Euthanasia or limitation of therapeutic effort in patients with ALS?

A complex ethical dilemma

A Peruvian woman with ALS asks for euthanasia in a country where it is illegal

The key point of ethical deliberation is to decide when any of these measures and care could be withdrawn. The difficulty is in objectively determining when they are causing an increase in suffering for the patient or prolonging a situation of suffering without allowing the arrival of natural death. That is when these measures are becoming a disthanasic action (therapeutic obstinacy).

María Benito, a Peruvian woman suffering from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) for ten years, has demanded that the State respect and protect her autonomy to decide on the end of her life.

It all started when the woman, who is now 65 years old and lives in Huancayo, began to experience the symptoms of ALS. After suffering progressive paralysis, she remains day and night in a bed in a nursing home in Lima, and for six years she has not been able to speak, so she communicates through her gaze thanks to an eye tracker that encodes what she wants to say with the help of a virtual keyboard.

Benito is losing her sight, which makes it increasingly difficult for her to communicate through this system, and her biggest fear is that she will not be able to communicate with the outside world. She now breathes with a cannula placed in her windpipe, and she needs tubes to urinate and feed.

This disease is incurable, chronic and degenerative and affects the nerve cells of the brain and spinal cord, causing loss of muscle control. This type of muscle paralysis, progressive and fatal, affects four out of every 100,000 inhabitants.

In April 2023, Benito requested the Social Health Insurance (EsSalud), former Peruvian Institute of Social Security – IPSS, to remove the mechanical ventilator, to which she remains connected, in order to cause her death. According to her lawyer, Josefina Miró, this request is based on articles 4 and 15 of the General Health Law. “Due to the progressive progression of her illness, she is suffering in life. For this reason, she claimed to be able to exercise her right to a dignified death,” the lawyer stated.

Benito’s lawyer assures that EsSalud initially denied the request, alleging that “medical professionals are prohibited from acting directly to cause the patient’s death, so they will not remove mechanical ventilation. Furthermore, since there is no legislation on euthanasia, it is up to the judicial authorities to determine the origin of the patient’s request.”

Since euthanasia is a crime in Peru, María’s family at some point studied the possibility of traveling to Switzerland and Colombia where it is legal to do so, but ultimately the idea did not prosper.

An unprecedented failure

However, on February 1, the Third Constitutional Chamber of the Superior Court of Lima issued an unprecedented ruling for ALS patients in favor of María, recognizing her right not to receive medical treatments that would keep her alive in an artificial form. However, despite there already being a ruling on this case, Essalud has not yet executed the provisions of the Judiciary.

First euthanasia in Peru

However, despite the illegality of euthanasia in Peru, there is data that another woman who suffered from polymyositis since she was 12 years old, Ana Estrada, requested in February 2023 to end her life. In January 2024, the procedure was accepted, and on April 21, she died. In this way, Estrada has become the first case in Peru of a person dying after the application of euthanasia.

Bioethical assessment

Life support measures and care such as nutrition, hydration, mechanical ventilation or hygiene, in palliative patients, do not constitute acts of therapeutic obstinacy and, therefore, must be provided. There are exceptions to this rule, such as the case of terminally ill patients with pulmonary edema in whom hydration can aggravate dyspnea or patients in brain death where maintaining assisted breathing does not make sense.

The key point of ethical deliberation is to decide when any of these measures and care could be withdrawn. The difficulty is in objectively determining when they are causing an increase in suffering for the patient or prolonging a situation of suffering without allowing the arrival of natural death. That is, when these measures are becoming a disthanasic action (therapeutic obstinacy).

In the case of patients with ALS, mechanical ventilation is a support measure freely chosen by the patient at a time during their illness and which allows them to maintain their life.

The patient’s expressed desire to die does not in itself justify the withdrawal of life support. In this case, the attitude could be considered euthanasia.

However, if it were a consequence of a condition that aggravated over time, and the negative evolution of your clinical situation, with suffering that becomes unbearable and without – as is the case – any hope of improvement, your treatment should be attended to. request for withdrawal of mechanical ventilation.

This request should only be accepted if it responds to a conscious, considered and duly informed decision.

This decision should never be considered without first having made available all the technical and human resources to reduce their suffering through comprehensive care by palliative care teams.

The withdrawal of mechanical ventilation would also not be acceptable if the request were the result of a psychopathological process, such as depression, that could be treated.

New possibilities for ALS patients

A recent news story exposes the case of an ALS patient who underwent a brain implant that allowed him to communicate again when he had already lost this ability. This medical advance will allow many patients to maintain an acceptable level of communication with their environment, which can help facilitate their care and meet their needs.

Julio Tudela – Germán Cerdá – Cristina Castillo – Bioethics Observatory – Life Sciences Institute – Catholic University of Valencia

Related

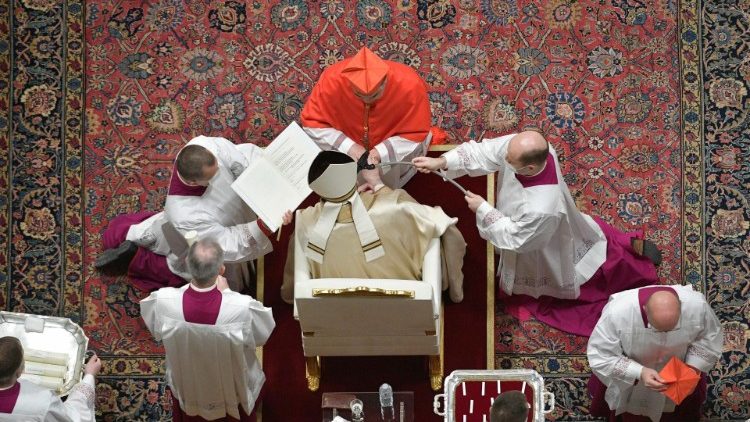

The heart of the Church beats between mourning and hope

Exaudi Staff

24 April, 2025

2 min

What is a Conclave? The Process That Elects the New Pope

Exaudi Staff

24 April, 2025

7 min

Current Status of the College of Cardinals

Exaudi Staff

23 April, 2025

14 min

The Challenges of the Next Pope and the Path of Grace

Javier Ferrer García

23 April, 2025

4 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)