Kierkegaard and His Mysteries

Existential Dilemmas and Paradox in Kierkegaard's Thought Through His Life and Work

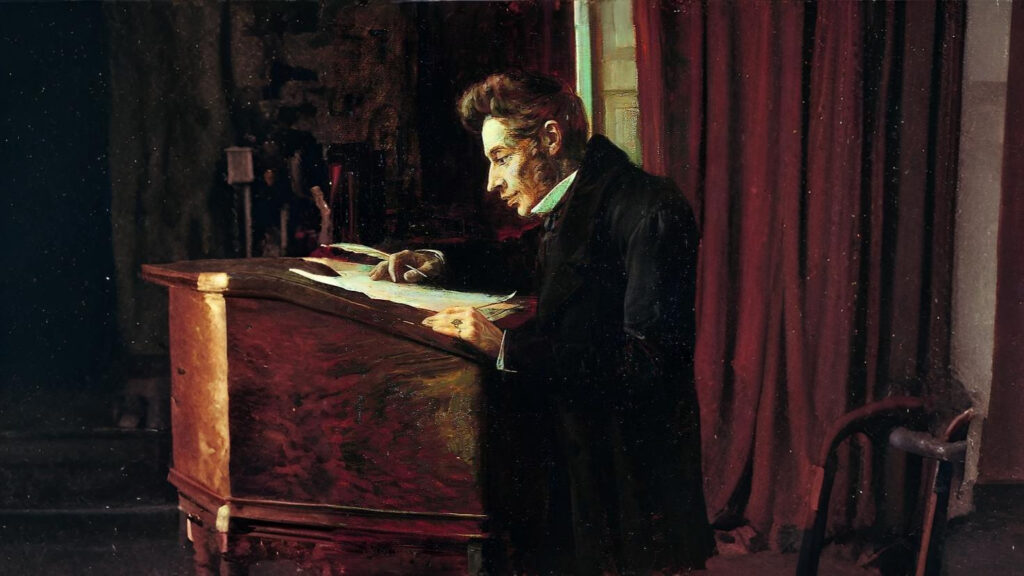

Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855) is a philosopher I read frequently: by or about him. Not everything is easy for me to understand. I am drawn to his defense of the concrete individual over abstract humanity. His critique of Hegel’s rationalist idealism is well-known. A solitary figure, almost a sad figure, he, spear in hand, sets out to lance abstract Christianity in search of the concrete Christian. He sees too much comfort and satisfaction in the culture of his time. He wants to be the gadfly who, by stinging, draws his fellow citizens from their comfort zones. In this Socratic struggle, he is clear: where the destiny of humankind is at stake is in religion.

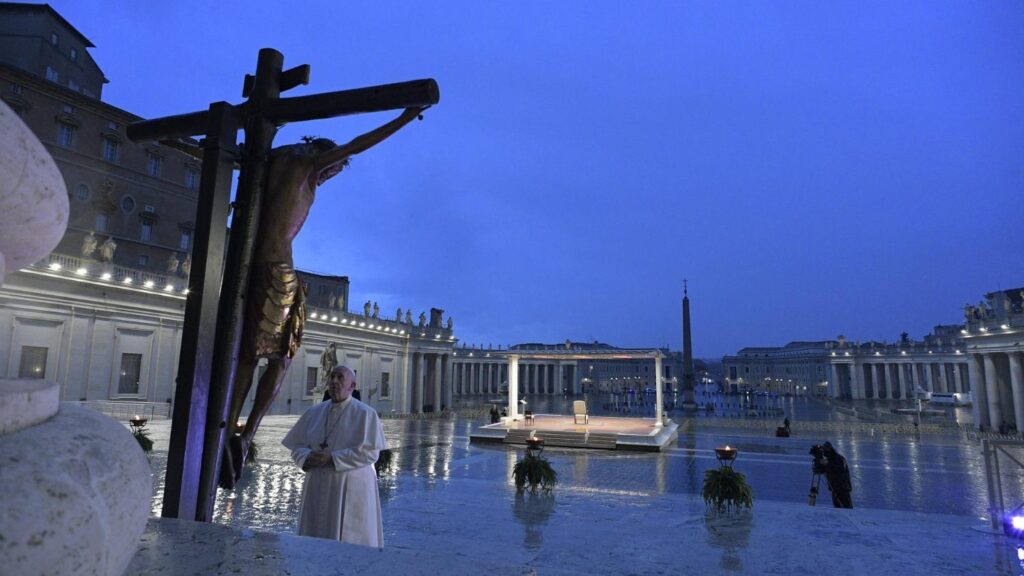

In parallel, I discovered Theodor Haecker (1879-1945), a German philosopher who converted from Protestantism to Catholicism and a great connoisseur of the Danish philosopher, to whom he dedicated two books. The second of these was published posthumously in 1946 and was titled Kierkegaard’s Hump (Rialp, 1956). This emphasis, in contrast to other books that had been published at the time, highlighted Kierkegaard’s weak and somewhat deformed constitution. This somatic condition of our author helped Haecker reflect on the corporeal dimension of the human being and its influence on a person’s character and thought. Starting from the distinction between body, psyche, and spirit, Haecker believes that the spirit elevates the human being above his corporeal dimension. Recently, an example of this assertion is the figure of Saint John Paul II in his last years of pontificate. His body was very deteriorated, his spirit had declined; However, his spirit kept him going until the end of his days.

Haecker’s book addresses several of the themes inherent to Kierkegaard’s existential and intellectual journey. One that continues to haunt scholars of the Danish philosopher is why he broke off his engagement to his girlfriend, Regina Olsen. Kierkegaard’s financial situation was comfortable. Was he in love with Regina? Yes. Was Regina in love with Soren? Yes. So why did he break off the engagement? It seems that Kierkegaard sees the great mission he must fulfill in his life. His goal is to say yes to this, an extraordinary thing that is asked of him, just as God asked Abraham to sacrifice his son Isaac. Believable? Yes, but still a very difficult decision. Only God knows.

Kierkegaard uses irony in his writings. Lucid in his proposals, and also hurtful when he polemicizes with thinkers or theologians. This is the case of Bishop Mynster, of whom Kierkegaard said that “he had corrupted an entire generation and had been nothing less than a poisonous plant” (p. 215). He openly expressed his thoughts and was a champion of sincerity, willing to tilt at any windmills that were put before him. A sincerity, says Haecker, that was never brutal, since he knew how to moderate and limit it, for the sake of piety and love (cf. 216). This sincerity, a hallmark of our philosopher’s character, although so valuable in the affairs of this world, is insufficient in matters pertaining to God and faith. “In relation to God and to the Christian life,” Haecker argues, “the man who, alone and as an individual, constitutes himself as a judge—as Kierkegaard did in the last years of his life—that man, whoever he may be and even if he is endowed with the most perfect human sincerity, stands on an inconsistent basis” (p. 208).

Kierkegaard is a master of paradox, though without Chesterton’s grace and good humor. Haecker celebrates this device and affirms that rationalism dislikes the paradoxical or the language of the paradoxical, and therefore easily becomes boring. To avoid the paradoxical, it excludes from creation not only the irrational, but also the suprarational of the divine; it lacks a sense of mystery (p. 119). Therefore, paradox, in its proper measure, “is a kind of acquiescence of human understanding in the face of the majesty of divine mystery and in the face of the ever-new reality that His ways are not ours” (p. 122). Gabriel Marcel returned to this openness to reality and expansion of rationality decades later in his famous distinction between problem and mystery.

Kierkegaard, a philosopher of luminous reflections on the human condition, an exceptional spirit, lived his life dramatically and conceived it in that same tension. Demand and authenticity were abundant; a sense of humor was scarce, very scarce.

Related

His Hope Does Not Die!

Mario J. Paredes

24 April, 2025

6 min

The Religious Writer with a Fighting Heart

Francisco Bobadilla

24 April, 2025

4 min

Francis. The Human and Religious Imprint of a Papacy

Isabel Orellana

24 April, 2025

5 min

Cardinal Felipe Arizmendi: With the Risen Christ, There Is Hope

Felipe Arizmendi

24 April, 2025

6 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)