Love in times of trial

She rejoices with him; she suffers with him; she is excited about his projects and shares the daily routine of life with him

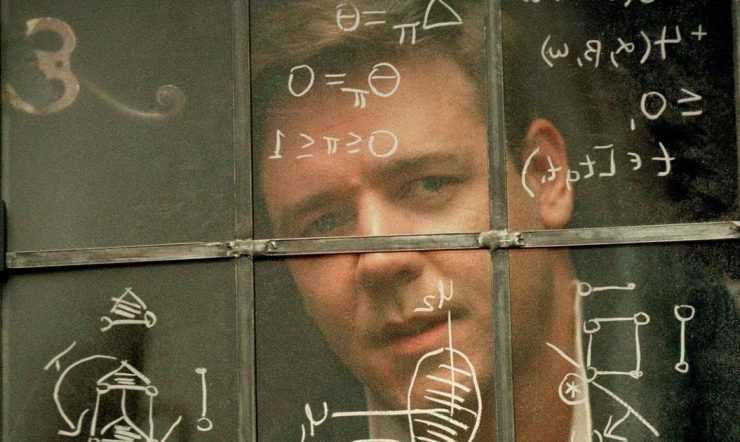

The film “Brilliant Mind”, which won the Academy Award at the time, tells the story of John Nash, a professor at Princeton University who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Economics in 1994. Nash, played by Russell Crowe, despite his eccentric character, his fixation on discovering original ideas and his poor social skills, was highly regarded as a university professor. In 1953, he marries a student, Alice (Jennifer Connelly) who is captivated by his genius and innocence. It is then that the symptoms of a degenerative paranoid schizophrenia become evident, forcing him to be committed to a psychiatric hospital.

The film in question prompts me to reflect on those marital situations in which one of the partners bears the brunt of the relationship. Not only in relation to an illness – such as Nash’s – but to any disability that forces a change in the ordinary dynamics between the spouses. In such circumstances, is it possible for love to flourish and endure? The “healthy” spouse offers, contributes… but does he or she receive? What about the natural and legitimate satisfaction of his or her personal needs linked to his or her status as man or woman?

When a severe decline in some capacity occurs after the spouses have realised their life project together, i.e. in old age, the attention, care, renunciation and dedication is understandable from the perspective of loyalty, shared intimacies and affection nurtured over the years, because, “building the conjugal history does not mean watching together as the years go by, it means giving those years a special communal meaning, because it contains the peculiarities of each and the singularities of the two in the framework of a continuous complementing and becoming one” ([1]) But when the decline in capacities occurs at the dawn or in the spring of marriage, after the initial bewilderment and amazement, acceptance and continuity in cohabitation becomes an uphill struggle.

Ordinarily, love is built thanks to the concurrence of sensitive, physical and intellectual elements; of shared illusions, of joint efforts, of pain, of details and grievances, of gifts and even of discussions… all these elements water it abundantly so that it can germinate and preserve its splendour. Love is exclusive because it captures and is made with the uniqueness and unrepeatability of the loved one. What is proper to the person is his or her intimacy, his or her “I” that distinguishes him or her from others, giving him or her a special and endearing value over others. Love educates that which is permanent, that which transcends, that which is temporary, circumstantial and accidental. That significant “someone”, with a name that evokes their irreducible presence, invites us to walk together, cementing a path paved with the uniqueness of each one. Consequently, if love penetrates and is woven with the substance of the loved one, the accidental does not revoke him or her, nor does it annul his or her selfhood or personhood. Over the diminution of capacities, its reality as a person rises untouched and, for this very reason, it maintains the condition of lover and loved one.

In a notorious diminution of capacities, the expressions that accompany love are affected. It becomes more “dry” and in a certain sense, even “arid”. It is logical that this should be so. While one spouse lavishes care and attention on the other, the other, focused on their pain or incapacity, struggles to find answers that make sense of their new situation. Is a colour film better than a black and white film? The brightness, the luminosity, the colours in a marital relationship do not come from the outside. They come from within and from the human qualities of the spouses, or from one of them when circumstances force it.

Love is a gift. It is given without demanding merit in return. Love is understandable from the logic of gratuitousness. There is no single reason to love, there are many intrinsically intimate and peculiar ones, turned into ineffable arguments whose apogee is expressed in a simple and consistent: because I do, because I want to.

To love is a hymn to human freedom. Welcoming the person – distinguished as the beloved – is such a personally free decision that it is only expressed with a simple ‘porque me da la gana’, a traditional phrase that encapsulates the purest meaning of love. However, this freedom of ‘wanting to want to love’ comes to life and matures hand in hand with responsibility. Love entails obligations, commitments not only with respect to the feeling that binds, but above all with the totality of the person of the beloved. This capacity to respond becomes evident and extremely necessary when one of the spouses is going through a situation that limits his or her actions. In the spousal relationship, then, the time of deeds, of care, of continuous attention and constant concern emerges. This period marked by giving without receiving could give the impression of ‘drying up’ the conjugal relationship. However, this is not the case; reciprocity in giving and receiving is not only established when what is given is returned. Reciprocity exists when the spouse accepts, values and appreciates what is given. This way of communicating makes love grow and become more fruitful, because love grows to the extent that the personal “I” is diminished in order to focus effectively on making the spouse happy.

Finally, Alice, in deciding to focus her life on John, welcomes him not as a nurse welcomes a patient, but as her husband, who among his many characteristics has a special one: illness. This acceptance leads her to update her love to her husband’s reality and circumstances: she rejoices with him; she suffers with him; she is excited by his projects and shares the daily routine of life with him. Alicia’s life has not been a minor one. It has been enriched by John’s presence as a companion, husband and loved one; it has been enlarged because she was loyal and faithful to her freely assumed commitment; and it has been adorned with the wise maturity she values. He discovers, cares for and contemplates the intimate and mysterious reality of human weakness to which he gives himself with solicitous dedication.

[1] Camere, Edistio, The family, an optimistic view, Ed. Mar Adentro, Lima, 2007.

Related

Lent, let us aim for 10

Alfons Gea

13 March, 2025

5 min

Cardinal Arizmendi: The Pope, Successor of Peter

Felipe Arizmendi

12 March, 2025

4 min

Isidro Arenas: The Voice That Overcame Polio and Made Us Dream of Tennessee

Mar Dorrio

12 March, 2025

2 min

Hope

Luis Francisco Eguiguren

10 March, 2025

3 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)