Emilio Girón: Stubbornness and Tinto de Verano

The story of an ordinary man whose loyalty and perseverance transformed the ordinary into the extraordinary

With the arrival of spring, Emilio Girón Huélamo passed away at the age of 101. He was a member of Opus Dei and lived in Madrid. Not many people knew him; he never held leadership positions in the Work, and he didn’t appear in documentaries or on lists of the most influential or powerful.

He came from an ordinary family; his father worked as a stagehand at the Lara Theater. He spent the Spanish Civil War safely in a small town and returned to Madrid to study business. Likewise, he wanted to meet the author of Camino and went with some friends. He joined Opus Dei in 1946, shortly before his 23rd birthday. From then on, he lived an ordinary life that attracted no one in particular, beyond his family, friends, coworkers, and the various members of the Work with whom he shared his faith, projects, endeavors, dreams, sorrows, and joys.

Like any Spaniard of his time, he had to earn a living and did everything from selling chicken feed to marketing various products, working in a bank branch in a town in Toledo, selling books, and decorating houses and hotels. He went to Chile in the mid-1950s to help with the beginnings of the Work there and earned a living as a bookseller. A few years later, he returned because his family asked him to care for some young nieces due to their mother’s serious illness. When his nieces finished their studies and married, Emilio returned to live in a Work center. For other periods, he lived Monday through Friday in a rented apartment outside of Madrid for work reasons. From here to there, with good humor and initiative.

He had many obvious defects that he struggled with throughout his life, and which he used to turn into virtue, to refine his character, to serve others, and to ask for forgiveness. The most notable was his stubbornness, which he transformed into perseverance in pursuing so many personal, family, work, and health matters, thanks to which he was “revived” on several occasions and endured beyond a hundred years. He also helped to be constant and remain faithful to his vocation without lukewarmness, as the founder of the Work in the Forge said (489): Clear proof of lukewarmness is the lack of supernatural “stubbornness,” the strength to persevere in work, to not stop until the “last stone” is laid.

He had many obvious defects that he struggled with throughout his life, and which he used to turn into virtue, to refine his character, to serve others, and to ask for forgiveness. The most notable was his stubbornness, which he transformed into perseverance in pursuing so many personal, family, work, and health matters, thanks to which he was “revived” on several occasions and endured beyond a hundred years. He also helped to be constant and remain faithful to his vocation without lukewarmness, as the founder of the Work in the Forge said (489): Clear proof of lukewarmness is the lack of supernatural “stubbornness,” the strength to persevere in work, to not stop until the “last stone” is laid.

Another flaw was his excessive desire for independence and his own judgment, perhaps taking literally what he heard Saint Josemaría say in his homily at the University of Navarra: “Interpret my words, then, as what they are: a call to exercise—daily, not only in emergency situations—your rights; and to nobly fulfill your obligations as citizens—in political life, in economic life, in university life, in professional life—courageously assuming all the consequences of your free decisions, bearing the personal independence that is yours.” Although in the last years of his life, he had to submit to the absolute physical dependence of the members of the Work who lived with him, his nieces, and professional caregivers to make ends meet. Neither his family nor the Work lacked affection and attention to look after this ordinary man whom they loved. He cared and was cared for.

Such an ordinary life was filled with anecdotes that the peculiarity of his temperament multiplied. For example, he slept with the window open every day of the year. Three incidents can illustrate some of his life’s interests. On one occasion, as we got up from the sofas after a family gathering, I arranged and fluffed some cushions. Emilio smiled and told me, “I learned that from Saint Josemaría in the 1940s.” He said this with shining eyes, showing his joy at seeing other younger people trying to live the spirit of Opus Dei in the small things of ordinary life. He learned that spirit from others and passed it on whenever he could.

Likewise, he was interested in helping the people he loved and interacted with get to know God. One day, already 96 years old, he said to me, “Carlos, you have to set up Twitter for me and teach me how to use it.” I inquired about the reason, as the task didn’t seem easy, and he explained it to me: “I heard that young people are now communicating through that network, and I want to send a message to my great-niece so she can prepare well for her Confirmation.” I suggested I could call him, but he replied that that would be very complicated.

At 99 years old, he contracted Covid and had to be admitted. There, in the hospital room, he asked quite naturally: “Can I have a tinto de verano here?” He had a great capacity for enjoyment, knowing what he liked and wanted, thanking God for that pleasure, and sharing it.

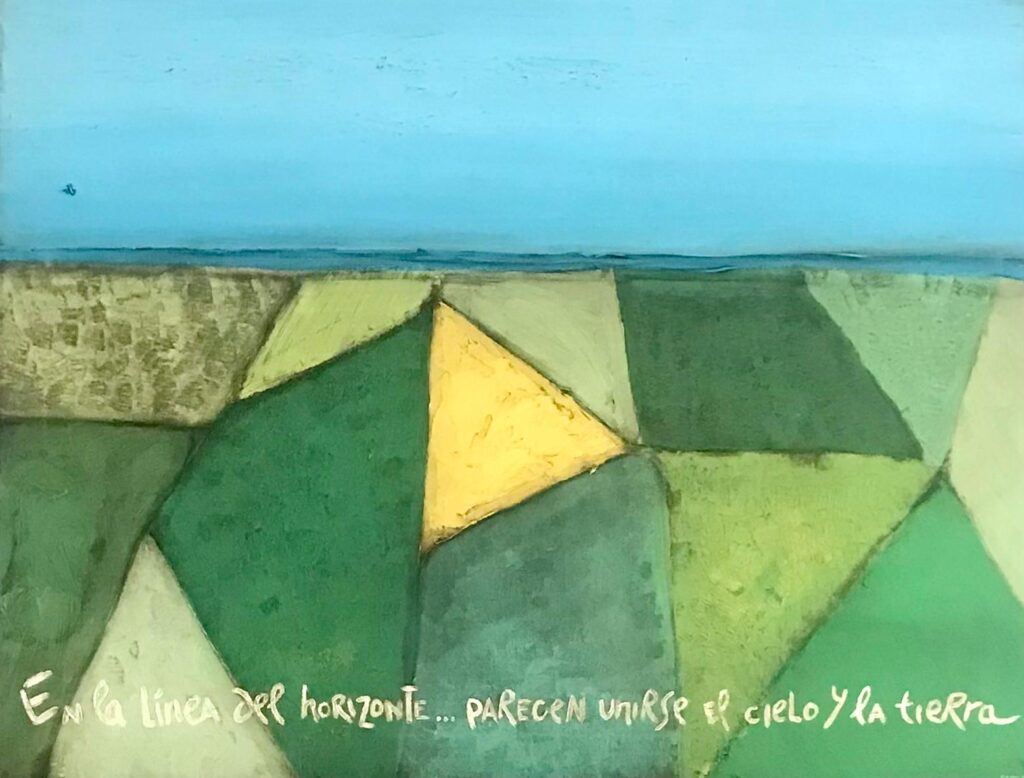

A normal man who trusted in God, prayed every day, attended the sacraments, and strove to put his life at the service of others. He lived an ordinary life that won’t appear in any history book, but which his guardian angel did record in the book of his life. He had heard it from the lips of Saint Josemaría and experienced it so many times: “On the horizon, my children, heaven and earth seem to unite. But no, where they truly come together is in your hearts, when you live an ordinary life in holiness.”

Related

Discover Your Vocation: The Divine Path to a Full and Holy Life

Patricia Jiménez Ramírez

01 April, 2025

5 min

“I Stay With Those Who Care For Me”: An Anthem to Luminous People

José Miguel Ponce

01 April, 2025

2 min

The Keys to Being a Good Priest

Javier Ferrer García

01 April, 2025

4 min

Francis’s 38 Days in the Hospital: Appointments and Cries for Peace

Exaudi Staff

01 April, 2025

5 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)