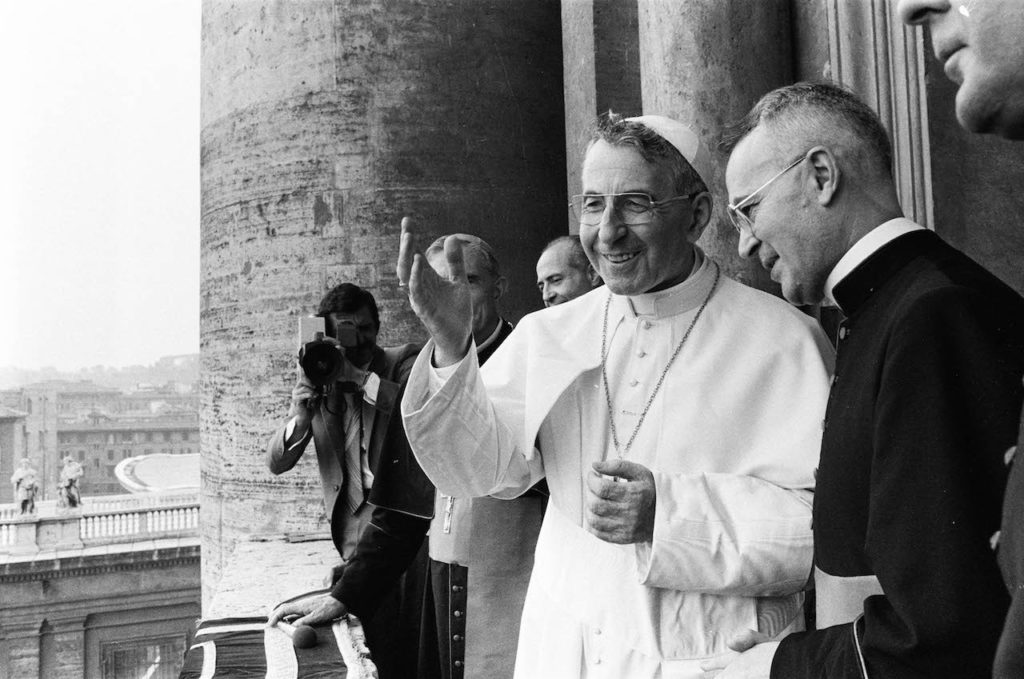

John Paul I Foundation & Private Archive of ‘the Smiling Pope’

Interview with Stefania Falasca, Vice-President of Foundation

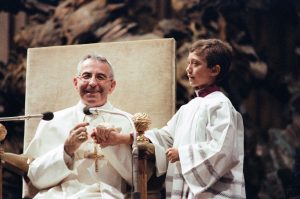

Pope John Paul I, Albino Luciani, died suddenly in his sleep at 65 in the late evening of September 28, 1978. The last Italian Pontiff was born in Canale D’Agordo in the Alps on October 17, 1912. The last words written in his agenda, where he wrote everything, were “that I may love You ever more.”

That agenda, full of notes written with minute calligraphy and a blank notepad are the only personal documents written by Albino Luciani during the 33 days of his pontificate. Given that they are such a precious source, the John Paul I Foundation, therefore, will soon transcribe and publish both of them, bringing together in one volume all the addresses and homilies of his pontificate. Not an accidental choice because, in fact, it was in the agendas, as he usually always did, that Luciani — the Patriarch of Venice elected Pope on Aug. 26, 1978 – stowed away the first drafts of homilies, addresses and publications.

One can easily see this documentation that, once studied, will be a precious source for historians of the Church of the 1900s, and for anyone who wants to know him better. But it will also serve to delineate again better the figure of Albino Luciani, already screened for his Cause of Beatification. The last stage reached was the proclamation of the heroic virtues of the Venerable John Paul I, on November 9, 2017. Now only one miracle is lacking, attributed to the intercession of John Paul I, to proclaim him Blessed.

For example, a few pages before the last annotations in black on white paper, words not spontaneously improvised are read, as it seemed, instead, at the Sept. 10, 1978, Angelus in Saint Peter’s Square. Perhaps they were the words of the smiling pontiff’s pontificate that remained most imprinted on the memory of many: “we are the object of timeless love on God’s part, who doesn’t want to do us any harm but only good…he is a father, rather a mother… “

In his little notepad, Luciani entrusted his thoughts on the duties proper to the Successor of Peter as well as small daily necessities. Along with to-do lists, one reads about his idea of drawing on the papal ring the venerated figure of Our Lady of Guadalupe or his concern about procuring a proper “barber” in Rome, since he no longer could use his Venetian one.

His pontificate, one of the briefest of the two-thousand-year history of the papacy, lasted just over a month. However, its importance, said later his successor St. Pope John Paul II, Karol Wojtyla, who came from Poland, is inversely proportioned to its duration. Therefore, a year ago Pope Francis instituted — with a solemn Rescriptum ex audientia sanctissimi” dated February 17, 2020, the John Paul I Vatican Foundation, which on April 28 celebrated officially its birthday. Its stated purpose, by Bergoglio’s will, is none other than “to enhance the value and diffusion of the knowledge of the thought, of the works and of the example of Pope John Paul I,” states the rescript itself.

The first year of the foundation’s activity was also conditioned by the pandemic. However, at least one important result was attained: the foundation acquired the entire private archive of Pope Luciani, now available and in order on the shelves of the two rooms on Via della Conciliazione 3, where the Foundation has its headquarters.

There are 64 binders containing manuscript sheets, papers, letters, printed material, photographs going back to the period between 1929 and 1978. It is a fundamental source of information to reflect further on the figure of the so-called “smiling Pope.”

The John Paul I Foundation has charged an archivist with the ordering and inventory of all the material, and all the most important documents are being digitalized. Once these two operations are completed, the idea is to give access to all scholars to this precious material, including files containing the school notebooks and notes of Albino Luciani, as a seminarian in the Gregorian Seminary of Belluno, where the future Pope showed he was a brilliant student.

The archive gets larger with the passing of time, and the different stages of Luciani’s biography: he was ordained priest in 1935. In 1937 he was Vice-Rector of the Gregorian of Belluno; in 1947 he obtained his degree in Theology from the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome. In 1958, when Luciani was Pro-Vicar General of the Diocese of Belluno, John XXIII appointed him Bishop of Vittorio Veneto. Between 1962 and 1965, Luciani took part in the works of Vatican Council II. In 1969 he became Patriarch of Venice and in 1973 Cardinal, until his election as Pontiff following St. Pope Paul VI’s death.

As to the importance those papers had for him, suffice it to say that in every move, until that to the Vatican, in the rooms of the Papal Apartments, the smiling Pope wanted to bring with him all his archive, to have everything at hand next to his desk.

Aside from enlightening about the Smiling Pontiff, the Foundation, to respond better to its institutional ends, promotes study, research and diffusion of the work and thought of the Pope whose name it bears. As of today, the Foundation also has a website, rich in images and content, with texts in Italian and English.

EXAUDI talked about Luciani’s private archive and the activities of the John Paul I Foundation with Stefania Falasca, Vice-President and Coordinator of the Foundation’s Scientific Committee.

***

EXAUDI: Dr Falasca, can you describe briefly the content of Pope Luciani’s private archive? What materials are included in it? And why is it important that the John Paul I Foundation acquire them?

STEFANIA FALASCA: It is a very rich collection of heterogeneous documentary material that spans half a century: from 1929 to September 28, 1978: autographed writings, notebooks, notes, agendas, printed and photographic materials, correspondence . . . A total of 64 folders, of notebooks with notes of lessons taken as a student at the Gregorian Seminary of Belluno up to the 66 agendas on his Episcopate from 1960 to 1978, among them the agenda in blue leatherette that he continued to use during the 34 days of his Pontificate, where his last written words are imprinted. They are the papers of a life, whose existence comes to be known only in the early 2000’s.

EXAUDI: And then what happened?

STEFANIA FALASCA: In 2007, when the Bishop of Belluno-Feltre decided on a supplementary for Luciani’s Cause of Canonization, I was the person made in charge of an Inquisitio, a reconnaissance of the private archive. Thus, in a first examination, the nature of the writings could be identified and reconstruct the genesis, the development and the complex course of this private archive, which from the Apostolic Palace of the Holy See, after the death of John Paul I on September 28, 1978, was returned to the patriarchal headquarters of Venice. Let’s say that it is primarily about a personal file cabinet from where interventions, lessons, conferences, homilies, articles and publications took shape.

EXAUDI: But are there writings containing more personal elements?

STEFANIA FALASCA: Although present exceptionally are also notes in diary form, as his participation in Vatican Council III or his private audience with John XXIII, on the occasion of his episcopal consecration. However, it seems that Luciani found strange the form of an intimate and private “diary.” Joined to the writings of the Archive, as an integral part of it, is also a furnished library. In the whole they functioned as a laboratory, in other words, as Luciani’s work office. Therefore, they are papers that tell a lot, as a whole and in individual parts, of the profile of the one who wrote and kept them. They are a privileged source to study the shaping of a thought and of a subject and his oscillations, in the many variants of the drafting of his interventions, and to understand the figure of Luciani in relation to the circumstances he lived and experienced. It is a ‘patrimony’ of the Foundation that is of fundamental importance also to carry out the project of the publication of the “Opera Omnia.”

EXAUDI: Is it true that Albino Luciani always wanted to take this material with him, in all his moves, even when going to Rome?

STEFANIA FALASCA: Yes, as I said this was his “work office,” a sort of open work in progress building site, indispensable for Luciani, from which he could continually draw and add. Even on the evening before he died, he was immersed in the “work office” of readings taking up his past interventions to prepare the General Audience. It was his modus operandi, which he was used to since he was a professor in the Seminary: to bring the work to be studied also to his bed and read it before falling asleep.

EXAUDI: What will be the next steps of the John Paul I Vatican Foundation? What initiatives are you planning?

STEFANIA FALASCA: In this first year, we have laid the basis to fulfil the purposes to which the Foundation aims. On March 1, 2021, under the guidance of the Prefect of the Vatican Apostolic Archive, Monsignor Sergio Pagano the inventory work began and, contemporaneously, the digitalization of the archive, with the collaboration of the Vatican Apostolic Library. Foreseen for the inventory is a period of six months. We have instituted study scholarships for this work and we will institute others.

EXAUDI: What do you expect afterward?

STEFANIA FALASCA: Once the cataloguing is finished, the Scientific Committee will establish the long-term work to be undertaken on the papers of the Archive, which must be transcribed and examined using the philological method, and the project to carry out the “Opera Omnia.” The critical edition of John Paul I’s teachings will soon be published, with the complete synopsis of his written and pronounced interventions as Pontiff and the transcriptions of the autographed agenda and personal note pads of his 34 days of pontificate. Then the critical edition will follow of the text of the “Illustrious” (the famous collection of “open letters” written by Luciani to personalities of history and of literature, published the first time by the Messaggero di Sant’Antonio between 1971 and 1975, ndr).

EXAUDI: You also talked about books of John Paul I’s private library . . .

STEFANIA FALASCA: Considering that the private archive was joined to the origin, as an integral part of it, as a furnished library, among the projects already approved by the Foundation there is also the reconstitution of Luciani’s personal library in Venice, in the diocesan library of the patriarchal seminary.

Speaking of books, I add also that for the series dedicated to John Paul I, started by the Foundation together with the Libreria Editrice Vaticana, the volume is about to be published in English and Spanish on Pope Luciani’s death (Italian title “Pope Luciani: Chronicle of a Death,” by Stefania Falasca, which came out in 2017, ndr), which with the historical-critical method, on the basis of the acquired procedural documentation, restores to the historical truth of the circumstances of Pope Luciani’s death. Finally, among the projects started and in the phase of proximate realization there is also the preparation of a congress on the teaching of John Paul I with works of the Scientific Committee planned for the spring of 2022.

Related

Despite hardships, Christianity is growing “astronomically” in northern Nigeria

Ayuda a la Iglesia Necesitada

10 April, 2025

3 min

“Christianity, a Powerful Engine of Social Transformation”

Exaudi Staff

09 April, 2025

3 min

Let God be God

Albert Cortina

11 March, 2025

25 min

Pope Francis spent a peaceful night

Exaudi Staff

02 March, 2025

1 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)