First Diabetic Woman Regains Autonomy: Success in Stem Cell Transplant

For the first time, a diabetic woman leads a normal life after a stem cell transplant

Not even three months after a 25-year-old woman with type 1 diabetes had received a transplant of reprogrammed stem cells, she began to produce her insulin. She is the first person to receive this treatment with cells extracted from her body. “Now I can eat sugar. I enjoy eating everything, especially stew,” said the woman, who lives in Tianjin (China), a little over a year after the transplant. The phase 1 clinical trial was carried out using induced pluripotent cells, which theoretically do not cause immune rejection. “They have completely reversed diabetes in the patient, who needed substantial amounts of insulin before the operation,” says James Saphiro, transplant surgeon and researcher at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada.

This discovery, which is a world first, follows the work carried out by a research group in Shanghai, China. These scientists announced the transplant last April of insulin-producing islets into the liver of a 59-year-old man with type 2 diabetes. In this case, reprogrammed stem cells from the patient were also used, and the result was successful, as he no longer needs insulin.

Around 500 million people suffer from diabetes in the world. Type 1 diabetes has the characteristic that the islets that produce it are attacked by the immune system. Type 2 diabetes is the most common; in this type, the body does not produce the necessary insulin or has a lower capacity to use it. One way to treat this disease is to transplant insulin-producing islets, but the difficulty lies in the shortage of donors and the need to administer immunosuppressants to prevent rejection in recipients. As is known, pluripotent stem cells could be cultured indefinitely and give rise to any tissue, so they constitute an unlimited source of the tissue necessary to produce insulin, such as pancreatic islets. If the cells used are also from the same person to whom they are to be administered, the use of immunosuppressive drugs could be avoided.

Deng Hongkui, a cell biologist at Peking University, and his colleagues used cells from three people with type 1 diabetes and brought them to a pluripotent state to obtain the necessary cell type. The technique discovered by S. Yamanaka in 2006 was modified by Deng, who changed the genes that produced the necessary transcription factors for small molecules. In this way, they obtained three-dimensional groups of islets and tested the safety and efficacy of these in mice and non-human primates. Later, in June 2023, they inoculated approximately 1.5 million islets into the woman’s abdominal muscles. This procedure was carried out in less than half an hour. The advantage of transferring the islets to the abdomen is that it allows the cells to be observed with the aid of magnetic resonance imaging. Until now, islets have been injected into the liver, but they cannot be monitored there. After 75 days, the patient did not need to take insulin and has continued to do so for over a year, without experiencing the ups and downs of blood glucose that are typical of a person with diabetes mellitus. Daisuke Yabe, a diabetes researcher at Kyoto University, said: “It is extraordinary. If this can be applied to other patients, it will be wonderful.” In turn, Jay Skyler, an endocrinologist at the University of Miami, Florida, who studies type 1 diabetes, said that these results make him think, but he believes that to declare this woman cured, it would be necessary to wait five years during which adequate insulin levels were maintained. As for Deng, he says that the effects seen in two other participants are also “very positive” because they will be celebrating their first anniversary in November, and he hopes to increase the number of participants, including between 10 and 20 more people.

It should be noted that this woman had previously received a liver transplant and was therefore receiving immunosuppressive drugs. Due to this circumstance, it was not possible to determine whether working with iPS cells reduced the risk of rejection of the pancreatic islets. In any case, it is necessary to bear in mind that, although there is no rejection of the graft because the cells are from the same recipient, in people who suffer from type 1 diabetes, as this is an autoimmune disease, it is always possible that the body itself attacks the transferred cells. Although Deng assures that, due to immunosuppressants, this has not been proven in the patient, they are continuing to work on the possible obtaining of cells that could overcome this reaction typical of this type of disease.

Autologous transplants have positive aspects. However, the possibility of extending them to the majority of people is complicated. For this reason, scientists have begun work with cells from other individuals and, from them, obtain the necessary islets.

Vertex Pharmaceuticals in Boston, Massachusetts, conducted a clinical trial with patients with type 1 diabetes. In this study, about 12 participants were treated with islets obtained from embryonic stem cells. The cells were inoculated into the liver and the patients were given immunosuppressants. Although all participants produced insulin when their blood contained glucose, only some were able to do without external insulin inoculation. Vertex is currently conducting a trial with islets derived from stem cells that have been protected from possible attack by the immune system by a mechanism. This work is being carried out with patients with type 1 diabetes and seeks to enroll 17 participants.

Yabe will also conduct a clinical trial in early 2025 with donated cells from iPSc to obtain islets and place them in the abdomen of three participants who are suffering from type 1 diabetes, who will be given immunosuppressants.

It is still excellent news that a possible treatment for type 1 diabetes has been achieved. However, the studies are still in their initial stages, so we will have to wait for these first advances to be confirmed, both in terms of safety and effectiveness.

Regarding the ethical aspect, it is important to highlight the origin of the cells in the first clinical trial to which we referred. These are cells reprogrammed from somatic cells and which become pluripotent cells. From them, we can obtain any type of cell, and this facilitates obtaining the islets of Langerhans that produce the necessary insulin. This procedure does not present any ethical objection, so it is highly recommended and should be promoted.

However, in other works to which we have referred, the use of embryonic stem cells is used. This has an ethically objectionable qualification, because, as we know, to obtain embryonic cells the human embryo from which they come must be destroyed. Eliminating a human embryo is ending a human being in its first stages of development. It is not a human being in potential, but in action, although all its potential has not yet been realized. It is not understandable that we continue trying to work with this type of cells, when we have a perfectly valid alternative that has proven to be effective, and that, since they come from the same individual, it is highly probable that they will not suffer an attack by the immune system.

Related

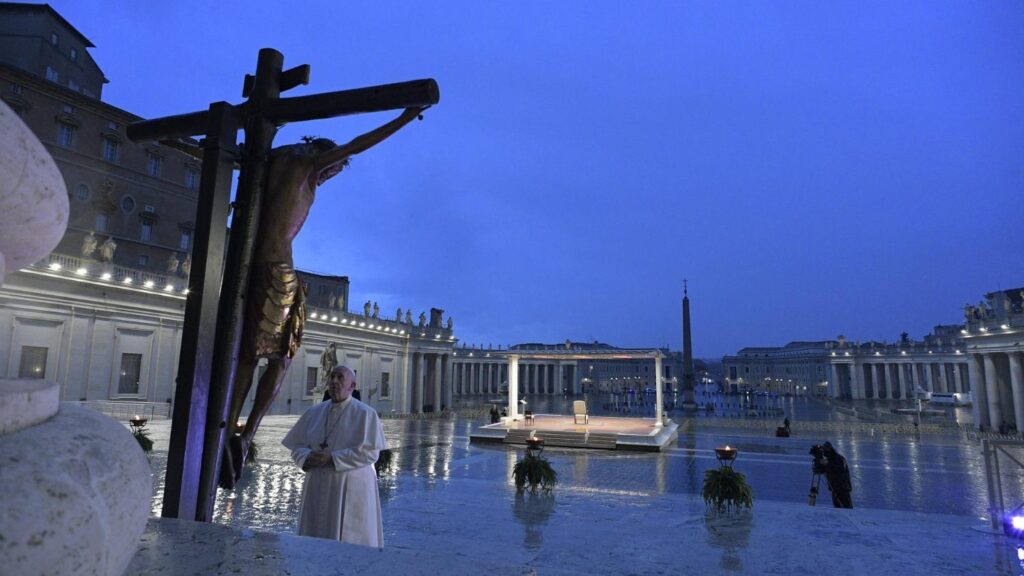

His Hope Does Not Die!

Mario J. Paredes

24 April, 2025

6 min

The Religious Writer with a Fighting Heart

Francisco Bobadilla

24 April, 2025

4 min

Francis. The Human and Religious Imprint of a Papacy

Isabel Orellana

24 April, 2025

5 min

Cardinal Felipe Arizmendi: With the Risen Christ, There Is Hope

Felipe Arizmendi

24 April, 2025

6 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)