From May 68 to Woke Culture

A holistic view of the cultural revolution of May 68 and its influence on contemporary woke culture

I return to May 68 when I find interesting readings that help me understand it. I have made several comments about it on this blog. This is the essay From May 68 to Woke Culture (Palabra, 2024) by Pablo Pérez López, a professor of Contemporary History specializing in cultural history, and it shows. It is an ambitious vision oriented to give a holistic view of this stellar moment of Western culture (USA and Europe, mainly). The selection of causes that the author sets out to understand the roots of this revolution has been appealing to me. It also seems that the author’s proposal wishes to give an account of the current situation of Western culture, taking into account it before and after May 68. Perhaps too much.

May 68 has its antecedents in the American cultural intelligentsia, which led to The Free Speech Movement in 1964, whose cradle is at the University of California. The passionate force of Mario Servio, a student at the university, the singer Joan Baez performing We Shall Overcome, the proposals for freedom of political expression within the university, the first occupations of its premises with “sit-ins”, demonstrations for civil rights, sexual liberalization, were expressions of protest in an economically satisfied society, whose characters manifested a light, broad-spectrum socialist leftist orientation.

The leap to the University of La Sorbonne (first in Nanterre) in May 68 radicalized the movement, always in the hands of the university students who were joined by workers’ unions, political parties, intellectuals. From playful slogans (“Let us be realistic, let us demand the impossible”, “power has taken power, let us take power”) they moved on to barricades, giving rise to a political crisis in France, the management and outcome of which was carried out by President Charles de Gaulle, to whose figure and dealings the author of the essay devotes a good deal of space.

The allusion that Pérez makes to Chesterton, Ortega y Gasset and Huxley – intellectuals of the first half of the 20th century – who foresaw what May 1968 would bring is suggestive: changes in lifestyles rather than political transformations. As Huxley sensed, it was necessary to find a structure that would maintain stability in a society in which there was no law other than one’s own whim and in which the immediate satisfaction of pleasures was the only vital horizon (p. 105). Alasdair MacIntyre states it in similar terms when referring to the emotivism and functionalism of contemporary society. The emotion for the private world and the function for the anonymous mechanisms of society. An empty shell, pure political structure, and inside the libertarian spirit of May 68.

Benedict XVI referred to May 68 in a 2019 essay, pointing it out as one of the cultural milestones that has led to sexual scandals within the Church. Pérez López also comments on the legacy of May 68 in the field of sexual relations. A liberalization that had the pill as a great catalyst to separate sexual pleasure from reproduction. This invention facilitated the emergence of sexual expressionism in future generations: sex without responsibility. In the US, all the various manifestations of these libertarian practices were legalized through the right to privacy, which included abortion until the recent annulment of the Roe vs. Wade ruling, which leaves legislation on this matter to the discretion of each State.

I think that this libertarian humus formed by May 68 is at the root of the current libertarian emotivism: I want, I can, I don’t harm others, therefore I do it. And here a lot comes into play: unilateral divorce, weakening of social ties, absolute disposition of the rights of the personality (freedom, life, honor, image, privacy). A libertarian emotivism that can even go so far as to consider the body as a mere shell, totally available, subject to any whim of desire. A kind of new Gnosticism implicit in the positions of some activists of multiple identities. In this sense, Pérez López is right in considering the woke, with quite a bit of noise in the Northern Hemisphere, as a sequel to May 68. This movement – virulent in many of its manifestations – condemns in order to affirm itself. It seems – says Pérez López – that it is not enough to do what one wants, it is necessary that others recognize it as legitimate or good (…). They need to be publicly acknowledged that they are bad and those who do them are bad. They should be erased from the world of the possible (pp. 172-173). In the woke world, the grievance grows disproportionately behind the backs of truth, dialogue and freedom of conscience, thought and expression.

We are not a boat adrift culturally. There are furrows of good sowing. The creative force of freedom is capable of opening new furrows in reality with its own grammar full of truth, goodness and beauty. Moving forward, correcting course, yearning for a better future is an endless task. Cancellation is acidic, corrosive. We need, rather, to open constructive alternatives for this task of making the common life of human beings viable.

Related

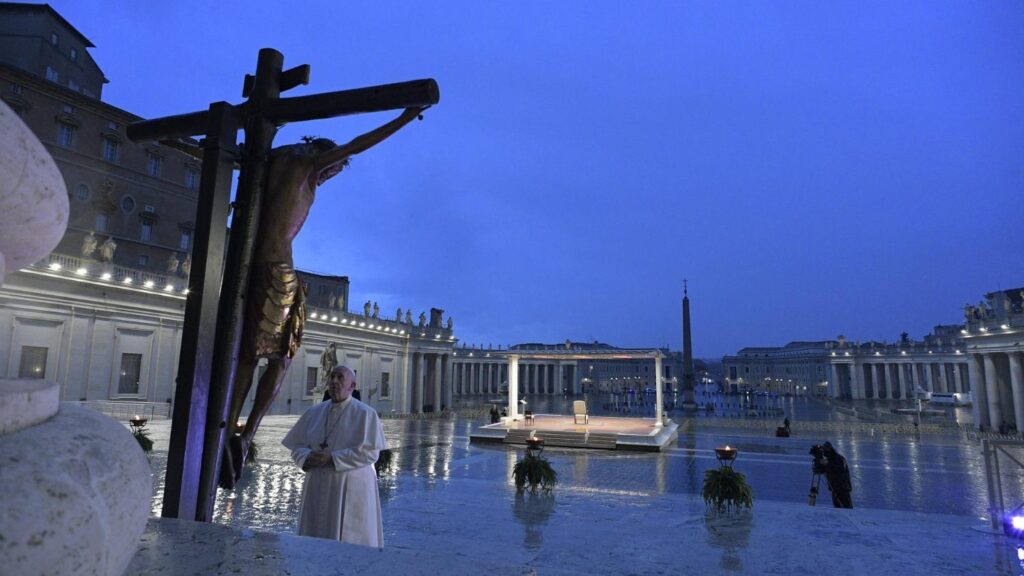

Francis. The Human and Religious Imprint of a Papacy

Isabel Orellana

24 April, 2025

5 min

Cardinal Felipe Arizmendi: With the Risen Christ, There Is Hope

Felipe Arizmendi

24 April, 2025

6 min

You Didn’t Give Up

Exaudi Staff

23 April, 2025

2 min

Sing, pray, give thanks

Mar Dorrio

23 April, 2025

2 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)