First Anniversary of Fratelli Tutti: Dream Together

Knowing Each Other as Brothers

Dr. Maria Elisabeth de los Rios Uriarte, Professor, and Researcher at the Faculty of Bioethics of the University of Anahuac of Mexico offers Exaudi’s readers her article on the first anniversary of Fratelli Tutti, Pope Francis’ Encyclical Letter on Fraternity and Social Friendship, signed on October 3, 2020.

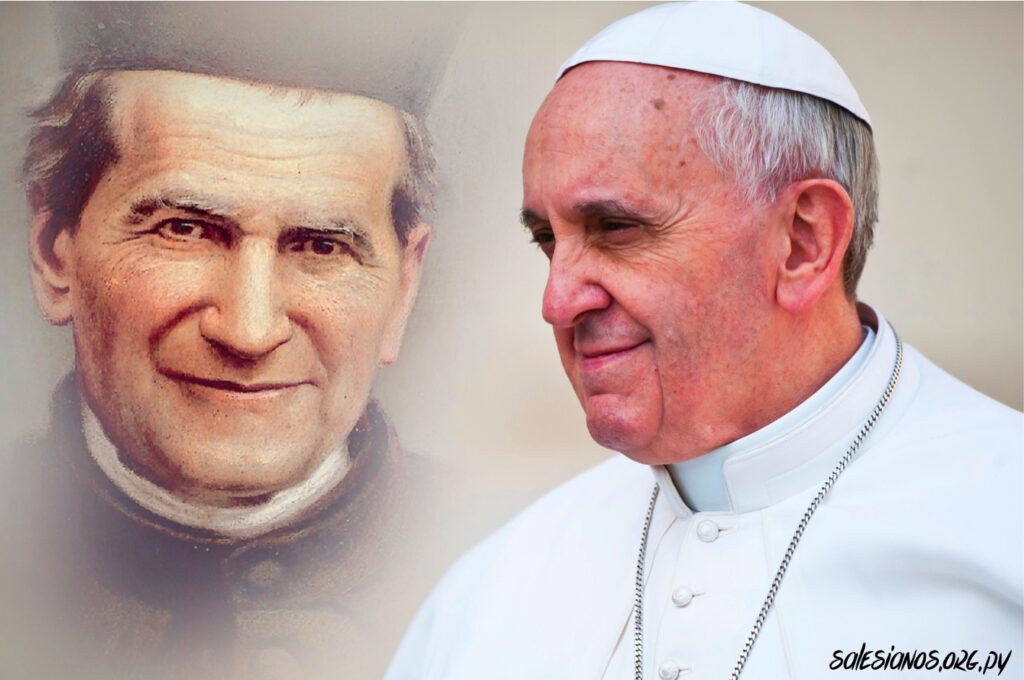

A year has gone by since Pope Francis signed the Encyclical Fratelli Tutti in Assisi. He did so at a time of difficult social, economic, and emotional consequences stemming from the global coronavirus health crisis.

Much has happened since then, ranging from the discovery of the vaccine against SARS-CoV2, which made a respite possible in many countries, and a hint of hope in the constant and not symmetric confrontations between Israel and Palestine, the explosion in Lebanon that cost so many lives, the wave of migrants in the coast of Ceuta in Spain and in Central America, the social explosions in Cuba, the arbitrary detentions in Nicaragua, the forced displacements in Chiapas, Mexico, and the coming to power of the Taliban government in Afghanistan, to mention but a few. Each one happened in different latitudes and separately. It would seem that but for the shared crisis of the coronavirus, we human beings don’t yield our individual space to share it with others; it would seem that a year on, we have done the opposite of what the mentioned Encyclical proposed.

To attend to the emergencies that arise in each region is important, but even more important is to build a common horizon, to dream together, and to have us all have a place in that dream.

It’s necessary to open our hearts today and not just tremble over our own tragedies but also the communal and global ones, and the only way to awaken this sensibility is to think and gestate an open and fraternal community among all and not “against all” (FT, 36). Each one of the crises mentioned is and must always be a crisis of all, not of a few.

The above is possible if the other is not seeing as a stranger but as a neighbor and that one also makes oneself a neighbor of the other (FT, 81). This pandemic made us strangers to one another and we learned to see one another at a distance, with suspicion and even discrimination if one was infected. In some way, it made us indifferent in face of the suffering of a sick brother.

In this recovery of life after the pandemic, it’s necessary to see the fallen on the side of the road, and to change our self-referential look for that which is able to welcome, to cure, to give one’s time, and to restore.

What has to happen for us to become neighbors of those that are strangers today?

The idea of progress proper of modernity has given us an inheritance of speed that cannot be reconciled with the culture of encounter. Progress is measured in results, it is measurable and quantifiable, in riches and accumulation of goods; for its part, the culture of encounter is measured in the depth of the heart, which is capable of feeling connected with the heart of many others beyond nationalities and borders.

To build these fraternal bonds means to come out of the logic of lineal progress and to place oneself in the logic of love because “the spiritual loftiness of human life is marked by love “ (FT, 92). In this logic, when we love, we are cast on a horizon of universal understanding, which is also existential (FT, 97).

Therefore, it’s this existential living of love that is translated into social friendship between nations, which saves us from remaining submerged in our own problems and indifferent to those of others. This social friendship is what urges aid among nations on the issue of vaccines, because there is still a very great gap between developed and developing countries on this subject, especially when we already know that only 1.1% of the population in these countries has been vaccinated.

Fraternal actions and shared solidarity do not increase riches and, even less so, are they profitable, but they do open the heart and enable one to think of a world that is less unequal, based on the value of the human person and not on his social usefulness. To invest in the poor will never be profitable but it will always be transforming. This has been taught to us by the social, philosophical, cultural, and theological movement of the so-called Economy of Francis, so present and also lived in the past year.

To have an open heart is not due to a monetary transaction or contract law but to gratuitousness. It is accepted for gratuity, not for utility.

These changes imply in people and States a gradual evolution from the inside to the outside, from me to the other. But, what animates this transit? Humanity seems to be clinging too much to itself and its goods and pleasures; hence, an additional ingredient is necessary that will stimulate selfless surrender, abandonment of one’s securities, and forgetfulness of what is one’s own. That something must be sought is what pairs us above our differences, whether natural or ideological; it’s something that goes beyond our shortcomings and our human stumbling; it’s something that moves, inspires, motivates, and stimulates.

The common bond that unites us is founded on the horizon of faith and on a faith that confirms what we are, all sons and daughters of the same Father, distinguished by solidarity and fraternity. Solidarity sinks its roots in the human will; fraternity does so in divine faith and hope.

To know ourselves brothers of each other gives us the security of sharing the same house and of being lovingly taken care of by the Father. It’s to trust that no one will stay behind if we all identify ourselves as brothers.

It’s possible to dream from there and to elaborate a common project (FT, 150). This project requires new men and women, capable of living in a different way, always going forth and in total and confident surrender. To dream the other’s dream and for the other to dream one’s dream is to dream the Father’s dream all of us together, as brothers.

We have already experienced fragility and inequality; we have already suffered and we have already been scourged by the local and global misfortune. Now, all we must do is to build, from the ruins of our egoism, a shared shelter.

Translation by Virginia M. Forrester

Related

Pope Francis’ Catechesis: The Rich Man. Jesus “Looked at Him with Love”

Exaudi Staff

09 April, 2025

4 min

Francis is recovering: progressing progressively

Exaudi Staff

08 April, 2025

2 min

The Pope to the Salesians: “Serve others without holding anything back”

Irene Vargas

07 April, 2025

2 min

The Pope: In convalescence, I feel the “finger of God” and experience his loving caress

Exaudi Staff

06 April, 2025

2 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)