Is palliative sedation a good medical practice?

An ethical and necessary medical practice to alleviate suffering without hastening death

Does a terminally ill patient have the right to palliative sedation? Yes, as long as it is indicated, and when it is indicated and there is consent, the doctor must apply it. In this case, conscientious objection has no place, just as it would not be possible to object to any other correctly indicated treatment. Abusing sedation is as serious as not applying it when it is necessary for the patient.

You may be surprised by the title, but I have chosen it with full intention. Sometimes palliative sedation is not used as a good medical practice. However, it will be you, dear reader, who at the end of this article will be able to assess whether this treatment is a good medical practice or not.

All doctors should take into account what our Code of Medical Ethics says in article 38.5: “Palliative sedation in terminally ill patients is a correct and indicated treatment when there are refractory symptoms that cannot be controlled with available treatments. To perform it, the explicit or implicit consent of the patient must be obtained […].

In our professional activity, we see that there are patients who have at some point in the evolution of their illness one or more symptoms that are refractory to the treatment they are receiving and that cause unbearable suffering. In this situation, we should reduce the patient’s consciousness to guarantee a peaceful death, without suffering.

However, the need to reduce the consciousness of a patient in the days or hours before their death has been and is the subject of controversy, both in its clinical, ethical, legal and religious aspects. Today there are still confusing ideas, in society and in our profession, about palliative sedation. Furthermore, those who are not familiar with the indications and technique of sedation or who lack experience in palliative medicine may mistake it for a covert form of euthanasia.

We must bear in mind that sedation, in itself, is a neutral therapeutic resource, and therefore ethically neutral. It is the goal we seek with sedation that is the measure to assess the act as ethical or not. Sedation should not be instituted as “slow euthanasia” or as “covert euthanasia”; this would be bad medical practice. The doctor is obliged to sedate only up to the level required to relieve refractory symptoms. The use of palliative sedation is acceptable as long as an appropriate adjustment of drug doses is maintained. If the dose of sedative exceeds that necessary to achieve symptom relief, there would be reason to suspect that the purpose of the treatment is not to relieve the patient, but to hasten his death. That is why the dose we should use is the one indicated by symptom control, because an insufficient dose would prolong unnecessary suffering during the dying process, and an overdose would cause death.

It is worth remembering that there is a clear and relevant difference between palliative sedation and euthanasia if observed from the perspective of Ethics and Medical Deontology. The border between the two is found in the intention, in the procedure, and in the result. Sedation seeks to reduce the level of consciousness, with the minimum necessary dose of drugs, to prevent the patient from perceiving the refractory symptom. In euthanasia, early death is deliberately sought after the administration of drugs at lethal doses, to end the patient’s suffering.

Today, in truly human medicine, there is no place for therapeutic incompetence in the face of terminal suffering, whether it takes the form of inadequate treatments due to insufficient or excessive doses, or abandonment. In the face of refractory suffering in patients, it is the physician’s ethical duty to decisively address palliative sedation, even when this treatment could result, as a side effect, in an undesired anticipation of death.

For the patient, sedation implies a decision of profound anthropological significance: that of renouncing the conscious experience of one’s own death. For the family, it also entails important psychological and emotional effects. This is why such a decision cannot be taken lightly by the healthcare team, but must be the result of careful deliberation among all and a shared reflection on the need to reduce the patient’s level of consciousness as the most appropriate therapeutic strategy at that time.

Does a terminally ill patient have the right to palliative sedation? Yes, as long as it is indicated, and when it is indicated and there is consent, the doctor has the obligation to apply it. In this case, conscientious objection has no place, just as it would not be possible to object to any other correctly indicated treatment. Abusing sedation is just as serious as not applying it when it is necessary for the patient.

When the doctor sedates a patient who is suffering in the terminal phase and does so with clinical and ethical criteria, he is not causing his death; he is preventing him from suffering while he dies; he is carrying out good medical practice.

Dr. Jacinto Bátiz Cantera – Director of the Institute for Better Care – San Juan de Dios Hospital in Santurce

*Article published in http://www.medicosypacientes.com

Related

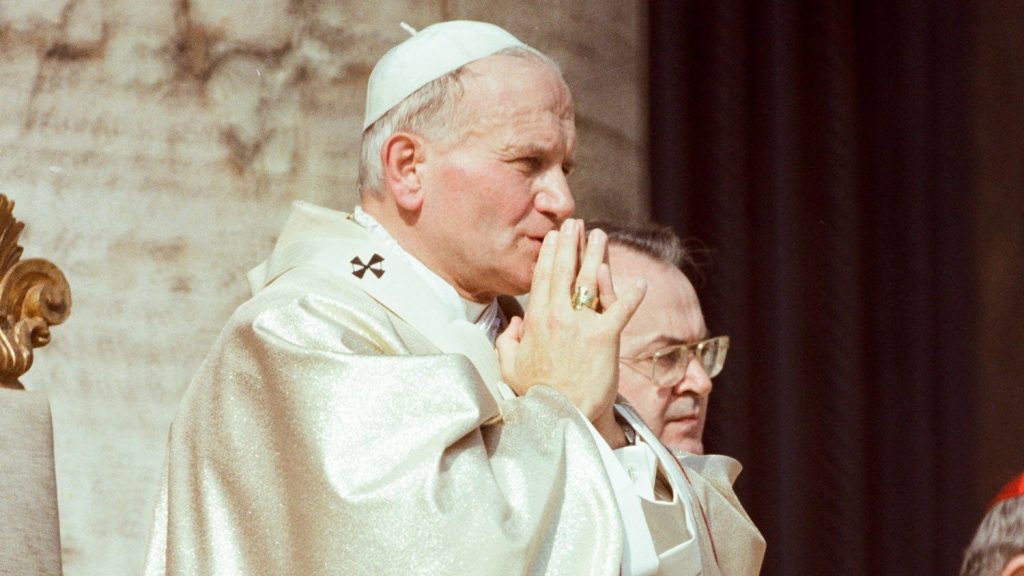

Being for Others: Saint John Paul II’s Vision of the Gift in Creation and Human Relations

Francisco Bobadilla

23 February, 2026

3 min

When Retreat Becomes Creation

Exaudi Staff

23 February, 2026

3 min

Domine, ¿Quo Vadis?

Rosa Montenegro

23 February, 2026

4 min

The Economy of Women’s Impact

Exaudi Staff

20 February, 2026

3 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)