INTERVIEW: Growing Consensus: Newman to Be Doctor of the Church

Expert & Scholar, Dr Paul Shrimpton, Shares Latest Findings Following Cutting-edge Research

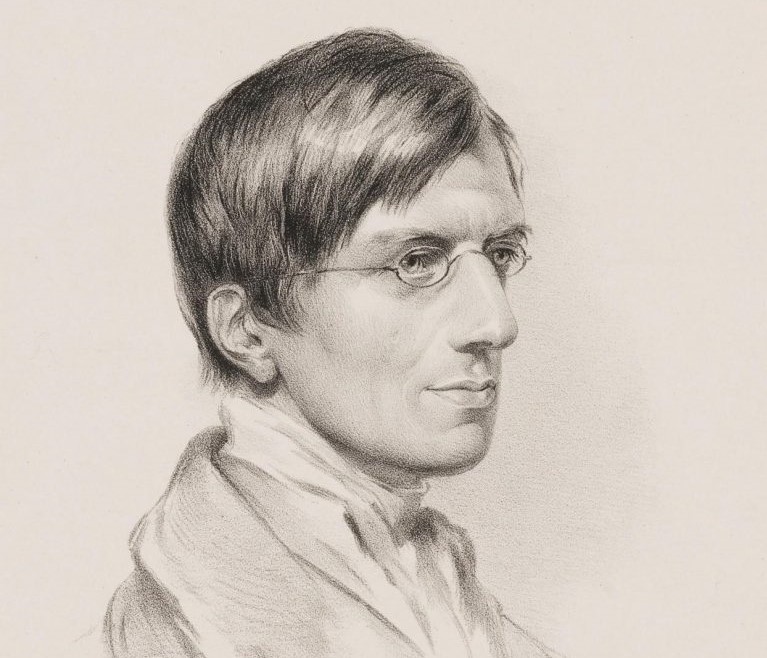

There is a growing consensus that one day St. John Henry Newman will be a Doctor of the Church.

Newman expert and scholar, Dr. Paul Shrimpton, made this affirmation in an exclusive interview with Exaudi, on the basis of his cutting-edge research.

Dr Shrimpton recently published the critical edition of Newman’s university papers, My Campaign in Ireland, Part I. This has not published before and so provides precious new material for Newman scholars.

He explains about Newman’s educational genius, further revealed through this endeavor, and why people of faith and of no faith seem to be fascinated by Newman.

Shrimpton, who since the canonization of St John Henry in October 2019, has been running a Newman reading group for graduate students at Oxford University, speaks about Newman’s relevance today, and reflects: “There is the ring of truth in all that Newman writes on education – and truth inspires. It inspires me and it inspires others.”

Here is the scholar’s interview with Exaudi:

***

EXAUDI: Dr. Shrimpton, I would like to ask you about your recently-published critical edition of Newman’s university papers, My Campaign in Ireland, Part I. Since these have never been properly published before, would it be fair to say this volume represents something new in the world of Newman scholarship? And how so?

SHRIMPTON: For reasons which I explain in my editor’s introduction, these papers were only ‘printed for private circulation’ in 1896, six years after Newman died. They have never been published before, though facsimile reproductions have been made and extensively used by Newman scholars. The text for this critical edition has been completely re-set, allowing my footnotes to appear beneath Newman’s text, while respecting the format and page layout of the original version. This has enabled me to provide comprehensive footnotes which elucidate the significance of the volume’s various documents by providing a historical context for Newman’s educational endeavors in Dublin.

EXAUDI: What can one expect to learn that has not been previously known about this great saint?

SHRIMPTON: Newman’s fame in education is due almost entirely to his educational classic, The Idea of a University, which is regarded by many as the greatest book there is on the nature and purpose of a university. But few people realize that he set up the second Catholic university in modern times – and almost singlehandedly. The university reports in My Campaign show how he went about this task and the way in which he was able to turn theory into practice. It is clear from reading them that we are dealing not with an academic administrator who is far removed from students, but someone who has a deep understanding of the human condition and manages to unify the many strands that go to foster human flourishing at university.

This is the reason why all those with a stake in higher education should take note of what Newman does in setting up the Catholic University in Dublin, which, after a complicated history, became University College Dublin, the second largest university in Ireland.

EXAUDI: How do these papers give insight, if you will, into Newman’s educational genius?

SHRIMPTON: There are all sort of insights in these university papers. For example, the lengthy Rules and Regulations that Newman devised include wonderfully inspiring passages on how a university should set the right tone in dealing with its students: the backward, the lazy, as well as the highly motivated. In writing this, Newman drew on his experience as a tutor at Oriel College, Oxford. He grasped the need for a gradation of liberties as the young person approached adulthood – what might be termed a progressive ‘education in freedom’ – through the right mixture of liberty and restraint.

Many readers of the Idea praise it for its splendid prose and idealism, but dismiss it as unapplicable to the modern world; they assume Newman is a pure theorist. Others assume Newman was only interested in the humanities. These and other assumptions are blown apart when one reads My Campaign, as we see we see a workable scheme for a modern university that provides for science and medicine alongside Latin and Greek. Newman seeks to achieve a balance between protecting the initial years for a liberal education and some degree of specialization in line with future professional studies; preparing those soon to be engaged in the business of life, yet without sacrificing the definiteness and completeness of the academic system or its demands for those to whom knowledge itself is a profession.

A bonus in this volume is Discourse V, the ‘missing’ discourse from the Idea of a University. In the words of the leading Newman scholar Ian Ker, Discourse V ‘provides a devastating contrast between modern fragmented secularist education and an integrated liberal education in the Christian tradition, and is therefore one of the most eloquent parts of the Discourses’. This discourse has inspired, among other, leading intellectuals such as Alasdair McIntyre.

EXAUDI: What motivated you to start this endeavor? How would you briefly explain this works?

SHRIMPTON: I was approached by my publisher, Tom Longford, at a launch of two volumes that are part of the Gracewing Millennial Series of critical editions of Newman’s main works. He suggested that the unpublished My Campaign could form part of this series and proposed that I should undertake the editing, knowing that I had recently published with Gracewing The ‘Making of Men’: the Idea and Reality of Newman’s University in Oxford and Dublin (2014). I was delighted and honored to take this on. I had spent nine years researching for and writing this book, so was well prepared for the task of editing My Campaign.

EXAUDI: What, as an expert in Newman, would you say is his relevance to today?

SHRIMPTON: I have spent all my working life – four decades – in education, and can truly say that there is no-one to compare with Newman for his insights into education. In so many ways his ideas provide a powerful antidote to various shortcomings in schools and universities today, whether it be with the need for an education in virtue as well as the intellect, the importance of personal influence – Cor ad Cor Loquitur (Heart Speaks to Heart) – and individual attention in the process of maturation, understanding the role of social education and how it operates, not to mention a host of insights that Newman develops in the Idea itself.

Reading Newman is not easy, not least because he constantly challenges and even overwhelms the reader with ideas. But if the language is ornate – and he is regarded by some as the finest prose writer of the nineteenth century – the rewards are plentiful.

Newman saw the beginning of post-Enlightenment times, when rationalist ideas were already working their way into society and the university; and it is remarkable how observant he was about contemporary trends and how accurate in his diagnosis of educational policies which distorted the true nature of education. The historian Christopher Dawson comments that ‘Newman was the first Christian thinker in the English-speaking world who fully realized the nature of modern secularism and the enormous change which was already in the process of development, although a century had still to pass before it was to produce its full harvest of destruction.’

What is astonishing is that people of no faith, as well as those of faith, are fascinated by Newman.

EXAUDI: Why do you believe this is?

SHRIMPTON: The reason is that he provides a much-needed educational vision for today, for it is generally recognized that his educational writings provide an attractive alternative to the shapeless, relativistic and uninspiring alternatives of contemporary universities. The concept of a university as an institution of unique purpose has all but dissolved, and contemporary universities increasingly function as performance-oriented, heavily bureaucratic, entrepreneurial organizations committed to a narrowly economic conception of human excellence. Recent literature which draws attention to and explores the loss of direction at the modern university is indicative of a loss of a coherent vision. In attempting to recover a sense of purpose, several of these modern critiques use the Idea as a key point of reference, and some use Newman as the pivotal figure in their analysis. It is unsurprising that his educational vision, with the pastoral idea at its root, is an ideal foil to the schemes of modern-day planners, since the bureaucratic is disinterested in caritas, the engine of true education.

EXAUDI: What was your greatest challenge in engaging in this project? And what enabled you to push past it?

SHRIMPTON: Surprisingly perhaps, I would have to admit that my greatest challenge was to translate ten or so pages of Latin into English, such as the letters from Rome to the Irish bishops about the University and the decrees of the Dublin synod of bishops in 1854 setting up the University. While educated people in the nineteenth century would have been able to read Latin prose, this is no longer the case!

I should also add that I have been anxious at times in dealing with this great Christian humanist not to misrepresent him or distort his thinking in any way. Besides taking all the human measures to ensure that I don’t mislead readers, I have also developed the habit of praying to him for help in my work of research and writing on him.

EXAUDI: How does Newman personally inspire you? And how do you believe, learning more about him through your work, others will be similarly inspired?

SHRIMPTON: There is the ring of truth in all that Newman writes on education – and truth inspires. It inspires me and it inspires others.

Since the canonization of St John Henry in October 2019, I have been running a Newman reading group for graduate students at Oxford University. I send out the reading material a week in advance, and then we meet to discuss it for an hour. We met weekly for the first two months, then fortnightly; then the meetings went online when we entered ‘lockdown’. Far from collapsing, the reading group grew as students joined from Harvard, Princeton, Cambridge and Leiden (Holland). After reading through the whole of the Idea, we tackled some of the university sketches in Historical Sketches vol. iii, then the Tamworth Reading Room letters to The Times in 1841, and now we are reading sections of Newman’s first novel Loss and Gain, which is set in Oxford. The reading group has exceeded my expectations: the students are enthralled with Newman and each fortnight they come back for more.

EXAUDI: How can one access this or buy this volume?

SHRIMPTON: My Campaign in Ireland, Part I (pp. xli + 614, hbk) is published by Gracewing and at £35 is affordable by individuals and not just libraries.

EXAUDI: Is there a reason why the title says Part I? Is there a Part II?

SHRIMPTON: Nine months ago, on a visit to the Newman archive in Birmingham I discovered that two documents were earmarked for Part II: a long memorandum (172 pages) entitled ‘My Connection with the Catholic University’, which was published in 1956; and an appendix to it (657 pages in length) which has never been published – all in Newman’s hand! I have also discovered the first draft of the memorandum (156 pages), which not been published. I am undertaking a critical edition of all this material, and the volume will hopefully appear around Easter 2022.

EXAUDI: Has interest in Newman and his educational ideas grown since his canonization?

SHRIMPTON: Yes, it seems clear to me that interest in Newman has grown, though like everything else this interest has been tempered by Covid and its ramifications. I would add that there seems to be a growing consensus that one day Newman will be recognized as a Doctor of the Church.

Related

Despite hardships, Christianity is growing “astronomically” in northern Nigeria

Ayuda a la Iglesia Necesitada

10 April, 2025

3 min

“Christianity, a Powerful Engine of Social Transformation”

Exaudi Staff

09 April, 2025

3 min

Let God be God

Albert Cortina

11 March, 2025

25 min

Fernando Puig, new rector of Santa Croce

Fundación CARF

19 February, 2025

6 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)