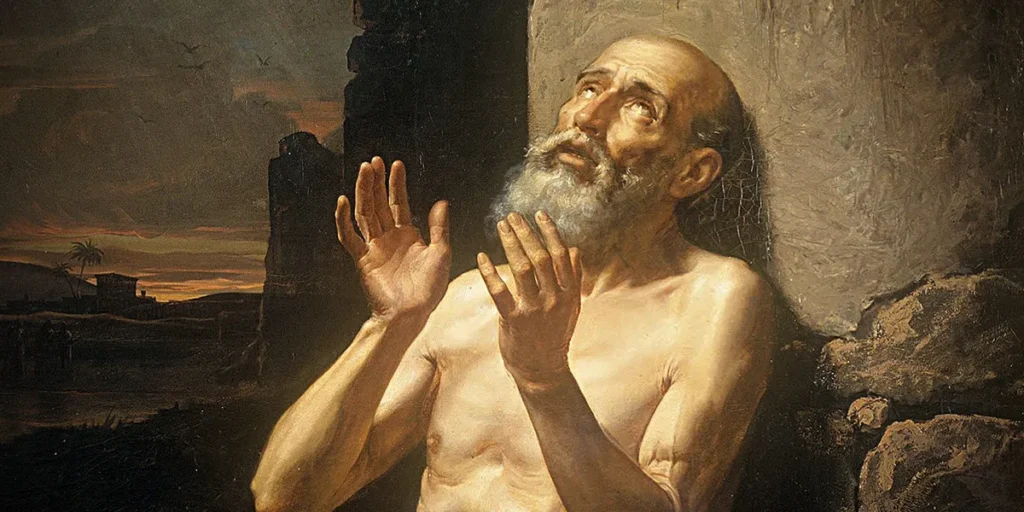

Job, the Mystery of Suffering

The Mystery of Suffering in the Light of Job and the Cross of Christ

“You, who are under trial,

you, afraid that

your shoulders may weaken,

that your shoulders may bow,

that the strength of your arms may fail,

that your hands may fall faint –

– Watch – it is a time of trial,

– Watch – it is the time of Job. –

you, trampled,

in the katorga, in the torment – you –

Jobs – Jobs –.” (Karol Wojtyla. Job; p. 269)

Suffering, tribulations, setbacks, our own and others’ tragedies, the injustices that cry out to heaven, are a mystery. We ask: Why? Why the suffering of the innocent? We immediately address these questions to God. Why, Lord, do you send us these trials? Days and centuries pass, and there is suffering in its many forms. Explaining it—what we call explaining it—is rather poor. The experience of suffering far exceeds attempts to clarify it in a few lines. Karol Wojtyla (1920-2005) wrote the play JOB in 1940 to soothe the souls of the suffering, the Jobs of our time, encouraging us to raise our gaze and enter into the history of Salvation, announced in the poem of the suffering servant. Forty-four years later, Saint John Paul II wrote the Apostolic Exhortation Salvifici doloris (1984). He returns to suffering, returns to Job, in a meditation whose seeds are found in his play of 1940.

We know the story of Job: he has lost everything. He says to God, “You have taken my oxen and my sheep, / You have taken my camels, my donkeys, / You have struck down my sons with Your whirlwind, / You have struck down my virgin daughters – / You have given, You have taken away –/ Yours is all, Yours is –/ Yours is the Will and Yours is the Power –/- Why do You still feed me -? (pp. 185-187)”. Job accepts God’s will, but he is overcome by grief; Bewildered, he rebukes God: “Have I sinned against my neighbor, / or as a judge, sitting in the gate, / abused my legal power -? / Have I oppressed the poor -? / Have I left any orphan in misery? – / Have I been hard-hearted? – / Have I been enraged by another man’s wife – / Or have I demanded – or taken anything away -? / Am I not allowed to cry out? / Why, Lord, is this in my life? – / Why do You burden so much on my weak shoulders? – / Why are you so merciless with me? – / Why do You bear Your wrath against me? – (Job, p. 205).” These are the complaints, born from pain, of someone who doesn’t understand why so much suffering occurs without any fault of his own.

His friends think they know the causes of Job’s misfortunes. It’s a simple logic: he has done something very wrong, and that’s why God is punishing him. They console him by telling him that he must be strong in his pain, because if he is as just as he says, he will obtain mercy, he will regain grace, and everything will be right again. This advice is on the level of a simple and direct rule of three. The words of his friends do not alleviate his pain, for Job insists on his innocence. The mystery of pain continues, and it is God himself who, at the end of the Book of Job, “rebukes his friends for their accusations and acknowledges that Job is not guilty. His is the suffering of an innocent man; it must be accepted as a mystery that man cannot fully understand with his intelligence.” The Book of Job does not distort the foundations of the transcendent moral order, founded on justice, as proposed by all Revelation in the Old and New Covenants. But, at the same time, the book clearly demonstrates that the principles of this order cannot be applied exclusively and superficially. If it is true that suffering has a meaning as punishment when it is linked to guilt, it is not true, on the contrary, that all suffering is a consequence of guilt and has the character of punishment. The figure of the righteous Job is an eloquent proof of this in the Old Testament (Salvifici doloris, no. 11).

The Book of Job says quite a bit, but it is not the last word of Revelation on suffering. It is the Passion of Christ that will shed light on our understanding of the suffering of the innocent. The young Wojtyla, in his play Job, proclaims this announcement through the mouth of Elihu: “And looking down the centuries, I see: ‘You have allowed / great suffering to this man, / although he was upright, although on his lips / there were no unworthy words — / I see – I see … You allow it / – the crowds drag the Just One and the common people howl, / the rabble tramples him – / behold, they are leading the Just One – / to the courts they lead him – You have allowed it …” Later, Elihu concludes: I see throughout the centuries – I announce it to you – / to you who suffer, who grieve, Jobs – / I raise my prophetic soul through the centuries, / From Suffering arises the New Law.” (Job, p. 263). And when body and soul waver, when it seems that one can no longer bear it, and there is no way to understand the present evil, Elihu insists: – Watch – it is a time of trial, / – Watch – it is the time of Job. – / you, trampled, / in torment – you – / Jobs – Jobs.” It is Christ who reveals to human beings the depths of their being.

We can make Wojtyla’s consideration our own and say that today, now, is also a time of trial, a time of torment, the time of Jobs. Along with the good things before us, there is also the present reality of our own suffering and that of so many others throughout the world. Nor is there any lack of unease that can come from seeing the barque of Peter flounder before the gales that shake its unity, holiness, catholicity, and apostolicity. It is certainly the time of Jobs.

The question about suffering continues to seek answers. Saint John Paul II responds: Christ suffers voluntarily and suffers innocently. He embraces with his suffering that question, posed many times by men, which has been expressed, in a certain sense, radically in the Book of Job. However, Christ not only carries with him the same question (…), but it also carries the maximum possible answer to this question. The answer emerges, one could say, from the very material from which the question is formed. Christ gives the answer to the question about suffering and its meaning not only with his teachings, that is, with the Good News, but above all with his own suffering (…). This is the final and concise word of this teaching: “The doctrine of the Cross,” as Saint Paul will one day say [Cf. 1 Cor 1:18] (Salvifici doloris, no. 18).

With our gaze raised to the Cross of Christ, our suffering becomes united with the Lord’s Passion. We cease to be a sorrowful verse scattered in the cosmos, but join the great poem of the suffering servant and the chain of love of the Good Samaritan, ready to alleviate the pain of our suffering neighbors with works of care and consolation. It is the Lord who sustains us to be Samaritans to our neighbors, even when we are tired and burdened.

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)