Persistence of brain activity during the dying process

A recent study published in the journal Philosophy, Ethics and Humanities Medicine(1) refers to research carried out on dying patients that has been able to demonstrate how the global cerebral hypoxia that occurs in these patients after the withdrawal of the artificial ventilatory support to which they were subjected notably stimulated, in some of these […]

A recent study published in the journal Philosophy, Ethics and Humanities Medicine(1) refers to research carried out on dying patients that has been able to demonstrate how the global cerebral hypoxia that occurs in these patients after the withdrawal of the artificial ventilatory support to which they were subjected notably stimulated, in some of these patients, the brain activity recorded in the electroencephalogram (gamma activity). As the authors of the research emphasize, this finding suggests that the brain of a patient in the process of dying may still be very active. Likewise, the conclusions of this study point out the need to reevaluate the role of the brain during cardiac arrest.

The aforementioned gamma activity in the electroencephalogram, a pattern of brain waves found in the frequency of around 30 to 100 hertz, is not a manifestation of residual brain activity; In contrast, these gamma waves are high frequency and are commonly associated with higher cognitive processes, such as sensory perception, memory, attention, and information processing. Gamma activity in healthy people is especially noticeable during situations where increased mental activity is required, such as learning, problem-solving, and intense concentration. It has been observed that the synchronization of gamma activity in different brain regions is related to the integration of information and the coordination of cognitive functions.

This, and other similar studies, confirm the erroneous belief that in all patients neuronal activity decreases during the phases close to death. Experimental studies in animals have found that phase coupling between gamma brain waves and alpha and theta brain waves occurs in the first 30 seconds after cardiac arrest and is accompanied by an increase in gamma brain waves. Similar increases in brain wave activity have also been observed during choking and hypercarbia events.

The discovery of these cerebral electrical phenomena forces us to make various considerations of the dying process, among which are:

How should we interpret the fact that brain activity increases during the death process in humans?

How long should one wait to establish the diagnosis of death after cardiac arrest?

Do patients in whom organ donation is performed in asystole present the same cerebral phenomena described in other dying patients?

Is it ethically correct to make the diagnosis of death if brain activity still persists during the period of asystole?

There is a majority of agreement, clinical and legal, that the death of a human being can be established, from an organic point of view, when there is a complete and irreversible cessation of brain functions. The diagnosis of death through verification of the irreversible absence of brain activity (brain death) has been accepted for decades as the death of the person. However, it cannot be forgotten that the lack of cardiac activity is not synonymous with death, since the cessation of heart activity is not necessarily accompanied by the immediate cessation of brain activity. On the other hand, the effectiveness of cardiopulmonary resuscitation performed after cardiac arrest has been demonstrated, which not only can reverse it, but, in a considerable percentage of patients, achieves an ad integrum recovery of brain functions. Although there is multiple experimental and clinical evidence that has shown that cardiac and respiratory arrest, the main mechanisms that trigger death, cause complex time-dependent changes in neuronal activity that sometimes lead to brain death, it is also true that brain damage can be reversed with successful resuscitation.

From all this, it must be inferred that cardiac arrest should only be considered a sign of death when the cessation of cardiac activity is irreversible and is also accompanied by an irreversible cessation of brain activity. Therefore, after cardiac arrest, without intention to resuscitate, once sufficient time has elapsed for circulatory cessation to be accompanied by cessation of brain electrical activity, the diagnosis of death of the person can be established. However, the aforementioned electroencephalographic studies suggest that time must elapse after cardiac arrest to establish the diagnosis of death (sufficient for integrated neuronal activity to cease).

The fact that there are discrepancies between different authors about how much time is necessary, after the cessation of cardiac activity, to establish that the cessation of brain activity is irreversible, may lead us to conclude that the establishment of especially short times, such as that some legal frameworks establish, could lead to the diagnosis of death being established in patients in whom not only brain activity persists, but also a potential total recovery of it.

Evidence of the disagreements in establishing the diagnosis of death after cardiac arrest is the fact that there are significant disagreements in the temporal criteria required for the diagnosis of death in the so-called “donors with a stopped heart”(2). While in some countries, such as Germany, this type of donation is prohibited, in those where it is legislated, the “non-touch time” (time from the complete cessation of cardiac activity until measures can be initiated) typical of organ extraction) shows extreme variations. Thus, in some countries it is considered that only 2 minutes of asystole are needed for the declaration of death, 5 minutes in Spain, 10 minutes in Switzerland, Austria and the Czech Republic, while in Italy the time required is 20 minutes.

Philosophically, death is the irreversible state where the integrative unity of the organism as a whole has been lost; The organism is no longer more than the sum of its parts, and irreversibly cannot resist the disintegration brought about by the forces of entropy. When we talk about death, it is useful to review the models used to explain it: Death is a biological/ontological event that cannot be changed. According to J.L. Bernat, death is the event that separates the process of dying (one is still alive, although death is imminent) from bodily disintegration(3). The same author maintains that death is a univocal state of an organism, and irreversible (“if the event of death were reversible, it would not be death but part of the dying process that was interrupted and reversed”) (4).

It is important to take into consideration the ordinary meaning of the term “irreversible” which is “that cannot be reversed” and “depends on what physically can or cannot be done.” The clear meaning is that “no known intervention could have eliminated it.”

In the case of patients in whom there has been a cessation of cardiac activity, with persistence of brain activity, we can consider that it is a “reversible” situation (“that can be reversed”), and given the possibility of reversibility, it could not be considered this situation as permanent.

The main promoters of non-heart donation have maintained that death is not primarily an ontological or moral issue, but rather “a fundamentally question of medical practice”(2). In addition, they argue that when doctors usually declare death based on cardio circulatory criteria, they declare it based on the cessation of cardiac activity, without waiting times.

These claims are misleading and inaccurate. The death of the person is an ontological concept, with physiological bases and moral extension. On the other hand, it is important to establish whether the patient “is dying” or “is dead.” The process of dying is not synonymous with death. It is, therefore, relevant to establish not only the permanence of the situation, but also its irreversibility, where irreversibility means “that it cannot be reversed” and not “that there is no intention to reverse.”

When a situation is not reversed it is considered “permanent”, but if a condition can never be reversed, it is considered “irreversible”. In other words, irreversibility implies permanence; Permanence does not imply irreversibility.

The consensus on the moral acceptability of non-heart donation supports the weak construct of the equivalence of “irreversibility” and “permanence.”

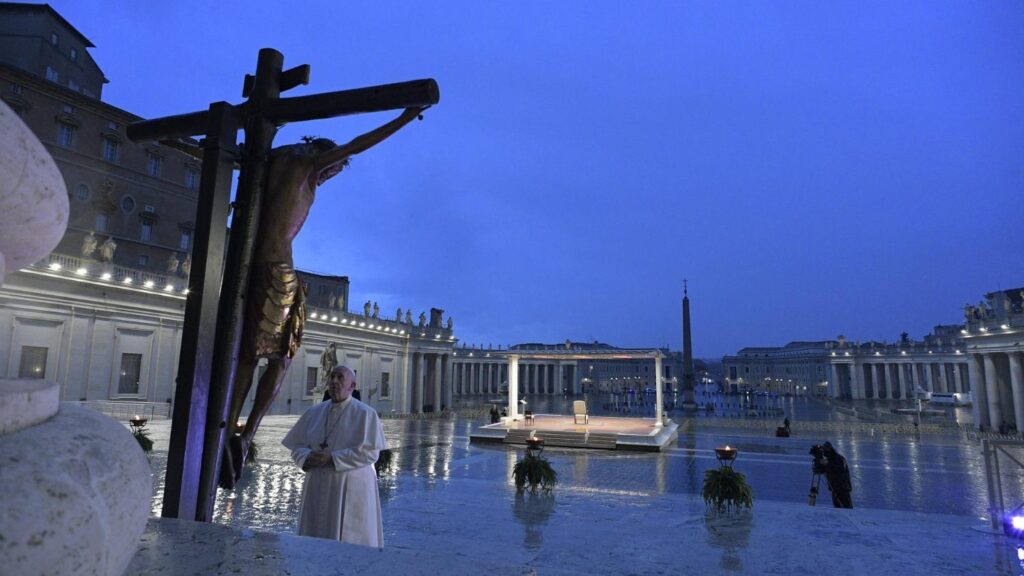

The existence of brain activity during the first phases after cardiac arrest demonstrated in multiple studies, such as the one cited at the beginning of this article, should not only lead to the consideration of the importance of the persistence of person characteristics in human corporeality, and consequently the incompatibility with the diagnosis of death, but also leads to considering this phase of the dying process, a relevant period of life that must be accompanied from a medical and also spiritual point of view.

Jose María Domínguez Roldán – Member of the Bioethics Observatory – Life Sciences Institute – Catholic University of Valencia

- Xu G, Mihaylova T, Li D, Tian F, Farrehi PM, Parent JM, et al. Arises from neurophysiological coupling and connectivity of gamma oscillations in the dying human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023;120(19):e2216268120.

- Joffe AR, Carcillo J, Anton N, deCaen A, Han YY, Bell MJ, et al. Donation after cardiocirculatory death: a call for a moratorium pending full public disclosure and fully informed consent. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2011;6:17.

- Bernat JL. Are organ donors after cardiac death really dead? J Clin Ethics. 2006;17(2):122-32.

- Bernat JL. How the distinction between «irreversible» and «permanent» illuminates circulatory-respiratory death determination. J Med Philos. 2010;35(3):242-55.

Related

His Hope Does Not Die!

Mario J. Paredes

24 April, 2025

6 min

The Religious Writer with a Fighting Heart

Francisco Bobadilla

24 April, 2025

4 min

Francis. The Human and Religious Imprint of a Papacy

Isabel Orellana

24 April, 2025

5 min

Cardinal Felipe Arizmendi: With the Risen Christ, There Is Hope

Felipe Arizmendi

24 April, 2025

6 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)