Historicity of the Virgin of Guadalupe

Four points of support: historical, archaeological, scientific, and sociological

For the historically uninitiated, it may come as a surprise that there is any doubt about the historicity of the apparitions of the Virgin of Guadalupe. In fact, it is the most visited religious shrine in the world (even more than St. Peter’s in the Vatican or Mecca in Saudi Arabia). However, just as other Catholic religious shrines arouse historical suspicions – such as Santiago de Compostela or the Virgin of Pilar – so does the much more recent Virgin of Guadalupe.

One should not think that those who doubt the apparitions are furious secularists, belligerent atheists, or fanatical evangelicals. Doubts, over the centuries, have been sustained by such people, but also by pious priests, religious, fervent Catholics, non-religious scholars, and by the last Abbot of the Basilica of Guadalupe, Guillermo Schulenburg Prado. To make a brief list, we can mention the following:

- 16th century: Fray Bernardino de Sahagún and Fray Francisco de Bustamante (both Franciscans).

- 18th century: Juan Bautista Muñoz and Fray Servando Teresa de Mier (Dominican).

- 19th century: Joaquín García Icazbalceta.

- 20th century: Edmundo O’Gorman, Fr Stafford Poole C.M. (Congregation of the Mission of St Vincent de Paul), Richard Nebel, Fr Guillermo Schulenburg Prado, and Fr Carlos Warnholtz Bustillos, the latter two, Rector and Archpriest of the Basilica of Guadalupe respectively.

- 21st century: Gisela von Wobeser.

Why do people doubt the historicity of the apparitions of the Virgin of Guadalupe? It would be pretentious to seek to settle in this short article the centuries-long dispute between apparitionist and anti-apparitionist authors. But perhaps the most consistent historical doubt is based on the fact that no mention of the event is preserved in the epistolary of Fray Juan de Zumárraga, a Franciscan, who was the first bishop of Mexico and before whom the miracle of the printing of the tilma of Saint Juan Diego with the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe was verified. It would have been logical, if the event had been verified, that he would have lacked the time to report it to the civil and ecclesiastical authorities of the time, and that documents of the miracle would have remained in the archives of the archbishopric of Mexico. But no, there are none. Neither is the baptismal certificate of Saint Juan Diego preserved, nor his remains, nor is it known where he was buried. With these historical gaps, one does not need bad faith to doubt the historicity of the apparitions.

What can be said about it? Let us say that the argument in favour of the reality of the apparitions of the Virgin of Guadalupe has four points of support: historical, archaeological, scientific, and sociological.

Historically speaking, how can we explain the silence of Fray Juan de Zumárraga? Well, by noting how, corporately, the Franciscans opposed the veracity of the apparitions throughout the 16th century. Led by Fray Bernardino de Sahagún – perhaps the person who knew the Mexican traditions best in his time – they thought it was a case of syncretism. Simply put, the Indians wanted to restore the cult of Tonantzin – who had a temple on the hill of Tepeyac, the site of the apparitions – mother of the gods. For Sahagún, the Indians simply wanted to return to their pagan cults, camouflaged as Marian devotion. On the other hand, the Dominicans, led by the second archbishop of Mexico, Alonso de Montufar, would promote this devotion in the 16th century. Let us say that, analogously to St. Thomas’ doubts about the resurrection of Jesus Christ, the Franciscans’ doubt does us more good than their credulity. Why? Because the belief – spread by evangelical and secularist groups – that it was an invention of the religious authorities of the time to attract the indigenous people to the Catholic faith is dismantled at its roots. This hypothesis does not hold water, since Sahagún goes so far as to call the Virgin of Guadalupe a “diabolical superstition”. From the 17th century onwards, the Franciscans accepted the reality of the apparitions.

Archaeologically speaking, its authenticity is confirmed by the discoveries made about the Nahuatl culture in the 20th century. In 1945, the American anthropologist Helen Behrens described the tilma of Guadalupe as a “swarm of symbols”. Archaeologists and anthropologists have sufficiently argued that, in reality, the Guadalupan cloak represents an authentic pre-Hispanic codex, loaded with symbols that only the indigenous people could interpret. In other words, the Spanish evangelisers had no idea what the Guadalupan mantle represented for the Indians. They only perceived its effects, but for the indigenous people, the symbols contained in the Guadalupan codex, printed on the tilma of Saint Juan Diego, represented a continuity and not a rupture with their ancient traditions. The image spoke to them in their own language, in their own mental categories. That is why St John Paul II recognised that the Virgin of Guadalupe was the perfect example of the inculturation of the Gospel: of how the Gospel becomes culture, so that it is not something foreign, alien or colonising, but something of their own.

Sociologically speaking, the proof is – and it is a sufficiently substantiated historical fact – in the mass conversions that, from 1531, the date of the apparitions, took place in Mexico. It is a documented fact that the first 10 years of evangelisation (1521-1531) produced rather meagre results. On the other hand, after Guadalupe, the archbishop himself had to ask the Pope for permission to perform mass baptisms, documenting the conversion, in a few years, of millions of indigenous people. This sociological reality can still be seen today in the Guadalupe Shrine, where the simple faith of the people continues to claim its authenticity.

Finally, there is scientific proof of the supernatural origin of the image. Proofs that were only consolidated until the 20th century. Although already at the end of the 18th century three copies of the Image of Guadalupe were made, on the same material on which it is made – agave popotule palm – to see how long they would last. None lasted more than 20 years. The original Tilma, on the other hand, spent 116 years outdoors, exposed to the humidity of Lake Mexico, the smoke of the candles and the kisses of the indigenous people. It withstood an accident in which acid fell on it in the 18th century and, even more portentously, it withstood the attack of 14 November 1921, when Luciano Pérez Carpio, a worker in the Private Secretariat of the Presidency of the Republic, placed dynamite in front of the sacred Image, by direct order of the President – these were times of religious persecution in Mexico – leaving the tilma intact, while bending the altar cross and the candelabra, all made of bronze.

More impressive are the discoveries that have been made throughout the 20th century by analysing the eyes of the image. To summarise these findings in a nutshell, it can be considered solidly proven that: the eyes appear to be alive, i.e. like a living human eye, in particular the “Purkinje-Sanson effect” is observed, according to which up to four images of what the eye is looking at can be seen reflected in the eye. Obviously, this is on a millimetre scale, which is impossible to achieve with the pictorial techniques of the 16th century, or even today, without the aid of a computer. Furthermore, by enlarging the images of the Virgin’s eyes more than 2000 times, the Peruvian researcher José Aste Tönsmann discovered up to 13 characters engraved on them. Some of them can be historically documented: Juan Diego himself, Fray Juan de Zumárraga, his translator and a black female slave that the Basque bishop brought with him. Obviously, all these images, which are present on the tilma, constitute a humanly inexplicable finding, which allows us to affirm, without fear of doubt, their supernatural origin.

Related

Miserando atque eligendo: The Legacy of Mercy in the Church

Luis Herrera Campo

28 April, 2025

3 min

A Meeting of Hope in St. Peter’s Basilica: Trump and Zelensky

Exaudi Staff

27 April, 2025

2 min

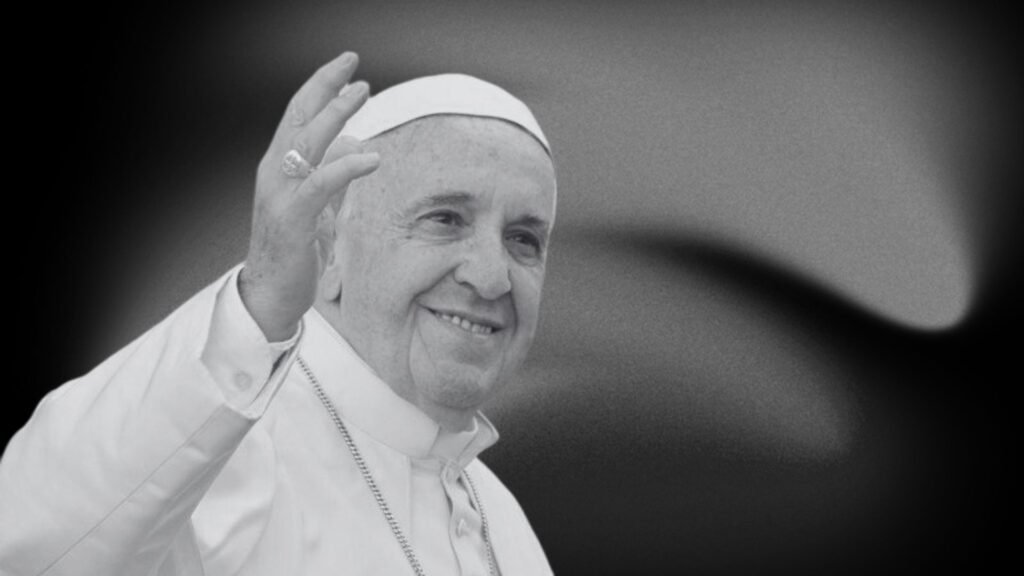

Saying Goodbye to Francis

Exaudi Staff

26 April, 2025

2 min

The Family: A School of Love, Forgiveness, and Hope

Laetare

25 April, 2025

3 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)