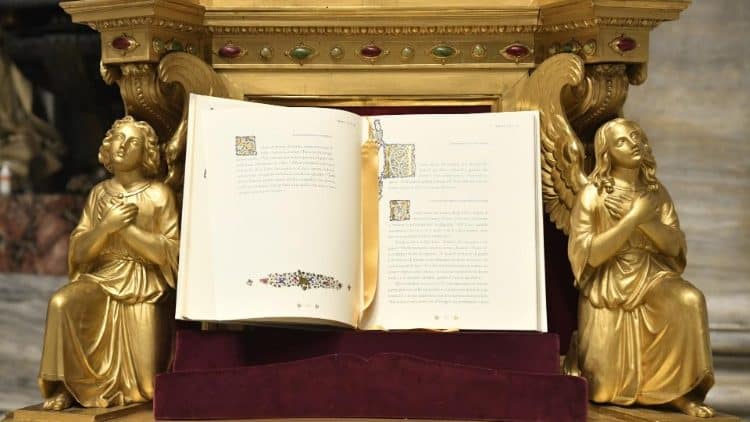

Jubilee, history and roots in Sacred Scripture

In L'Osservatore Romano, the cardinal and biblical scholar traces the origins of the Holy Year, from the Old Testament to the Gospels

It is customary to trace the germinal reality of the “jubilee” to the sound of a ram’s horn: the echo came from Jerusalem, crossed the air, and jumped from town to town. Now, in the Hebrew text of the entire Old Testament, the term jobel appears twenty-seven times: six times there is no doubt that it means a ram’s horn, while the other twenty-one times it refers to the jubilee year. The fundamental page of reference is chapter 25 of the book of Leviticus. It is a complex text, included in the book of the sons of Levi and, therefore, of the priests, a ceremonial book of minute and meticulous regulations relating to the rituality of the temple of Jerusalem.

A philological premise

The term jobel resonates primarily in that text but is also found in chapter 27. The ancient Greek version of the Bible, traditionally known as the Septuagint, confronting this word – jobel – instead of translating it with the recursive “jubilee”, jubilee year, he translated it according to an interpretive canon: áphesis, which in Greek means “remission,” “deliverance,” or even “forgiveness.” This word will be very important for Jesus because – as we will see – he does not speak of jubilee, but rather uses precisely the term aphesis in Luke’s Greek. The word “jubilee” never appears in the New Testament. The Seventy, these ancient translators of the Bible, have, therefore, passed on from an exquisitely sacred cultic fact (the celebration of the jubilee year that begins with the blowing of the ram’s horn on a very specific date, in relation to the solemnity of Kippur, that is, of the Atonement for Israel’s sin) to an ethical, moral, existential concept: the remission of debts, the liberation of slaves (which was the content of the jubilee). The theme of the jubilee moved, therefore, from language and the liturgical act to language and the ethical-social experience. This element is also relevant today to not reduce the Christian jubilee to just a basilar celebration or ritual, but to transform it into a paradigm of Christian life. Some scholars have thought that the term jobel should not be related to the sound of the ram’s horn, but to the Hebrew root jabal, which also means “to send back, restore, dismiss.” The interpretation seems a bit forced, however, because this “dismissal” does not necessarily indicate liberation, it does not have the breath of the aforementioned Greek term aphesis, taken up with special emphasis by Jesus himself. Other philological attempts have offered various explanations, but it must be recognized that the starting element is a ritual data. It represents the sound of the ram’s horn that marked the beginning of a specific year, the tenth day of the autumn month of Tishri, corresponding approximately to our September-October, the month in which Kippur also fell. It is interesting to note that in the Phoenician language, in some ways the elder sister of Hebrew, the same root, that is, the three consonants underlying the word jobel, that is, jbl, denotes the “goat”, a significant component of the Kippur himself. There is no doubt, then, that the sound of the horn, its marking of a sacred time, is at the basis of the term “jubilee”, but we must not forget the tension that leads to the other pole, that of the Greek translation: no It is just a ritual, it is an element that must deeply affect the existence of a people. After this introduction, let us try to collect and illustrate some fundamental jubilee themes that appear somewhat intertwined.

The rest of the earth

According to the biblical text, the first quite original theme is the “rest” of the earth. According to the sabbatical scheme, by which time was measured within the biblical tradition, the earth had to rest every seven years. According to Leviticus 25, the land was also to rest in the jubilee year, which followed seven weeks of years, that is, in the fiftieth. The company seems impractical and difficult to carry out. It is possible to rest the earth for a year, especially in a civilization like that of the ancient Near East, where needs were much smaller than ours and life much more frugal. But letting the land rest for two consecutive years (the forty-ninth sabbatical and the fiftieth jubilee), in an essentially agricultural economy, would have endangered the very survival of the land. Therefore, either the jubilee year was made to coincide with the seventh year of the seventh week, or the jubilee, more than a concrete application, was above all a wish, a utopian sign, a look beyond the usual way of life. . Letting the earth rest is not sowing it and not reaping its fruits. This choice, on the one hand, makes us discover that the land is a gift, because, although in smaller quantities, it still manages to produce something. Its fruits will be scarcer, but they will not be lacking. It is thus remembered that the cycles of nature depend not only on the work of man, but also on the Creator. It is a reminder of another primacy, the transcendent one. On the other hand, in this period there was an attempt to overcome private and tribal property, since each person could take from the land what it offered, without respecting the limits and fences of the cadastre. In practice, it is about the recognition of the universal destination of goods by which everything is available to everyone. This topic can also take on great meaning in today’s society. In it, humanity can be represented by a table set in which there are a few, on the one hand, who have an exaggerated accumulation of goods, and the rest of the people, on the other, a multitude that remains on the sidelines and can only Enjoy leftovers and crumbs. The idea of the universal availability of goods, the antecedent of all private property, no longer exists. In this sense, it is suggestive to refer to the reflections proposed in this regard by the encyclical Laudato si’ of Pope Francis.

The forgiveness of debts and the restitution of lands

The second issue, equally original, is the remission of debts and the restitution in pristinum (to the original owner) of the lands alienated and sold. From the biblical point of view, the land was not a possession of the individual, but of tribes and family clans, each of which had its particular territory. It had been granted during the famous division of the land after the conquest of Canaan, as we read in the book of Joshua (cc. 13-21). Every time, for various reasons, the clan lost its land, it was, in a sense, failing in the division intended by God. With the jubilee, that is, every half century, the map of the promised land was rebuilt, just as God had intended, through the divine gift of dividing the land among the tribes of Israel. Each then received his portion, except the tribe of Levi, who lived off the contributions made by the other tribes for their service in the temple. As for debts, essentially the same thing happened. At the beginning of the jubilee period, everyone was equal, with the same few possessions. Later, however, some had lost their possessions through misfortune, others through laziness or inability. After fifty years, it was decided to return to the starting point, finding everyone at a level of communion of goods that was absolute, ideal, utopian, in equality. Everything remained common and was distributed according to the different tribes. Each family thus recovered their property, their land and all their children. In a call from the book of Deuteronomy, this social renewal is continually proposed to the Jew so that he considers it as the social model that he must live by, although knowing that it is an ideal project that can never be fully realized. In fact, in the book of Deuteronomy we read: “Let there be no needy among you […] and if there is a needy brother among you, do not harden your heart or close your hand” (15:4, 7). An option that is not only ideal adherence to fraternity and solidarity, but also implies the realization of the “hand”, that is, action, concrete social commitment. Let us remember the profile of the Christian community of Jerusalem in which – as Luke reiterates several times in the Acts of the Apostles – “no one called what belonged to him his own, but everything was common to them” (4:32).

The liberation of the slaves

The third structural theme of the biblical jubilee is equally incisive and challenging. The jubilee was the year of the forgiveness not only of debts, but also of the liberation of slaves. The book of Ezekiel (46:17) speaks of the jubilee as the year of liberation, of redemption, the year in which those who had gone to serve to survive misery returned to their homes, with their debts forgiven and their lands forgiven. and freedom recovered. They were once again the people of the exodus, the people free from the layer of lead, from slavery and discrimination. Once again, it was an ideal proposal, intended to create a community that no longer had within it ties of prevarication with one another, that no longer had shackles on its feet and that could walk together towards a goal. It is evident how its relevance also applies to our history in which there is an exterminated number of forms of slavery: drug addiction, trafficking in prostitutes, child exploitation for labor or sexual purposes and child pornography, and so many other ferocious forms of submission. You can also think of all those peoples who are practically slaves to the superpowers because with their debts they are absolutely incapable of being arbiters of their own destiny; the activities of certain multinationals are often a true form of economic tyranny that oppresses certain nations and societies. Therefore, the resonance of the jubilee word of freedom has great meaning even in our time, as does the call to inner liberation. Indeed, one can be externally free but internally enslaved by certain invisible chains, such as social conditioning, mass communication, superficiality, vulgarity and addictions to the infosphere. In a passage from the book of Jeremiah (34:14-17), the prophet forcefully explains the collapse and enslavement of Jerusalem and Judea by the Babylonians in 586 BC. precisely as a judgment from God for the fact that the Jews had not freed the slaves at the Jubilee. Selfishness had caused the great norm of freedom not to be practiced and, as a consequence, there had been a kind of reciprocal punishment on the part of God who had enslaved Israel.

The Jubilee of Jesus

At the beginning of his public preaching, according to the Gospel of Luke, Christ had entered the modest synagogue of his town, Nazareth. That Saturday, he had read an Isaian text (c. 61) and it was his responsibility to proclaim and comment on it. With those words, he had presented himself as sent by the Father to inaugurate a perfect jubilee that would extend throughout the following centuries and that Christians should celebrate in spirit and truth: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me and has sent me to preach good news to the poor, to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to set at liberty those who are oppressed, and to proclaim the year of favor of the Lord” (Luke 4:18-19 ). This is the other root – in addition to the Old Testament – of the Christian jubilee. In the words of Jesus, the horizon of the holy year becomes the paradigm of the Christian’s life, which broadens and encompasses all those sufferings that are the program of the mission of Christ and the Church. The “year of the Lord’s favor”, that is, of his salvation, includes four fundamental gestures. The first is “evangelize the poor”: the Greek verb is precisely at the base of the word gospel, the “good news”, the “good news” of the Kingdom of God. The recipients are the “poor”, that is, the last of the earth, those who do not have the strength of political and economic power, but whose hearts are open to adhering to the faith. The jubilee aims to once again place at the center of the Church the humble, the poor, the miserable, those who externally and internally depend on the hands of God and his brothers. Freedom is the second jubilee act, an act that – as we have seen – was already in Israel’s jubilee. However, Jesus also refers to the prisoners in a strict and metaphorical sense, and here the words that he will repeat in the trial scene at the end of the story are anticipated: “I was a prisoner and you came to see me” (Mt 25:36). . The third commitment is to restore “sight to the blind”, a gesture that Jesus often performed during his earthly existence: let us just think of the famous episode of the man born blind (John, 9).

This was, according to the Old Testament and Jewish tradition, the sign of the arrival of the Messiah. In fact, in the darkness in which the blind man is enveloped, there is not only the expression of great suffering, but also a symbol. There is, in effect, an inner blindness that does not coincide with the physical and is the inability to see in depth, with the eyes of the heart and soul. A blindness that is difficult to eradicate, perhaps more so than physical blindness, which grips so many people into whose souls a ray of light must be injected. Finally, as the fourth and final commitment, liberation from oppression is proposed, which is not only the slavery mentioned above in connection with the Jewish jubilee, but includes all the suffering and evil that oppress the body and spirit. It is what the entire public ministry of Christ will attest. The ideal goal of the authentic Christian jubilee is, therefore, this spiritual, moral and existential tetralogy.

Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi – Cardinal presbyter pro ac vice of Saint George in Velabr

Related

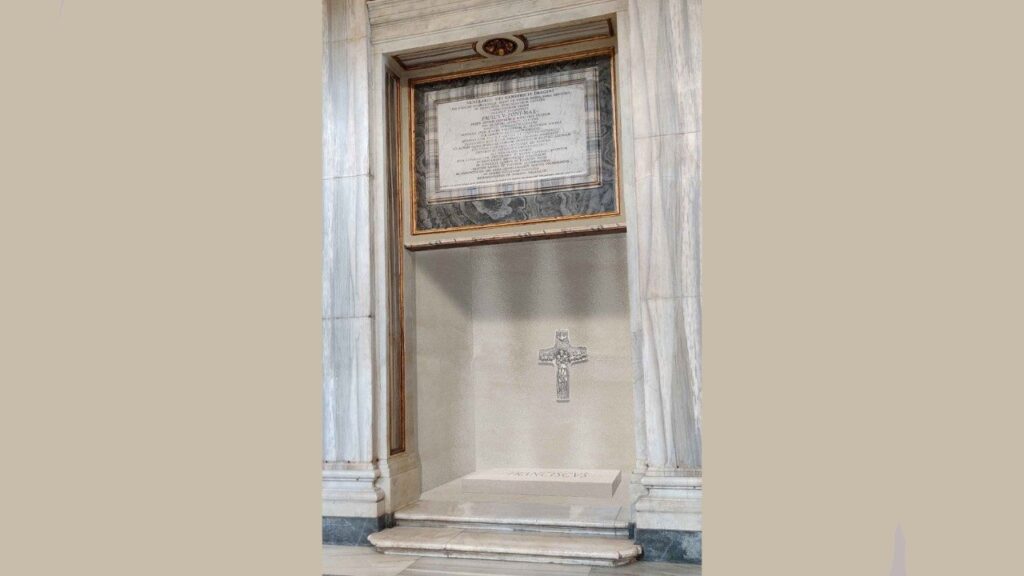

Francis’s Tomb: A Legacy of Humility and Closeness

Exaudi Staff

25 April, 2025

4 min

Cardinals Intensify Their Spiritual and Pastoral Preparation at the Third General Congregation

Exaudi Staff

24 April, 2025

1 min

Rome unites in prayer: the world bids farewell to Pope Francis with love and gratitude

Exaudi Staff

24 April, 2025

2 min

The first General Congregation of Cardinals was held in the Vatican

Exaudi Staff

23 April, 2025

2 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)