Knight of the tongue, wanderer of the spirit

I met him when, riding on the back of the chivalric novel of Arthurian origin, he was Dean of General Studies at the Universidad Simón Bolívar. Shortly after meeting each other, our conversations were dominated by comments about the shed tears by the gallon in dozens of chivalric adventures. We both taught, with different approaches, general studies on Don Quixote to students of engineering, pure mathematics, biology and computing –we have also been Quixotes in front of the blackboard–, to which he added courses on Mariano Picón Salas and books of chivalry, his two literary passions

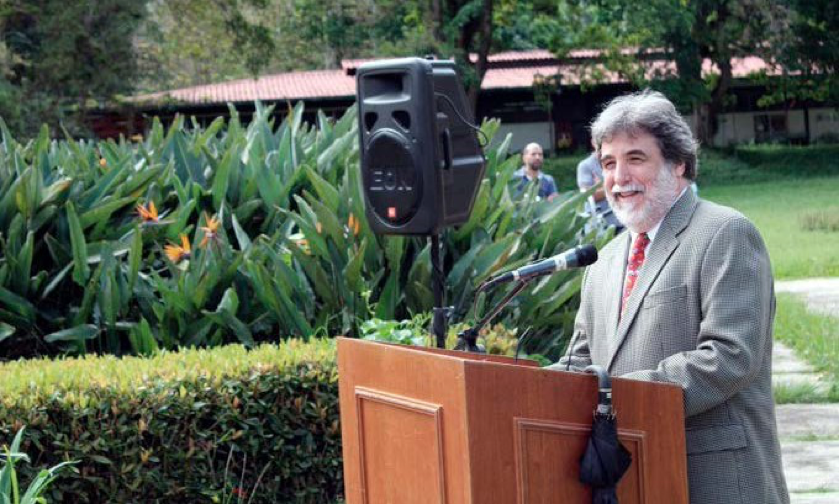

“And climbing high on the great scaffold, when he saw Tirante’s body, his heart wanted to break, and anger forced his spirit to be able to climb onto the bed and with many tears he threw himself on Tirante’s body… Let me kiss him many times for the contentment of my soul! The afflicted lady kissed the cold body with such force that her nose broke, from which a lot of blood came out, her eyes and face were full of it, and all those who saw her cry shed many tears of pain and compassion”1. If it had not been for Cristian Álvarez I would have missed reading that violent, bloody and tearful kiss, perhaps the most passionate of the literature recorded west of the Jerusalem claimed by crusaders and knights. I met him when, on the back of the chivalric novel of Arthurian origin, he held the Deanship of General Studies at the Simón Bolívar University. Shortly after we met, comments about the shed tears by the gallon in dozens of chivalric adventures predominated in our conversations. We both taught, with different approaches, general studies on Don Quixote to students of engineering, pure mathematics, biology and computing –we have also been Quixotes in front of the blackboard–, to which he added courses on Mariano Picón Salas and books of chivalry, his two literary passions. From then on I met a man whose intellectual integrity in the cultivation of the humanities and the exercise of the essay genre were combined with a modesty and a low public profile that stunned us with its silent simplicity, but not unnoticed in his immediate environment. In all fairness, after three long decades dedicated to literary exercise and its corresponding teaching, Cristian Álvarez has risen to the academic roof –Sillón “W” of the Venezuelan Academy of Language–, without seeking applause or fanfare, only that his work passes through the sieve in the eyes of the reader.

Born for the essay

There are curious coincidences in the life and intellectual history of Cristian Álvarez. Roberto Lovera De Sola published El ojo que lee in 1992, where he included the chapter “A propos del ensayo venezolano”2. Cristian does not appear there, even though he would write penetrating studies close to a very personal philology. In a concise examination of the national literary panorama, Lovera De Sola classifies the country’s essay production from 1960 onwards, but Cristian was a newborn in 1959; there was no way to fit him into the meticulous work. Lovera attributes four or five different tendencies to the genre: the aesthetic essay, the essay of ideas, the critical-literary essay, the essay “purely”, the investigative essay, the psychiatric essay dressed up as good literature by professional doctors – “much of what Abel Sánchez Peláez has published are essays in the strict sense of the word” – in short, he makes a detailed record of those who have dared to write without restrictions or fears, bathing their thoughts in freedom. But Cristian Álvarez’s temporary absence from the literary scene would disappear that same year of the American Quincentennial, when he gave a lecture at Connecticut College in the United States entitled Don Quixote as a sign of the History of America, later published by the Universidad Simón Bolívar, a thoughtful and heartfelt interpretation of the “frontier man” tied to the perpetual dispute between being, being and dreaming, that is, the continental essence of the triple-mestized Creole in whom the spiritual plane frames the existential dilemma in permanent conflict, sometimes to the point of misfortune. “This tragedy – Cristian says – the struggle and tension between these two visions will also characterize later events and even our contemporary history.” Two years earlier, Álvarez had given birth to Ramos Sucre y la Edad Media: el caballero, el monje y el trovador4, in whose introduction he declares his own attitude towards the book to be read: “I confess that I am fond of the study of history, but I prefer even more that magical world of legends, that mythical world that reveals that the soul and the desires and obsessions of man are almost the same throughout all times.” At that moment Cristian begins his intellectual and public journey, and connects with the final objective formulated by other intellects of Venezuelan and Latin American thought: to x-ray the spirit, to search for souls, that is, naked and pure humanism with a mystical projection. Beginning with Mariano Picón Salas himself, of his productive efforts, whose complete work he compiles together with Guillermo Sucre, Cristian recognizes the Spanishness of that man from Mérida who was a permanent spokesperson in favor of the verifiable “spiritual unity of the Spanish world”5. As if emulating the bored but dissatisfied Alonso Quijano, the quixotic sign of America inaugurates Cristian Álvarez’s literary and historiographical contribution to the fin-de-siècle culture, hand in hand with those other previous and multiple minds in the humanistic and Venezuelanist feeling. Cristian remained generationally outside the essayistic orbit of the also academic Roberto Lovera De Sola, but now, side by side in the Academy, perhaps they will try exchanges and writings of quixotic dreams in that genre called essay that the neo-academic fertilizes and cultivates by spreading a metaphysical salt in his writings.

The rest of the work: a mystical humanism

In the midst of the electoral turn of the anxious and historically neglected Venezuela, Cristian Álvarez published in 1999 Going out to reality: a quixotic legacy6. The first part, aptly titled “The Inheritance,” includes the already mentioned quixotic sign in the history of America, adding comments on Ramos Sucre and Picón Salas. Cristian makes a final gloss on the latter to crown the subchapter “Writing in the Land of Grace,” where the love for the beauty of art and nature counteracts “the unbridled history of the 20th century.” Jorge Guillén, Jorge Luis Borges, and Guillermo Sucre also sparkle in the volume, but it is the epigraph “Books on Childhood” about “a plenitude that was had” that most captivates the eyes of the viewer. The reader is grateful for the opportunity to return to reading childhood, where the only things lacking in plenitude were short stature and short pants. On the other hand, dealing with the transcendent human totality, in Mariano Picón Salas’s “Various Lessons”: Consciousness as the First Freedom, published shortly after in Mexico7, there is a suggested meeting of intellectuals summoned by Cristian around a gigantic table, not necessarily round like that of King Arthur and his heroic knights, but polyhedral and vibrant, adapted to a diversity of pulses around secular culture and the plow of the spirit with its constituent elements. More than 130 authors cited or paraphrased from the Marianist humanistic breakdown demand consecutive readings, not for an impenetrable conceptual density, but for the reader’s enjoyment of one who dares to taste the dish of the essay without aesthetic limits. Pages proliferate, four-fifths of which correspond to footnotes, a kind of second parallel volume in case some reader’s dissatisfaction demands more main course to consume. In the larger interpretive tone of the essay on Picón Salas, the exploration of a spirituality historically led by some saints, among many other pure beings, is hindered by demoniacs –Robespierres, Lenins, Mussolinis, Hitlers or Stalins– determined to impose immobile ideologies turned into exclusive genocidal doctrines, advocated by an unburied gallery of demons at the beginning of the third millennium. Faced with the totalitarian threat, Don Mariano proposes “that the even-tempered sense of an exercising conscience points toward the necessary translation of the values of justice and equity into reality, but, yes, without this being able to undermine one iota the responsible freedom of man.” It is the ideological basis on which the path to the spiritual goal opens, a constant in the texts of Álvarez and his favorite authors.

Four essays make up the volume Dialogue and Understanding: Texts for the University8, published in the midst of the political tensions of the century that had just opened to the nation and to the Simón Bolívar University, while Cristian continues to carry his quixotic lances in the turbulent Venezuelan reality. Before assuming the direction of the university publishing house Equinoccio, he put all his effort into creating the Liberal Arts and Studies program at La Simón, just when Hugh Thomas, the famous British Hispanist and member of the House of Lords, says in a presentation on chivalric letters: “I myself have spent a large part of my life pretending to be a Spanish knight.” Cristian does not need to proclaim it publicly: knight-errantry is his intellectual fervor, while he fights for twenty long years against the resistance of the authorities to raise the humanistic program, a symptom of a country in visible institutional dissolution. It aims at the desired but uncertain reconciliation, at the interrupted but free dialogue –Mariano Picón Salas and Josef Pieper present once again–, the respect for dissent, the recognition of the other wherever and however he or she may be, the sticky stain of resentment, the strident stench of populism that destroys coexistence, ethical discussion and the conceit of “I’s”. The same Sartenejas from Barutense receives from Cristian her ¿Repensar (en) la Universidad Simón Bolívar?10, where he summarizes, right from the beginning, the core humanism, because “it is essential for the persistence of the institution and its fundamental objective, as well as for the nation it serves”. That institutional persistence, so solid for decades in Sartenejas that during the 60s it dismantled a bullring to develop a 90-hectare university campus, sounds like a dead letter to us when once a year we go to declare our faith in life to air our bloodless retirement, finding the devastation caused by official abandonment instead of the gardens and facilities once so admired. Despite the abandonment spread throughout the campus, the Uesebista spirit continues to hover over tiled roofs, flying over unburied trees that refuse to give up their green souls.

Revelation and coincidence

On this occasion I failed to fulfill my purpose of not speaking, while writing, to the author under my review, but I apologize because friendship proposes inevitable complicities. Convinced of the mystical character of his humanism, I asked Cristian if he knew of anyone who had previously used such a concept. In a few seconds, she sent me “The Mystical Humanism of María Zambrano,” by Bartolomé Lara Fernández. 11 An unexpected epiphany hit me in the face with an immaterial punch, full of luminous depths. Lara Fernández breaks down such humanism in Zambrano, her permanent touch of the unfathomable nearby, the idea known to history as spirit, so despised by materialism. I, without knowing of previous uses and without telling her, had saddled Cristian Álvarez with a category very much suited to his work, his intellectual life, his university work and his Christian practice. María Zambrano –Cervantes Prize winner 1988, a woman filled with existential baroque–, wounded by the civil war and expelled from her Spanish land, built a philosophical and poetic work where multicoloured souls insist on expressing their perpetuity in the face of men’s disbeliefs. I did not need any further convincing. Thus mystical humanism burst in to apply itself to academic Christianity. I remembered the outburst in Cervantes’ exemplary novel The Force of Blood, where Rodolfo, upon pressing his mouth to the lips of the fainting Leocadia, “was as if waiting for her soul to come out so that he could welcome it into his own.”12 It is the soul that Christian points his finger at to give his opinion on an intellectual expert in analyzing national spirits, Mariano Picón Salas, who is determined to “seek the paths of consciousness.” Thanks to Christian, I was spared the temptation to apply a cheesy note to those episodes where pastoral cries imitate overflowing fountains.

In the chivalric novel, the medieval dream, recast as a Renaissance desire, eludes reason, since it still awaits experimental flirtations to establish itself as an advanced thought. Famines, plagues, and wars persuade the peasant, the villain, fixedsomething, the nobel, and the king to seek the marvelous, restoration from the calamities spread everywhere in fiefs and lordships. A supreme fiction is erected on paper and follows the steps of arms in the Spain reconquered by the knight, an actor who aspires to the sublime. It embodies the irruption of the compensatory dream that, in the words of Viña Liste, exhorts the dreamer to be another being, to seek a higher and grander otherness in an endless wandering, an enterprise only possible among souls looking upwards. He personifies, in my opinion, the mystical humanism where Cristian Álvarez plays the main vihuela, as a knight-errant who, in addition to snatching golden helmets, sings the ballad Suelen las fuerzas de amor / sacar de quicio a las almas…, like Quixote happy to show the other side of breathing to the dukes, duennas, maidens and malicious felines that scratch his face, but do not hurt his soul while he dreams (II, 46). Perhaps it is not then a forced coincidence that when Cristian was born in 1959, Bobby Darin’s song Dream Lover had sold millions of copies throughout the world, as if announcing the universality of the man riding on his spiritual ideal brimming with hunches and daydreams. They often call him Quixote, although his adventures remain diluted.

- Spanish books of chivalry: El Caballero Cifar, Amadís de Gaula, Tirante el Blanco, preliminary study, selection and notes by FelicidadBuendía, Aguilar Editions, Madrid, 1954, 1712-1713.

- Roberto Lovera De Sola, The Eye that Reads, National Academy of History, Caracas, 1992, 265-280.

- Cristian Álvarez, “Don Quixote as a Sign of the History of America”, Studies: Journal of Literary Research, year 3, No. 6, Simon Bolivar University, Caracas, 1995, 117-137.

- Cristian Álvarez, Ramos Sucre and the Middle Ages: the knight, the monk and the troubadour, Monte Ávila Editores, Caracas, 1st edition 1990, 2nd edition

- Mariano Picón Salas, From the Conquest to Independence and other studies, MonteÁvila Editores, Caracas, 1990, introduction by Guillermo Sucre, notes and variants by Cristian Álvarez, 90 and 95-96.

- Coming out into reality: a quixotic legacy, Monte Ávila Editores Latinoamericana – Equinoccio, Caracas,

- The “variational election” of Mariano Picón Salas, UCAB Editions, Caracas, 2021, 1st edition, Autonomous University of Mexico,

- Dialogue and understanding: texts for the university, Equinoccio Publishing House, Simón Bolívar University, Sartenejas,

- Hugh Thomas, “The House of Trade: chivalric novels-chivalric actions”, Antonio Acosta Rodríguez, Adolfo González Rodríguez and Enriqueta Vila Vilar (coords.), The House of Trade and navigation between Spain and the Indies, University of Seville-C.S.I.C.-School of Hispanic-American Studies, Seville, 2003, p. 603.

- Rethinking (in) the Simon Bolivar University?, Editorial Equinoccio, Simon Bolivar University, Sartenejas,

- Bartolome Lara Fernandez, “The Mystical Humanism of Maria Zambrano”, Projection LXIX, (2022), 247-264.

- Miguel de Cervantes, “The Force of Blood”, Complete Works, Editorial Castalia, edited by Florencio Sevilla Arroyo, Madrid, 1999, p.

- Jose Maria Viña Liste (ed.), Medieval Texts of Chivalry, Cátedra Editions, Madrid, 1993, 17 and 51-52.

Related

Reflection by Bishop Enrique Díaz: The Lord’s mercy is eternal. Alleluia

Enrique Díaz

27 April, 2025

5 min

After Eight Days Jesus Arrived: Commentary by Fr. Jorge Miró

Jorge Miró

26 April, 2025

3 min

The Perspectivas del Trabajo Foundation is founded with the aim of promoting virtues for professional development

Exaudi Staff

25 April, 2025

2 min

Reflection by Bishop Enrique Díaz: Alleluia, alleluia

Enrique Díaz

20 April, 2025

5 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)