Love triumphs over death in Leisen, Bergman and Wenders

What many of the great films in the history of cinema show is the victory of love over death

The alliance between philosophy and cinema allows for grateful thought. It pays attention to the whole aspect of gift that exists in our life and expresses it with words. Films reflect life and in that context death is easily presented, not as the last word. On the contrary, many of the great films in the history of cinema show the victory of love over death. In what sense? We believe that the philosopher Gabriel Marcel expressed it in a precise way in one of his plays, Le Mort de demain: “Aimer un être, c´est lui dire: «Toi, tu ne mourras pas.» / “To love someone is to say to them: «You will not die.»”[1]

At this moment, those of us writing from Valencia do so with the extreme experience of a tragedy. The DANA with the subsequent flood, which has claimed more than two hundred and ten lives to date. And we want to follow closely the reflections recently published by Dr. Carola Minguet Civera, Director of Communications at the Catholic University of Valencia, in her column Has the flood revealed anything to us?, when she rightly concludes:

At this moment, those of us writing from Valencia do so with the extreme experience of a tragedy. The DANA with the subsequent flood, which has claimed more than two hundred and ten lives to date. And we want to follow closely the reflections recently published by Dr. Carola Minguet Civera, Director of Communications at the Catholic University of Valencia, in her column Has the flood revealed anything to us?, when she rightly concludes:

«…in the flood a revelation has been given. The Apocalypse of Saint John reveals the Lamb, who is Love. The caritas, the agape, has been revealed in the small things: in the muddy boots; in the walks along the destroyed roads with mops, buckets, jugs of water and food; in every hug and in all the tears shared. Death has spoken tyrannically, with an unbearable roar, but the Valencian people have answered it. The last word is not theirs, although it may seem so in these hours of crying, mourning and desolation. It is Love. And the waters cannot drown it.”[2]

We are capable of looking death in the face and giving it meaning

The image that death can be defeated, as proposed by Dr. Minguet, is not foreign to the cinema screen.

Let us dwell on three examples in which death is represented by a character with whom one can dialogue. In all of them it is an exchange of thoughts and emotions that is fruitful. The cinema records that “from time immemorial all human cultures have been symbolizing Death with a physical aspect, with a real entity” [3]. When death is personified, a fundamental human experience is being captured. We are capable of looking death in the face and giving it meaning. There is something deeply rooted in the human condition that makes it know that the tyrannical appearance of death is not incompatible with us being able to find meaning for it. And in this sense, overcome it. The key is to find a way of living that confronts it: the ability to love and the determination to make it flourish.

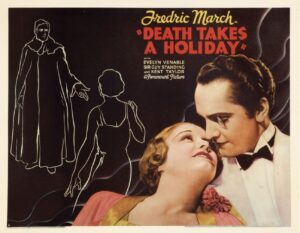

The first of the films we are going to analyze was directed by Mitchell Leisen (1898-1972). It was based on a play by the Italian Alberto Casella (1891-1957), adapted for the Broadway theater by Walter Ferris (1882-1965) with a script by Maxwell Anderson (1888-1959) and Gladys Lehman (1892-1993). In it, Death on Vacation [4], the character who represents it, Prince Sirki (Frederic Marcha), imposes his presence in the mansion of a nobleman, Duke Lambert (Sir Guy Standing), forcing him to welcome him as a guest, but the other guests ignore his true identity and treat him normally. Death has wanted to be incarnated in this way so that he can experience first-hand what human life consists of, why people fear the end of their days, what they spend their time on. He takes a three-day vacation, at the end of which he will return to his usual terrible appearance.

A love is greater than illusion… and stronger than death

To explain human development, an old retired diplomat, Baron Caesarea (Henry Travers), tells him that there are three games that people strive for, “money, love and war.” And he adds that the most decisive is love, of which no one gets tired. Prince Sirki will seek to have this experience, for which he will first flirt with a young American woman, Rhoda (Gail Patrick). She

soon suspects that the person she believes to be an attractive nobleman is simply analyzing the feelings she arouses in him, and leaves him upset (“If I’m not your type, well, I’m not your type!”).

With the second girl, Alda (Katharine Alexander) does not want to make the same mistake. She does not want to be limited to superficial feelings and asks him to give her his soul. To do this, she must know him as he is and still love him. When Sirki reveals himself to her with the face of death, Alda flees in terror.

It is with the third young woman, Grazia (Evelyn Venable), that Sirki truly experiences love, recognizing the communion that has been created between them. Then he feels an enormous paradox: having to abandon the human condition, Death will feel that he is dying because he is going to lose the young woman with whom he has fallen hopelessly in love. His surprise will be enormous when Grazia wants to go with him, because she has not stopped seeing death in him. She has not stopped at his terrible aspect, but has been able to capture all his kindness. Death then says the last lines of the film: “Then there is a love which casts our fear and I Have found it! An loves is greater than illusion… and strong a death.”

Mitchell Leisen tells of a very dear friend of hers who had lost her son in a very extreme situation, which had left her devastated. One day I fired a shot in the air. I took her into the screening room, left her alone, and had her shown Death Takes a Holiday. She came out totally changed. She said, “You have explained death to me, made it beautiful for me. I don’t feel like I used to anymore.” This meant a lot to me and made it worth all the effort if you could touch so many people like that and explain to them something that used to horrify them. As Death itself says, “Why are people afraid of me?”[5]

“Death Takes a Holiday” sends the message that our view of death can change, if our view of life is not governed by superficiality and other distractions, but by love. The love of Leisen’s friend for her son could be added to Gabriel Marcel’s expression: “You will not die.” Some may refuse to see it that way. We are free to act in this way. What is not so clear is why this particular choice of freedom should be obligatory for everyone and dogmatically bury hope.

Ingmar Bergman’s (1918-2007) “The Seventh Seal” very subtly poses what the victory of love over death consists of. Based on a play written by the director himself, it presents the battle between man and death in a very plastic way. The knight Antoninus Block (Max von Sydow) obtains a postponement of his end by means of a game of chess with Death (Beng Ekerot). The latter accepts it because she is very fond of this sport. We can translate it into a strategic logic that seeks to finish off the other by means of checkmate.

The knight Block has been able to set his sights on the only ray of goodness that pierces the blackness of the story

For the times of catastrophe that we are experiencing these days in Valencia, the film “The Seventh Seal” is particularly illuminating. The film depicts a social climate of complete pessimism due to the spread of the Black Death and the sense of failure in the crusade in which the knight has participated. His squire Squire Jöns (Gunnar Björnstrand) reflects the radical skepticism that can be experienced as a result. In any case, he is shown to be healthier than the preaching that terrifies with the divine wrath of the monks or with the condemnation of a young woman (Maud Hansson) accused of having had sexual relations with the devil, who ends up at the stake.

For the times of catastrophe that we are experiencing these days in Valencia, the film “The Seventh Seal” is particularly illuminating. The film depicts a social climate of complete pessimism due to the spread of the Black Death and the sense of failure in the crusade in which the knight has participated. His squire Squire Jöns (Gunnar Björnstrand) reflects the radical skepticism that can be experienced as a result. In any case, he is shown to be healthier than the preaching that terrifies with the divine wrath of the monks or with the condemnation of a young woman (Maud Hansson) accused of having had sexual relations with the devil, who ends up at the stake.

Such a world, between extreme rationalism and religious fanaticism, is a completely hopeless world. But the knight Block has been able to set his sights on the only ray of goodness that pierces the blackness of the story. The comedy actor Jof/Joseph (Nils Poppe) in his innocence and good will to brighten the lives of others – not without some bragging – is capable of having beatific visions. He sees the Virgin Mary teaching the infant Jesus to walk. Although he is considered a dreamer and a fraud, even by his own wife, Mia/Mary (Bibi Andersson), he forms a close-knit and loving family with her and their common son Mikkael (Tommy Karlson), capable of the same joy and hospitality that the knight himself benefits from. Jof hopes to make his son the most wonderful juggler, capable of suspending a ball in the air.

There is a playful kindness in the image of the family

Death had not understood why he wanted to postpone his denouement. But in the last scenes we understand. Thanks to the sinister character being able to fix his attention on the board, the family of actors was able to escape his domination. They did not become part of the dance of death in the last frame. The sunny dawn after the rain was reserved for them. In one

of his Diaries, Bergman confesses:

… The Holiness of the Human Being. Jof and Mia represent something important to me: if one takes away theology, the Holy remains.

There is also a playful kindness in the image of the family. The child will perform the miracle: the juggler’s eighth ball must remain still in the air for a dizzying instant—a microsecond.[6]

He explains further:

As far back as I can remember, I have carried with me a deep, sickly fear of death, a fear that became unbearable during puberty and up to the age of twenty-eight.

The thought that when I died I would disappear, that I would go through the dark portal, that there was something I could not control, or prepare or foresee, was a constant source of horror for me. That I suddenly took the plunge and managed to give Death the form of a white clown, a character who talked, played chess and who, in reality, had no secrets, was the first step in the victorious fight against the fear of death.[7]

It is not far-fetched to think that in the knight Block’s fight against death the victory is for compassion or mercy. The nobleman forgets himself and is able to enjoy the place where the sources of life are found. He defeats death by removing the innocence of Jof and his family from its clutches. The dark character’s absent-mindedness in letting them escape can be thought of as an unconfessed complicity, snatched away by the nobleman.

The kind character of death in Palermo Shooting has precedents in Death on Holiday

In Palermo Shooting by Wim Wenders (b. 1945) we see that in the character of death there is something of the two previous films. It is true that Wenders in the press kit for the Cannes Festival, recognized the influence of Bergman’s work[8], but not so much the Leisen film. However, it is not difficult to recognize that the kind character of death in Palermo Shooting has precedents in Death on Holiday.

The film was written by Wim Wenders himself and focuses on the character of Finn, a hugely successful photographer, played by the singer of the band Die Toten Hosen, Campino (b. 1962, in Düsseldorf, the same city where Wenders was born). It shows his evolution from a frenetic and superficial life to a deeper reunion with himself. This is made possible by two converging factors: the messages that death sends him and the discovery of his first true love in the person of an Italian art restorer, Flavia (Giovanna Mezzogiorno). And by the urban context in which these events take place: the city of Palermo that gives the film its title.

It is here that Frank (Dennis Hopper) shoots some arrows to wake Finn from his reverie. And he introduces himself in this way: “Death… is an arrow from the future that comes straight to you.” The dialogue between Frank and Finn reveals the proper way in which it should be conceived. Enrique Fuster explains:

Death (who wears white, because for Wenders it is light) tells him that it makes no sense for people to thank the doctor for giving birth and, however, not thank death, who does the same thing (giving birth), on the other side of the road (min. 92): death engenders life (Marcel[9], 160, 294, 307). Finn asks her what she can do for him, for death, and she basically tells him: show that you no longer fear me (they hug) and make me known to the world (and asks him to photograph her). When she photographs him, in death, he sees his mother, the same one he carried on his shoulders in a previous scene. And before, at another moment in the conversation, death appeared with Finn’s face; because I am everyone, she tells him.[11]

Death is the exit door, the only one. He who fears life, the real world, he who does not know how to live, fears death

Later, Enrique Fuster specifies:

Death is the exit door, the only one. He who fears life, the real world, he who does not know how to live, fears death. And the fear of life is the fear of death. In the end, death gives him back his camera and asks him to take a photo, and while he poses, a door opens behind death and a beam of white light floods everything, as if to signify that it is, indeed, an exit to Life. [12]

The encounter with death allows Finn to look with new eyes at the woman with whom he is beginning a relationship, next to whom he lies modestly dressed, overcoming for the first time in a long time the sleep problems that plagued him.

In bed, Finn opens his eyes. He says to himself: “for the first time in a long time, now is now.” Flavia also opens her eyes, looks at him and says: “you” (min. 97). She names him by looking at him. The encounter, the relationship, the identity that is established and that makes him feel loved (Marcel [13], 164). If man is a relationship, for there to be an “I,” I need someone to say “you.” And I know myself, I understand myself, I identify myself, only from the other, from the relationship, from (or starting from) the trusting gaze of someone who loves me. [14]

Brief conclusion

Perhaps «Palermo Shooting» is the most explicit in terms of the message we have expressed throughout this contribution: “Death is the exit door, the only one. Those who fear life, the real world, those who do not know how to live, are afraid of death.” With the pain caused by a tragedy such as the one that has struck us in Valencia in recent days, one can be tempted to think that death is the final thing. But it is not so. The lack of indifference that so many deaths produce in us speaks of a logic of compassion that does not resign itself to so much pain and so much heartbreak. And at the same time, it is a recognition that those who have left us so abruptly have somehow mysteriously won our hearts more deeply. That the promise of immortality that love reveals to us is not a dream, but a completely reliable indication.

Perhaps «Palermo Shooting» is the most explicit in terms of the message we have expressed throughout this contribution: “Death is the exit door, the only one. Those who fear life, the real world, those who do not know how to live, are afraid of death.” With the pain caused by a tragedy such as the one that has struck us in Valencia in recent days, one can be tempted to think that death is the final thing. But it is not so. The lack of indifference that so many deaths produce in us speaks of a logic of compassion that does not resign itself to so much pain and so much heartbreak. And at the same time, it is a recognition that those who have left us so abruptly have somehow mysteriously won our hearts more deeply. That the promise of immortality that love reveals to us is not a dream, but a completely reliable indication.

Bioethics, in short, is a scrupulous application of the first principle that constitutes civilization: “thou shalt not kill,” which concentrates all its meaning on the person of the poorest, smallest and most vulnerable whom we can threaten. However, the imperative not to end life does not entail a continuous suspicion of the malignancy of death. On the contrary, the love with which we embrace life is projected like an arrow towards eternity.

The sad paradox is that many of those who profess the anthropology of “here everything ends,” are friends with the culture of death, and make it a good thing when it comes to the life of the unborn, the elderly, the sick, the vulnerable, which they want to end as a sign of progress. Once again, faced with such a contradiction, the best cinema comes to our rescue. It offers us an environment conducive to reflecting on the victory of love over death, which begins with unconditional respect for all human life… which opens minds to the culture of life in the face of the tyranny of death.

José Alfredo Peris-Cancio – Professor and researcher in Philosophy and Cinema – Member of the Bioethics Observatory – Catholic University of Valencia

***

[1] Marcel, G. (1931). Le mort de demain. In G. Marcel, Three Pieces. I regard you neuf. Le mort de demain. La Chapelle Ardente (pp. 105-185). Paris: Librairie Plon, p. 161.

[2] Minguet Civera, Carola, Has the flood revealed something to us?, https://religion.elconfidencialdigital.com/opinion/carola-minguet-civera/nos-ha-revelado-algo-riada/20241105052543050738.html

[3] Díaz Maroto, C. (2011). The death of vacation. Madrid: Notorious Ediciones., p. 8.

[4] We have discussed this film more extensively in Sanmartín Esplugues, J., & Peris-Cancio, J.-A. (2019). Cuadernos de Filosofía y Cine 05. Personalist and community elements in Mitchell Leisen’s filmography from its beginnings to “Midnight” (1939). Valencia: Catholic University of Valencia San Vicente Mártir, pp. 79-90.

[5] Chierichetti, D. (1997). Mitchell Leisen. Hollywood Director. San Sebastián-Madrid: San Sebastián International Film Festival-Filmoteca Española, p. 76.

[6] Bergman, I. (1992). Images. Diaries of a filmmaker. (J. Uriz Torres, & F. J. Uriz, Trads.) Barcelona: Tusquets editores, p. 208.

[7] Ibid., p. 212.

[8] Cfr. https://cinemadedemain.festival-cannes.com/en/f/palermo-shooting/

[9] In Marcel, G. (2022). Homo viator. Prolegomena to a metaphysics of hope. (M. J. De Torres, Trans.) Salamanca: Sígueme.

[11] Fuster Cancio, E. (2024). “The visible and the invisible in Wim Wenders’ «Palermo Shooting»”. VI International Congress of Philosophy and Cinema., Author’s manuscript. p. 5.

[12] Ibid., p. 6

[13] Homo viator, cit.

[14] Fuster Cancio (2024), cit., p. 6

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)