Pope: Be Servant of Life, Not Master

'Rethinking Anthropology – A Necessary Humanism'

We are asked to be “a servant of life and not its master… a builder of the common good with the values of solidarity and compassion.”

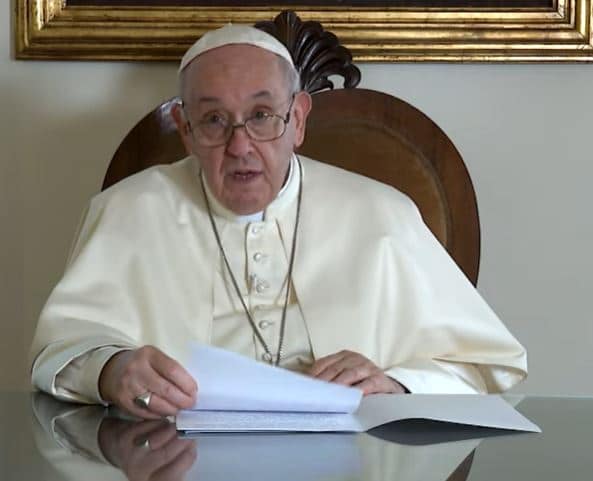

That was the reminder Pope Francis gave today in a video message to the opening session of the plenary assembly of the Pontifical Council for Culture. The theme of the assembly is “Rethinking Anthropology – A Necessary Humanism”; the Pope stressed that the objective is not to fight with humanism but to make it Christian.

“Today, a revolution is underway – yes, a revolution – that is touching the essential nodes of human existence and requires a creative effort of thought and action. Both of them.,” the Pope said. “There is a structural change in the way we understand generation, birth, and death.

“The specificity of the human being in the whole of creation, our uniqueness vis-à-vis other animals, and even our relationship with machines are being questioned. But we cannot always confine ourselves to denial and criticism. Rather, we are asked to rethink our presence in the world in the light of the humanist tradition: as a servant of life and not its master, as a builder of the common good with the values of solidarity and compassion.

“Indeed, at this juncture in history, we need not only new economic programs and new formulas against the virus but above all a new humanistic perspective, based on Biblical Revelation, enriched by the legacy of the classical tradition, as well as by the reflections on the human person present in different cultures.”

Following is the full text of the Holy Father’s video message, provided by the Vatican:

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

I am pleased to address my cordial greetings to you on the occasion of your Plenary Assembly, postponed because of the pandemic and now convoked, albeit in virtual mode. This is also a sign of the times we are living in: in the digital universe, everything becomes incredibly close but without the warmth of presence.

Moreover, the pandemic has challenged many of the certainties our social and economic model is based on, revealing its fragilities: personal relationships, working methods, social life, and even religious practice and participation in the sacraments. Also, and above all, it has forcefully re-proposed the fundamental questions of existence: the question about God and the human person.

This is why I am struck by the theme of your Plenary: Rethinking Anthropology – A Necessary Humanism. Indeed, at this juncture in history, we need not only new economic programs and new formulas against the virus, but above all a new humanistic perspective, based on Biblical Revelation, enriched by the legacy of the classical tradition, as well as by the reflections on the human person present in different cultures.

The term “humanism” reminds me of the memorable speech given by Saint Paul VI at the end of the Second Vatican Council on 7 December 1965. He evoked the secular humanism of the time, which challenged the Christian vision, and said: “The religion of the God who became man has met the religion (for such it is) of man who makes himself God”. Instead of condemning or vilifying this, the Pope resorted to the model of the Good Samaritan that had guided the Council’s thinking, namely an immense sympathy for people and their achievements, joys and hopes, doubts, sadness, and anguish. And so, Paul VI invited the humanity that was closed against transcendence to recognize our new humanism, because – he said – “we too, we more than anyone else, are the cultivators of man”.

Almost sixty years have passed since then. Secular humanism – an expression that also alluded to the totalitarian ideology then prevalent in many regimes – is now a thing of the past. In our era marked by the end of ideologies, it seems to have been forgotten, it seems to have been buried under the weight of the new changes brought about by the digital revolution and the incredible developments in the sciences, which force us to rethink what it is to be human. The question of humanism stems from this question: who is the human person?

At the time of the Council, a secular, immanentist, materialist humanism came face-to-face with a Christian one, open to transcendence. Both, however, could share a common basis, a fundamental convergence on some radical questions related to human nature. This has now disappeared because of the fluidity of the contemporary cultural vision. It is the age of liquidity. However, the conciliar Constitution Gaudium et Spes is still relevant in this respect. It reminds us, in fact, that the Church still has much to give to the world, and it obliges us to acknowledge and evaluate, with confidence and courage, the intellectual, spiritual, and material achievements that have emerged since then in various fields of human knowledge.

Today, a revolution is underway – yes, a revolution – that is touching the essential nodes of human existence and requires a creative effort of thought and action. Both of them. There is a structural change in the way we understand generation, birth, and death. The specificity of the human being in the whole of creation, our uniqueness vis-à-vis other animals, and even our relationship with machines are being questioned. But we cannot always confine ourselves to denial and criticism. Rather, we are asked to rethink our presence in the world in the light of the humanist tradition: as a servant of life and not its master, as a builder of the common good with the values of solidarity and compassion.

This is why you have placed some essential questions at the center of your reflections. Alongside the question on God – which remains fundamental for our very human existence, as Benedict XVI often reminded us – today the question on the human being and the identity of the person is posed in a decisive manner. What does it mean today to be a man or a woman as complementary persons called to relate to one another? What do the words “fatherhood” and “motherhood” mean? And again, what is the specific condition of the human being, which makes us unique and unrepeatable compared to machines and even other animal species? What is our transcendent vocation? Where does our call to build social relationships with others come from?

The Sacred Scripture offers us the essential coordinates to outline an anthropology of the human person in relation to God, in the complexity of the relations between men and women, and in the nexus with the time and the space in which we live. Biblical humanism, in fruitful dialogue with the values of classical Greek and Latin thought, gave rise to a lofty vision of the human person, our origin and ultimate destiny, our way of living on this earth. This fusion of ancient and biblical wisdom remains a fertile paradigm.

However, biblical and classical humanism today must wisely open itself to receive, in a new creative synthesis, the contributions of the contemporary humanistic tradition and that of other cultures. I am thinking, for example, of the holistic vision of Asian cultures, in a search for inner harmony and harmony with creation. Or the solidarity of African cultures, to overcome the excessive individualism typical of Western culture. The anthropology of Latin American peoples is also important, with its lively sense of family and celebration; and also the cultures of indigenous peoples all over the planet. In these different cultures, there are forms of a humanism which, integrated into the European humanism inherited from Greco-Roman civilization and transformed by the Christian vision, is today the best means of addressing the disturbing questions about the future of humanity. Indeed, “when human beings fail to find their true place in this world, they misunderstand themselves and end up acting against themselves” (Laudato Si’, 115).

Dear Members and Consultors, dear participants in the Plenary Assembly of the Pontifical Council for Culture, I confirm my support for you: now more than ever the world needs to rediscover the meaning and value of the human being in relation to the challenges we face. Today we need to repeat those pagan verses: “Sunt lacrimae rerum et mentem mortalia tangent”.

I bless you from my heart, and I ask you to continue to pray for me. Thank you very much!

© Libreria Editrice Vatican

Related

His Hope Does Not Die!

Mario J. Paredes

24 April, 2025

6 min

Francis. The Human and Religious Imprint of a Papacy

Isabel Orellana

24 April, 2025

5 min

A Pope’s Last Journey: Francis’ Body Transferred to St. Peter’s

Exaudi Staff

24 April, 2025

3 min

Cardinal Felipe Arizmendi: With the Risen Christ, There Is Hope

Felipe Arizmendi

24 April, 2025

6 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)