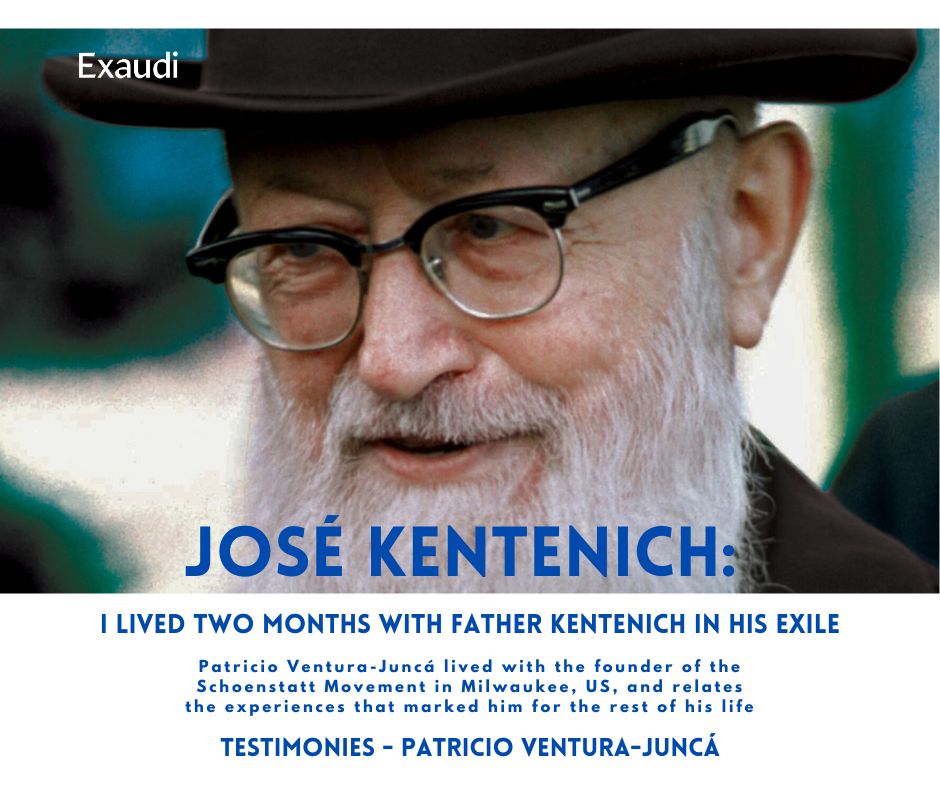

Joseph Kentenich II: I lived two months with Father Kentenich in his exile

Patricio Ventura-Juncá lived with the founder of the Schoenstatt Movement in Milwaukee, US, and relates the experiences that marked him for the rest of his life

In 1949, Fr. Kentenich wrote a letter to the bishop of Trier that would reach the German Episcopate in which he expressed his charism, and offered it to Mary in the Schoenstatt Shrine in Bellavista, Chile, and which would cause an unusual commotion. Within the framework of the celebrations for the 75th jubilee of this act, we present a series of articles related to the subject.

The first article summarizes the facts related to Joseph Kentenich’s exile, his mission for the Church, and the state of his cause for canonization.

***

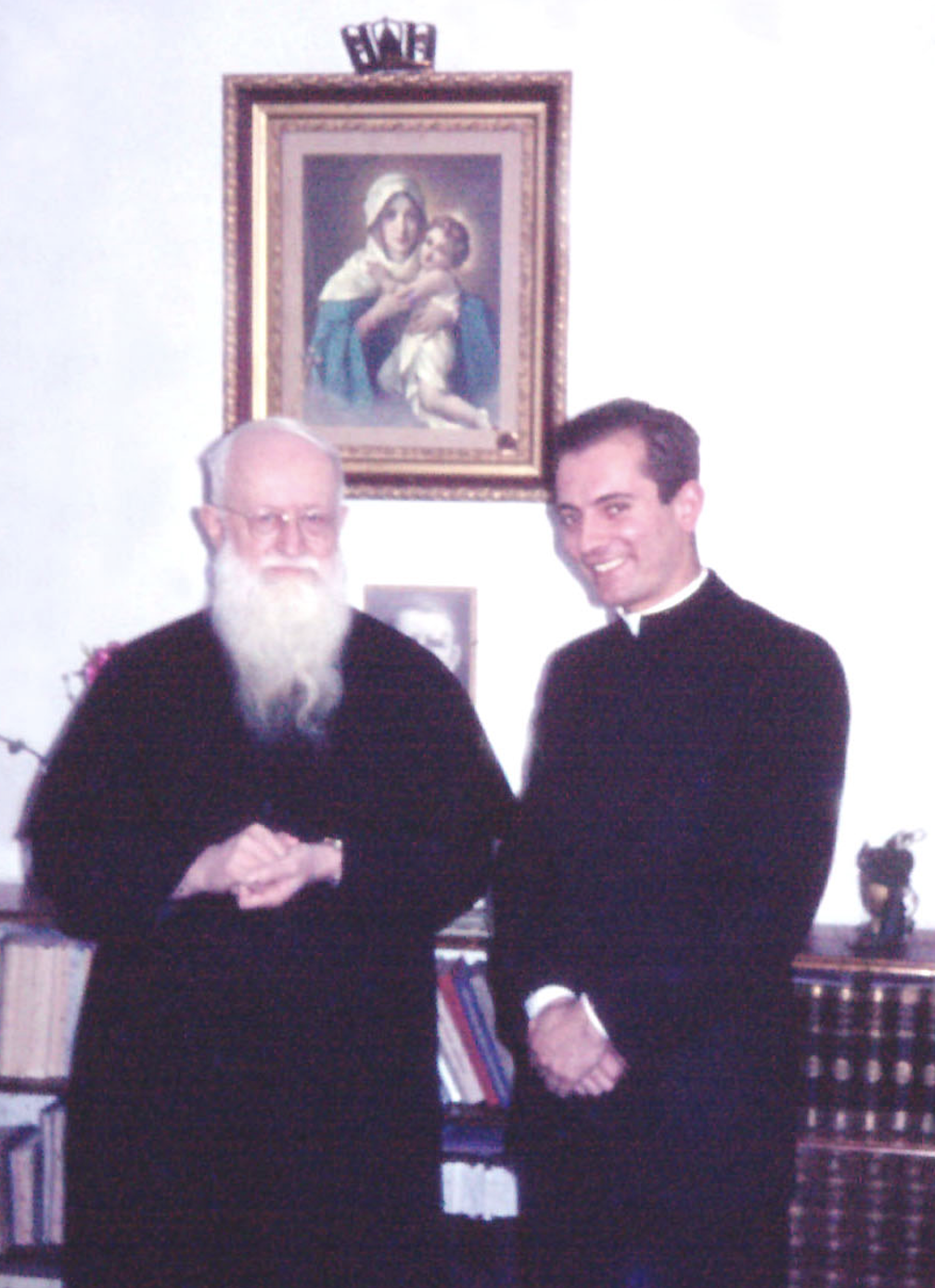

I was 26 years old when in December 1963 I left Rio de Janeiro in a military plane bound for Milwaukee, USA, to visit Father Joseph Kentenich, founder of the Schoenstatt Movement, to which I had belonged since I was 17 years old. The priest was exiled by the Church and I was representing a group of seminarians studying in Santa Maria, Brazil. We wanted to get answers directly from him to some questions about the letter he had written to the Bishop of Trier, and through him, to the German Episcopate, which had triggered his exile.

I had studied medicine for four years, I had a degree in biological sciences and I had had research experience in basic sciences, in neuroscience. Then I entered the seminary of the Pallottine Fathers, the community to which Father Kentenich belonged, which at that time was where we Schoenstatt seminarians studied. I graduated in philosophy, a discipline that captivated me, and I investigated its epistemological relationship with the experimental sciences.

Kennedy answers me personally

It was the Cold War. President John F. Kennedy had just been assassinated in the United States. Months before, we had written to him asking for help to go to the United States because of the importance it had for our formation, but the main intention was to go to see Father Kentenich. In a personal letter, Kennedy wrote back offering us scholarships. That letter would be the key to obtaining the visa for the trip that Father Aquiles Rubin and I would undertake in December 1963.

Pre-conciliar culture calls us to the vision of a renewed Church

In the Church, we lived the pre-conciliar culture, which had little attraction for us. Masses in Latin, homilies far from life, distrust and often rejection of all that was natural. The “no” predominated, with a very vertical juridical structure in which the laity did not have much place.

In Schoenstatt, I had discovered a community ardently committed to change this environment, which we called walking towards the “Church of the new shores.” We lived in a community of young university students on fire for this mission. The Christian West was in decline. Our founder was inviting us to something that was like a great crusade to renew the bonds between the natural and the supernatural, driven by what he called the “fundamental law of love.” It was urgent to renew the Church. Mary, our Mother, always close to Christ, had a central place in this mission to recover the world of personal attachments that captured the whole person in order to meet with the living and personal Jesus Christ. There was a whole world that we probably did not yet grasp in all its depth. We had a very youthful faith and feeling with optimism and hope that had to be tested.

Fr. Kentenich exiled in Milwaukee

The issue was that our founder had been drastically separated from Schoenstatt by the Holy Office, and was exiled to Milwaukee, USA. The Diocese of Trier, where the town of Schoenstatt is located, had sent a visitation to Schoenstatt, and the visitator’s report spoke of a correct orthodoxy of the Movement, but noted that Fr. Kentenich’s pedagogy was not correct. Instead of letting the observations pass and making some changes, the founder responded with a very long letter, presenting the first part on May 31, 1949, at the altar of the Schoenstatt Shrine in Bellavista, Chile. He founded his pedagogy on it, expressing the importance of organic thinking, loving and living, which values natural bonds as a means to deepen the supernatural ones, and thus find the inner harmony that God wants to give us.

Organic vs. mechanistic thinking

For many centuries, human nature was despised as an impediment to reaching God. Fr. Kentenich emphasizes the Thomistic principle, which expresses that grace does not destroy but presupposes, heals, elevates and perfects nature. In this organic thinking, which is opposed to mechanistic thinking, which separates what God conceives as united, Fr. Kentenich sees the core of his mission for the Church. He is aware that the essence of the Christian does not consist in complying with laws and precepts and repeating them, but in having a childlike relationship with God, who is father, who blesses human nature, elevates it through grace and moves us to fill all people with the life of God.

The Letter of the 31st of May and Schoenstatt’s mission

As I said before, I went to Milwaukee with the intention of knowing in detail the mission described in that document, with the purpose of transmitting it to my brothers in Santa Maria. In the first article of this series, the processes related to this letter and Father Kentenich’s exile and liberation are summarized.

The Letter of May 31st symbolizes the so-called “mission of 31st of May.” This refers to Father Kentenich’s vision of the renewal of the Church with organic thinking, loving and living from an integrating theology, philosophy, psychology and pedagogy, and is symbolized in Father Kentenich’s interior act of giving this charism to the Church, and placing the mission, with the risks involved in sending this letter. He does it in the confidence in the Covenant of Love with the Blessed Mother and that God wants it, placing it on the altar in her shrine in Chile.

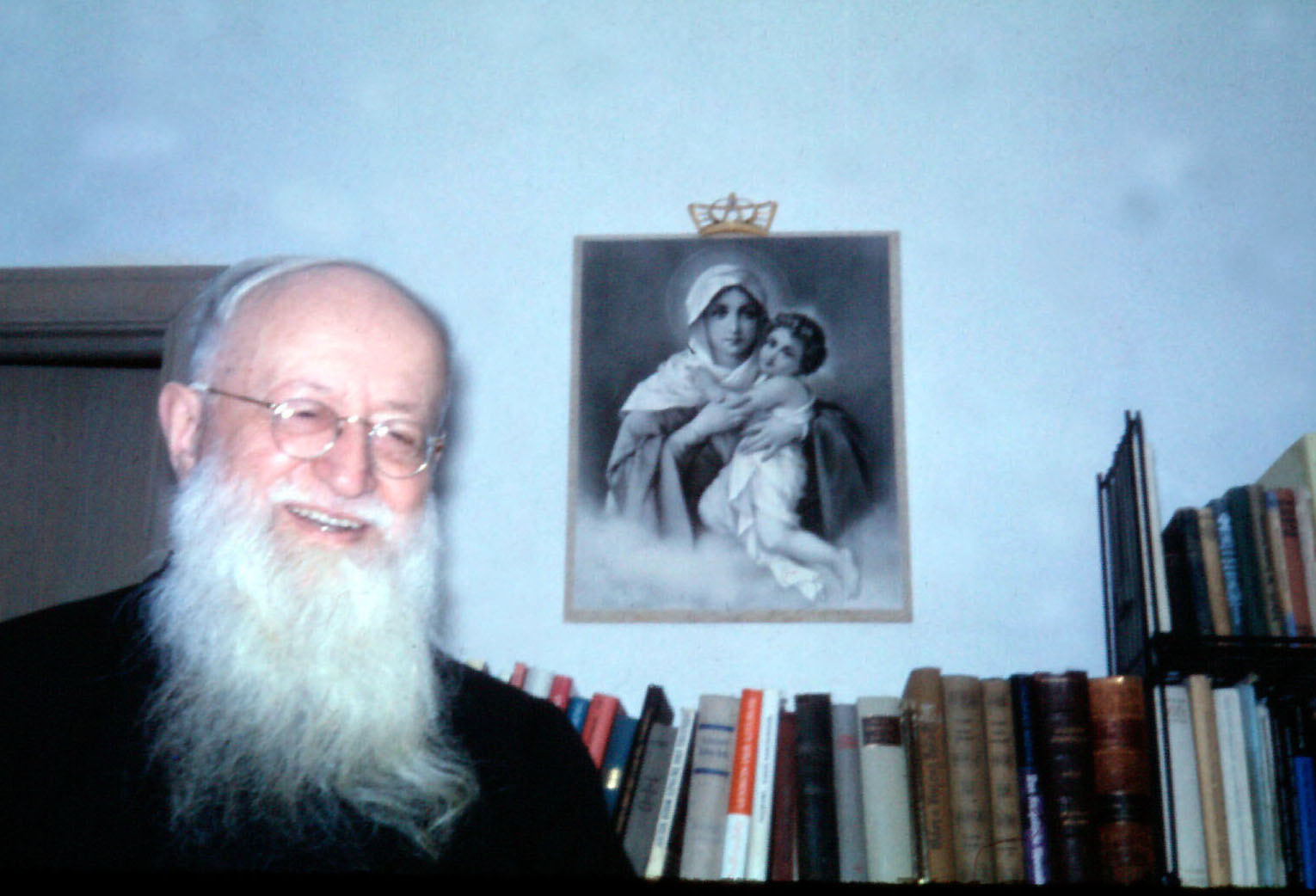

My first encounters with Father Kentenich

We arrived with Father Aquiles in the morning at Holy Cross parish on December 22. We were shown to our rooms where we left our things and settled in. Then came lunch. Before lunch that day there was a short prayer in the house chapel and then we went in procession to the dining room. The superior of the house went first, and the second was Father Kentenich. I was the last one. Everything was new to me. It was the first time I saw Father. He was walking calmly and with dignity. Surprisingly, I saw him leave the line and go to where I was. He looks at me and shakes my hand; he holds it for a moment and says: “Chile”. “Yes,” I reply. A first sign for me. He broke the line to go to greet me, to the mouse, to the last in line. That’s how our relationship began.

The origin of everything is the Covenant of Love with Mary

In the afternoon, Father visited Father Aquiles and me and gave us a basket of fruit. Later on, I had my first meeting with him in a reception room. There I told him why I was coming, I told him of my interest in talking to him about my vocation and the need in our community of Santa Maria to clarify the true meaning of the mission of 31st of May. He listened to me very attentively. I thought and felt that everything I was telling him, even though it was only a brief introduction, was very important and I was hoping perhaps that he would begin with a response. Father looked at me and said something that more or less went like this: “Keep in mind that the origin of all of Schoenstatt is in the Covenant of Love with Mary, from there everything is born.” He touched the table and added: “The Covenant of Love is as real as this table.” These simple words spoken by someone else would not have meant much new to me. But this was very different. I was in front of someone who had lived through it, who had been in the concentration camp and was now in exile, who radiated a lot of life and joy. This had a great impact on me. These simple words of this encounter were the background of my entire stay.

Living together and getting to know each other

The next two encounters were first at the after-dinner meal in the dining room when we were alone talking. There he said to me something like “I will first talk to Fr. Aquiles, who will soon return to Santa Maria. We will have more time, first to live together and get to know each other.”

This phrase has been very important to me: “Living together and getting to know each other.” It was not just about him getting to know me, it was a mutual knowledge, a sharing of life. I kept thinking, maybe I didn’t expect something so simple and with so much depth. This has helped me in many aspects of family issues and pedagogy with communities that we have accompanied with Marita, my wife, in their formation. I have realized that there is a whole world in that phrase. Relationships arise in the best way by getting to know each other, our desires, our life history. Today I speak about a pedagogy of movement, as opposed to rigid molds. Starting from the reality of life and not from pre-made outlines.

I have seen the image of God the Father in a man

I must say that what marked me most in my encounter with Father is the experience of being with a saint. I have repeated this many times, making an analogy with what someone who met the Curé of Ars said: “I have seen God in a man.” More precisely, I would say “I have seen the image of God the Father in a man.” This was very strong for me, because of my history and experiences with my family and Schoenstatt. I found the image of God the Father in a man. I came to try to better understand the mission of the 31st of May and I found the mission incarnated in a person, in his gestures, words, in his being so human and close.

I have never felt so much the closeness of God in a person as in this man. I have never known, I believe, a saint. A saint is someone who fills you with light and brings you closer to God, centrally closer to God who is father. That impact lasted throughout my stay in Milwaukee. It was interesting. I said, “I am next to a person who is a saint, and what an impact a saint can have on one’s life! Many of the things in which I was entangled, complicated, with doubts… are untangled. This contact with him, in that perspective, untangled me, and made me feel free.”

A father that generated freedom, autonomy, independence from him

This feeling of freedom was also something very special. I don’t know if I could fully convey it. I had had contact with other people, who had been in some way spiritual companions: Father Ernesto Durán, Father Benito Schneider… but this sensation of having a person whom I felt so close to, who was so wise, affectionate, welcoming, and at the same time with whom I felt so free… This was not only an intellectual sensation of freedom; it was a psychological-affective sensation of freedom. How could one have a person with his paternity, who is a father, so close, and who made you feel so autonomous, so independent from him. That was something very strong for me from the beginning, very strong!

What interested him most was me

What interested Fr. Kentenich most was my person. There are innumerable gestures, phrases, images and conversations that touched me profoundly. I will try to share some of them.

Vocation to the priesthood and a secret solidarity

About my vocation, he wanted to listen, first to listen without asking too many questions. It was a long story that he heard in a few moments with his eyes closed… Then I thought, a priest of his age, maybe he was tired and fell asleep. Suddenly I was silent, and he realized what I was thinking and told me: “Father is listening.”

Then I thought: it will be enough for this holy man, so full of the Holy Spirit, to tell me if my path was in the priesthood or in marriage. After a few moments of silence, he said something difficult to forget: “Let’s meditate and pray and then we will talk again.” It was perhaps not what I expected, but it was a great learning moment in a nutshell, especially because he said “let’s pray” and not “I’ll pray and I’ll answer you.”

Okay, I said to myself, I’ll do that. A few weeks passed and we talked again. Again, I was expecting a clear direction to decide the way forward, but it was not the case. After some brief considerations he said to me: “I think we can try one more year.” Again “we can try,” not “you can try.” We already had a secret solidarity, a union that gave me a lot of peace and joy. I had to decide, but I was not alone. It was an apprenticeship of practical faith in Divine Providence and in what we call “interwovenness of fate.” Father Kentenich, the Founder, with this young man, without any degrees, with weaknesses, who had gone to visit him, who already felt like a child and who spontaneously asked him everything that came into his head.

The year of discernment was very good, but my doubts about my vocation were accentuated. I wrote to Fr. Kentenich. He knew about my evolution, and through a Chilean priest who visited him, he wrote to me that he recommended that I follow the path of marriage, but that the decision was mine and that whatever it was, I would always count on him. So I made my decision with great freedom, and I never doubted it. In a few weeks I was studying medicine again, and three years later I married Marita.

He never spoke to me about spiritual childlikeness

He listened to everything and answered with great simplicity. He never spoke to me about spiritual childlikeness, so central to our spirituality, but I experienced it with him. Nor did he speak to me about the importance of second causes, how we come to God through people, but I experienced it with him.

His humility: spiritual childlikeness lived

A fundamental trait of Father was his humility. I think this had a lot to do with simplicity and spiritual childlikeness. In some way he had those simple marks, without any fuss, that delicate, direct and authentic spontaneity that one sees in children. It is difficult to transmit these experiences. I see it today in my grandchildren. I saw humility as inseparable from his intimacy with Mary. I saw this from the first day when he spoke to me about the Covenant of Love with Mary. He trusted the Blessed Mother completely, he radiated a tremendous gratitude towards her, which undoubtedly arose since his mother consecrated him to her. She had saved and rescued him since he was a child, she was with him in Dachau and now in exile. To have him there, smiling, loving life, trusting and hopeful with all people, was for me a living miracle of the reality of God’s love and action.

Fr. Kentenich’s fatherhood in confession

I experienced this especially in confession. It was a very profound and simple experience to go to confession with a man of God, with a man who brings you so close to God, to the fatherhood of God. And there is something that I describe as I felt it. Father was so welcoming, so respectful, so simple, and whenever he heard my confession, he always said: “And that’s all?” And I thought: “I believe that if I had a tremendous sin, if I had done a terrible thing, I have the feeling that Fr. Kentenich would receive me as the Prodigal Son.” I even thought of a silly thing… “What a pity not to have a greater sin to be able to feel the mercy of God the Father.” That is the feeling I had with him, something very deep. It is difficult to transmit.

An exile without bitterness, with joy

I would like to share other traits of Fr. Kentenich that I observed in his gestures and actions. He transmitted joy, joy of life, contagious, with a jovial attitude, with something of a child. And I repeated to myself that this is neither obvious nor natural, and even less so in a person who suffered three terrible years in a concentration camp, who is segregated from his family by the authorities of the Church itself, without the possibility of defending himself as he requested, even without being clearly informed of the reasons for keeping him away. This contrast was very impressive for me, this experience that increased as the weeks went by. There was no hint of bitterness or rancorous comment, being aware that the Visitor of the Holy Office had committed a tremendous injustice in the 14 years of exile.

A profound phrase that sprang from the depths of his heart

On one occasion I felt that he opened his heart to me deeply and revealed to me a very intimate moment. It was at a breakfast, and he simply said to me:

“There are moments when one is alone with God – alone with God!”

His face was serious. I didn’t ask and didn’t comment. I had never seen him sad or worried, for he was always radiating joy and peace, but I felt that at that moment he revealed to me an existential loneliness that overwhelmed him. He received very harsh decrees from the Holy Office as a consequence of his answers, which were respectful, but clear and firm. No one dared to confront the Holy Office, but Fr. Kentenich did not measure the consequences when he felt that God was asking him to make such and such a decision. And so he paid the price for the audacity of being authentic.

I was a young man, and I felt his simplicity as he spontaneously shared that experience with me. Father Kentenich was listening, openness, and vital service to others. He was not in the habit of talking about himself. That is why I remembered these words, which came from the depths of his heart.

Now I think that that young man who came from a distant country to see him, to know in depth and in detail his charism and to take the news to the south, was, without knowing it, a close companion, a small source of joy and consolation in the midst of pain. I did not think about it at the time, but a friend made me see it. I, Patricio, without any merit on my part, was important for Father Kentenich at a moment in his life. An unforgettable experience that never ceases to move me.

An encounter that has had an impact on my life in all areas

An encounter that has had an impact on my life in all areas

I end with two words to describe how much the encounter with Fr. Kentenich impacted and still impacts my whole life in my spirituality, in my family, in my apostolate, in my service to Schoenstatt and to the Church. Inspired by the mission of the organic world and to shape Christian values in the world, I dedicated myself for many years primarily to the projection of our charism in the culture through the university, education and science. Later God opened doors for me to dedicate myself also to the interior of the Schoenstatt Movement and the Church.

As a couple, we worked with Marita together in the movement, as educators of various communities of couples. There we were able to experience the pedagogical style that I learned from the Founder. In my work, I always had the goal of projecting our charism as lay people in the temporal sphere. I had the mission of the organic world at the heart of my decisions and those we made with Marita.

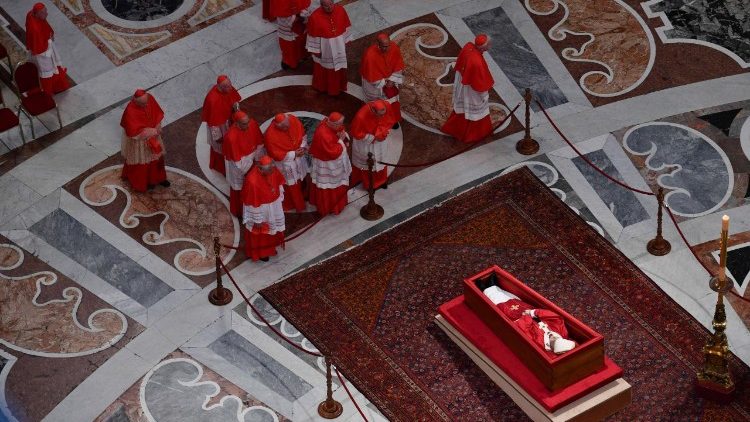

If there is something central that this meeting left me, it was the experience and the importance of paternity at all levels, in God, in the family, in the culture and society. Father Kentenich foresaw how profound the impact of its absence and sometimes even its rejection would be on the new generations. Benedict XVI expresses it in brief words:

“Perhaps modern man does not perceive the beauty, the greatness and the deep consolation contained in the word “father” with which we can address God in prayer, because the father figure is often not sufficiently present today, and often not sufficiently positive in daily life. The absence of the father, the problem of a father not being present in the life of the child is a big problem of our time, so it becomes difficult to understand in depth what it means that God is father for us.” (May 23, 2012)

In a time of serious crisis, a lived response

At a time when the Church is shaken by the ravages of time and especially by her own children, Fr. Kentenich shows us that the answer does not come from foreign ideologies or the rigidity of doctrines and forms, but from an interior life in deep relationship with a God who is father, with Mary, who is mother, and a radical commitment to the destinies of the world, and that this relationship develops in depth when there are human bonds with a father.

At a time when leaders of resistance to the Pope and his magisterium are emerging, Fr. Kentenich shows us a proven fidelity to the Lord, to the Church, to the Pope, in situations of the hardest crosses.

I hope that this simple testimony will help some to get closer to Fr. Joseph Kentenich, to his life witness, to the charism for which he gave himself to the Church of the new times. “He loved the Church” is the epitaph he wanted inscribed on his tomb.

Patricio Ventura-Juncá

As a physician he worked at the university developing clinical and scientific aspects in pediatrics and early life issues. Due to his philosophical formation he became the Director of the Bioethics Center of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. Pope John Paul II appointed him member of the Board of Directors of the Pontifical Academy for Life, where he remained until his 80th birthday. He participates until today in the Academic Committee of the International Academy of Catholic Leaders. With his wife, Marita, he accompanied the formation courses for couples of the Schoenstatt Family Federation.

Related

“We have experienced a brilliant pontificate that has touched the hearts of believers and non-believers alike”

Exaudi Staff

23 April, 2025

6 min

Reflection by Bishop Enrique Díaz: Alleluia, alleluia

Enrique Díaz

20 April, 2025

5 min

Christ is Risen! Alleluia! Commentary by Fr. Jorge Miró

Jorge Miró

20 April, 2025

3 min

Easter: Mystery of Freedom

Carlos J. Gallardo

20 April, 2025

5 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)