Pope Sees Auschwitz Survivor Lydia Maksymowicz

One of Dr. Josef Mengele’s Victims

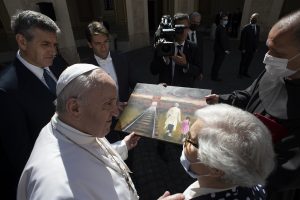

During this morning’s General Audience, Pope Francis had a spontaneous meeting with Lydia Maksymowicz, a Polish woman of Byelorussian origin who survived the Nazi concentration camp in Auschwitz and the experiments of Dr. Josef Mengele, known as “The Angel of Death.”

As “Vatican News” reported today, May 26, 2021, the Holy Father kissed the deportation number to the concentration camp, which Lydia has tattooed on her arm. Then Lydia gave the Pontiff three gifts, as symbols of memory, hope, and prayer, saying: “you have strengthened me and reconciled me with the world.”

Visit to Rome

As “Vatican News” reported, Lydia Maksymowicz, one of Nazism’s last survivors in Europe, now living in Croatia, visited the Italian capital as a guest of “The Living Memory of Castellamonte” in Turin, where she will give her testimony to young people, experience already picked up in the documentary “The Girl Who Couldn’t Hate.”

After her fortuitous meeting with the Holy Father, Lydia Maksymowicz expressed her closeness to him. “After John Paul II, I love Pope Francis. I follow his ceremonies on television, I pray for him every day, I am faithful to him and I profess profound affection for him.” And, she continued, she and the Pontiff “understood one another with the eyes; we didn’t have to say anything, words weren’t necessary.”

Her meeting with the Pope took place on a special day for her — Mother’s Day in Poland. “For me, it’s a special anniversary, because I’ve had two mothers: the one who gave birth to me and whom they stole from me in the concentration camp when I was 3, and the Polish mother who adopted me once we were free and to whom I owe my salvation.”

Presents for the Successor of Peter

At the end of the Audience, the victim of Nazism gave the Bishop of Rome three gifts symbolizing the three pillars that support her life: memory, hope, and prayer. The first is represented by a blue and white fringe scarf with the letter P for Poland, on a red triangular background, which all the Polish prisoners use in commemoration ceremonies.

Hope was represented in a picture painted by her assistant, Renata Rechlik, who portrayed her as a child, holding her mother’s hand, while watching from afar the entrance paths to the Birkenau camp, symbol of the beginning and end for millions of Jews and other prisoners. Finally, prayer: Lydia placed a Rosary in Pope Francis’ hands with an image of Saint John Paul II, blessed by her godson, Father Dariusz. “It’s the one I use every day to pray,” she said.

Hope was represented in a picture painted by her assistant, Renata Rechlik, who portrayed her as a child, holding her mother’s hand, while watching from afar the entrance paths to the Birkenau camp, symbol of the beginning and end for millions of Jews and other prisoners. Finally, prayer: Lydia placed a Rosary in Pope Francis’ hands with an image of Saint John Paul II, blessed by her godson, Father Dariusz. “It’s the one I use every day to pray,” she said.

Lydia’s Story

At 3 Lydia, her mother, and her maternal grandparents were taken from their home and deported, suspected of being collaborators with the partisans. “I was small, very young, but I already had much experience after having lived war scenes in the former Soviet Union. I was prepared for pain, for the evil done by men against other men. However, I did not expect to experience what I lived through in Auschwitz,” she continued.

“I was deported in a train apt only for animals, perhaps not even for that. When the doors opened, I saw terrible sights. My grandparents were separated from us and from the others and then sent to a bunkhouse with a chimney from which smoke with an atrocious odor issued. My mother and I, dirty, hungry, frightened, obeyed the soldiers who shouted incomprehensible words while dogs barked. We didn’t understand anything; we did everything we were told; we were terrified,” she added.

Dr. Mengele’s Victims

Both were identified in the camp as Polish prisoners, with the letter P sowed on their striped uniforms. Her mother was taken to the workers’ bunkhouses. Lydia, instead, was taken to a “house full of children of different ages and nationalities.” It was the bunkhouse where Dr. Josef Mengele worked, one of those responsible for the attempt to exterminate the Jews.

That house was the deposit Mengele used to carry out his experiments with pregnant women, twin babies, and people with malformations. They sent Lydia to him because she was a “pretty and healthy girl.” After 80 years, she doesn’t remember what he did with her small body, but she does remember well “the pain” and his look. “He was an atrocious person, without limits or scruples. Day after day, many persons lost their life by his hands. After the War, books were found with references to tattooed numbers, including mine,” she concluded.

Related

Pope at Gemelli Hospital: Peaceful Night

Exaudi Staff

12 March, 2025

1 min

Pope Francis spent a peaceful night at the Gemelli Polyclinic

Exaudi Staff

11 March, 2025

1 min

Pope Francis shows stable improvement

Exaudi Staff

10 March, 2025

1 min

“The Lord is with us and takes care of us, especially in the place of trial”

Exaudi Staff

09 March, 2025

8 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)