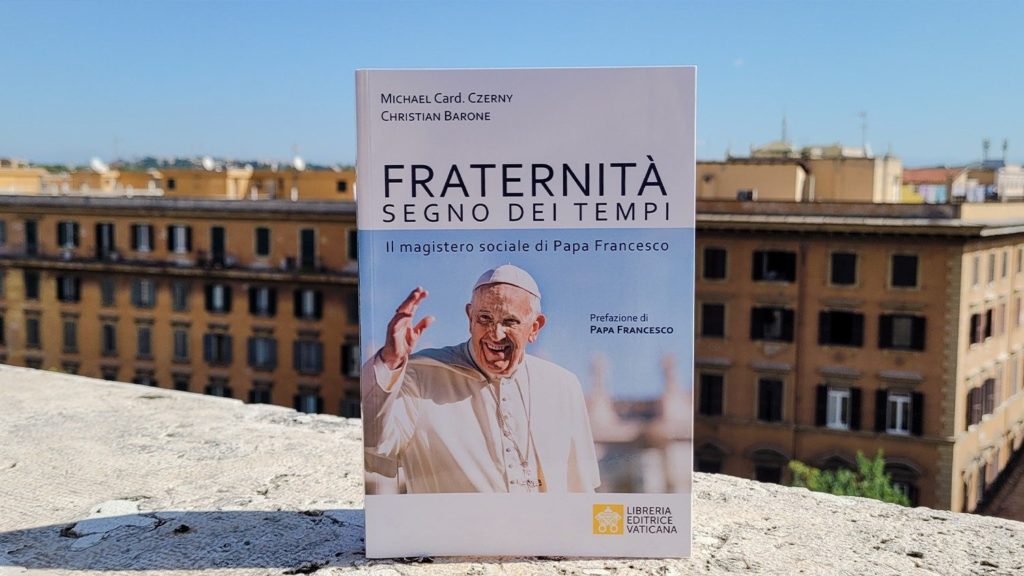

To be presented in the Vatican on September 30 is the book “Fraternity: Sign of the Times. Pope Francis’ Social Magisterium,” by Cardinal Michael Czerny and Father Christian Barone, with a Preface by the Holy Father. Intervening in the presentation will be Sister Alessandra Smerilli, interim Secretary of the Dicastery for the Service of Integral Human Development; Dr. Aboubakar Soumahoro, President of the Braccinati League and spokesman of Invisibles in Movement; and Father Armando Matteo, Deputy Under-Secretary of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. The event’s moderator will be Dr. Gerard O’Connell, correspondent of the Vatican for America.

Here is the non-official translation of Pope Francis’ Preface to the volume “Fraternity: Sign of the Times. Pope Francis’ Social Magisterium” offered by “Vatican News.”

* * *

The heart of the Gospel is the proclamation of the Kingdom of God, which is Jesus in person, the Emmanuel and God with us. In fact, in Him God realizes definitively his plan of love for humanity, establishing His lordship over creatures and introducing in human history the seed of divine life, which transforms from within.

The Kingdom of God must certainly not be identified or confused with some earthly and political conquest, but neither must it be imagined as a purely interior, personal, and spiritual reality, or as a promise that only concerns the beyond. In reality, the Christian faith lives of this fascinating and convincing “paradox,” a word much loved by Jesuit theologian Henri de Lubac: it’s what Jesus, united forever to our flesh, carries out already here and now, opening to us to a relationship with God the Father and working a continuous liberation in life and in the history we are living, because in Him the Kingdom of God has already come close (cf. Mark 1:12-15); at the same time, while we are in this flesh, the Kingdom continues to be a promise, a profound yearning that we carry inside, a cry that rises from Creation still marked by evil, which groans and suffers until the day of its full liberation (cf. Romans 8:19-24).

Hence, the Kingdom proclaimed by Jesus is a living and dynamic reality, which invites us to conversion and asks our faith to come out of the statism of an individual religiosity or one reduced to legalism, in order to be, instead, a restless and continuous search for the Lord and His Word, which every day calls us to collaborate in God’s work in the different situations of life and of society. In different ways, often silent and anonymous, often also in the history of our failures and wounds, the Kingdom of God is taking place in our hearts and in the history that surrounds us, as a small seed hidden in the earth (cf. Matthew 13:31-32), as a bit of leaven that ferments the dough (Matthew 13:24-30), Jesus introduces in our history the signs of the new life that He came to inaugurate and He asks us to collaborate with Him in this work of salvation: each one of us can contribute to carry out the work of the Kingdom of God in the world, opening areas of salvation and liberation, sowing hope, challenging the lethal logic of egoism with evangelical fraternity, committing us to tenderness and solidarity in favor of our neighbor, especially the poorest. This social dimension of the Christian faith must never be neutralized. As I also reminded in Evangelii Gaudium, the kerigma of the Christian faith has in itself a social content, which invites to build a society in which the logic of the Beatitudes and a solidary and fraternal world triumphs.

The God-Love, that in Jesus invites us to live the commandment of fraternal love, heals our inter-personal and social relations through love and calls us to be architects of peace and builders of fraternity among us: “The proposal is the Kingdom of God” (Luke 4:43); it’s about loving God who reigns in the world.

To the degree that He is able to reign among us, social life will be an area of fraternity, justice, peace, and dignity for all. Therefore, both the proclamation, as well as the Christian experience, tend to trigger social consequences” (Evangelii Gaudium, 180). In this connection, the care of our Mother Earth and the commitment to build a solidary society in which we are “all brothers,” not only are not foreign to our faith but are a concrete realization of it.

This is the foundation of the Social Doctrine of the Church. It’s not about a simple social aspect of the Christian faith, but of a reality that has a theological foundation: God’s love for humanity and His design of love and fraternity, which He carries out in history through Jesus Christ His Son, to whom believers are intimately united by the Spirit.

Therefore, I am grateful to Cardinal Michael Czerny and Father Christian Barone, brothers in the faith, for this contribution which they offer on fraternity and for these pages that, while hoping that they are an introduction to the Encyclical Fratelli Tutti, seek to bring to light and make explicit the profound link between the present Social Magisterium and the affirmations of Vatican Council II.

Sometimes this link is not seen at first sight, and I try to explain why. In the history of Latin America, in which I have been immersed, first as a young Jesuit student and then in the exercise of the ministry, we breathe an ecclesial atmosphere that has absorbed enthusiastically and made its own the theological, ecclesial, and spiritual intuitions of the Council and has inculturated and applied them. For us, the younger ones, the Council became the horizon of our belief, of our languages, and of our praxis, that is, it soon became our ecclesial and pastoral ecosystem, but we didn’t have the habit of frequently quoting the Conciliar Decrees or pause in speculative reflections. The Council had simply entered our way of being Christians and of being Church and, in the course of life, my intuitions, perceptions, and spirituality were simply generated by the suggestions of Vatican II’s doctrine. There was not much need to quote the Council’s texts.

Today, several decades having passed and finding ourselves in a profoundly changed world — also ecclesial — it’s probably necessary to make more explicit the key concepts of Vatican Council II, the foundations of its arguments, its theological and pastoral horizon, and the arguments and the method it used.

In the first part of this lovely book, Cardinal Michael and Father Christian help us a lot in this respect. They read and interpret the Social Magisterium that I try to take forward, bringing to light something that is somewhat submerged between the lines, namely, the Council’s teaching as fundamental basis, point of departure, place generator of questions and ideas and which, therefore, orients also the invitation I address to the Church and to the whole world today on fraternity. Because fraternity, which is one of the signs of the times that Vatican II brings to light, is what our world and our Common Home need, in which we are called to live as brothers and sisters.

Moreover, on this horizon, the book that I’m going to present has the advantage of rereading in the present the conciliar intuition of an open Church, in dialogue with the world. Vatican II wished to respond to the questions and challenges of the modern world, with the encouragement of Gaudium et Spes; but today, continuing the path traced by the Conciliar Fathers, we realize that what is necessary is not only a Church in the modern world and in dialogue with it, but above all a Church that is placed at the service of men, looking after Creation and proclaiming and realizing a new universal fraternity, in which human relations are cured of egoism and violence and are founded on mutual love, acceptance and solidarity.

If this is what the history of today asks of us, especially in a society strongly marked by imbalances, wounds, and injustices, we realize that this is also in the spirit of the Council, which invited us to read and listen to the signs that come to us from the history of humanity.

Cardinal Michael’s and Father Christian’s book also has this merit: it offers us a reflection on the methodology used by post-conciliar Theology and by the Social Magisterium itself, namely, a historical-theological-pastoral method, in which history is the place of God’s revelation, Theology develops the guidelines through reflection and pastoral care embodies them in the ecclesial and social praxis.

In this connection, the Holy Father’s Magisterium needs to listen always to history and needs Theology’s contribution.

Finally, I would like to thank Cardinal Czerny also for involving a young theologian, Father Barone, in this work. This union is fruitful: a Cardinal called to the service of the Holy See and to be a pastoral guide, and a fundamental theologian. It’s an example of how study, reflection, and ecclesial experience can be combined, and this also indicates a method to us: an official voice and a young voice, together. This is how we must always walk: the Magisterium, Theology, pastoral practice <and> leadership — always together. Fraternity will be more credible if in the Church we all begin to feel ourselves “brothers” and to live our respective ministries as a service to the Gospel and to the building of the Kingdom of God and the care of the Common Home.

Saint Peter’s, Rome, October 3, 2021, first anniversary of Fratelli Tutti.

Translation by Virginia M. Forrester

Related

Cardinal Parolin at the Novendalia Mass: “Mercy leads us to the heart of faith”

Exaudi Staff

27 April, 2025

8 min

Pope Francis’ Tomb in Santa Maria Maggiore

Exaudi Staff

27 April, 2025

1 min

Mercy and the joy of the Gospel are two key concepts of Pope Francis

Exaudi Staff

26 April, 2025

9 min

Thousands of faithful bid farewell to Pope Francis in St. Peter’s Square

Exaudi Staff

26 April, 2025

2 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)