Edith Stein: the relevance of a woman, a thought and an experience

Interview with Rodrigo Guerra

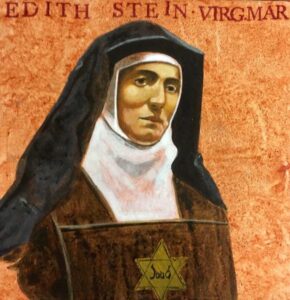

On August 9, 1942, Saint Benedicta of the Cross was executed in the Auschwitz concentration camp. Her life, her thought, and her spirituality have become an obligatory reference for those who wish to understand the meaning and vocation of women in the contemporary world.

We interviewed Rodrigo Guerra, secretary of the Pontifical Commission for Latin America and founder of the Center for Advanced Social Research (CISAV), about the importance of the testimony of this converted Jewess, Discalced Carmelite, philosopher and mystic.

EXAUDI: How did you learn about the life and thought of Edith Stein?

RG: In 1989, Brother Abelardo Lobato O.P. attended, to my surprise, a conference I gave at the Third World Congress of Christian Philosophy in Quito, Ecuador. In those years, I had just begun my research into the way of studying the person and his or her constitutive relationality using a phenomenologically reformulated metaphysics. When I finished my presentation, he approached me and told me, among other things, that I should study Edith Stein. He had written a wonderful book entitled: “The Question About Woman” (Sígueme, Salamanca, 1976) in which he presented the life, thought and philosophy of women of Simone de Beauvoir, Simone Weil and Edith Stein. I read it, and it had a strong impact on me. Then I studied the biography written by Teresia Renata Posselt OCD and began to gather everything that had been published in Spanish at that time about the saint. This was the beginning of an encounter that has not yet ended and that always fills me with joy and enthusiasm.

EXAUDI: How can a person begin to study Edith Stein?

RG: It was very useful for me to learn about her life. Knowing her personal history, one can better understand what concerned her. I have met some people who study this or that text of Stein’s without this biographical approach, and suddenly, they fail to grasp that all thought is existentially motivated, that is, they fail to grasp that her high metaphysical reflection does not seek to be anything other than a meditation on the meaning of real life, and not a mere conceptual game.

EXAUDI: What biographies would you recommend to us besides the one you mentioned at the beginning?

RG: There is a small but very good biography written by Waltraud Hersbrith, entitled: “The true face of Edith Stein” (Encuentro, Madrid, 1992). It has a particular merit: it was written by a Carmelite who has mastery of phenomenology and Carmelite spirituality. There is another, written by Francesco Salvarani: “Edith Stein: daughter of Israel and of the Church” (Palabra, Madrid, 2012), which follows closely the many letters that Edith wrote to her friends. And of course, there is the one by Francisco Javier Sancho: “Edith Stein, model and teacher of spirituality” (Monte Carmelo, Burgos, 1998). In all of them, it is well explained how the martyrdom of Edith Stein is a prophetic sign that helps us to clarify today’s History.

EXAUDI: What does Edith Stein’s philosophy contribute to the understanding of female identity?

RG: One of the most fascinating themes in Edith Stein’s work is her reflection on women. She says: “we are obliged to consider the problem of our own reality and our own life. We cannot ignore the problem of what we are and what we should be.” Man and woman realize humanity in their own way, as if with a different modulation. For Edith Stein, it is the soul that shapes the body with its individual sexual determination. In doing so, she criticizes the theories that claim that sexuality is primarily based on corporeality. The female person has an inner configuration that is expressed on the outside and that is complementary to the male. It is this inner, spiritual-emotional reality that directs the woman towards the man and the man towards the woman. In other words, it is not mere biological instinct that relates women to men, and vice versa. We are both called to order each other, not to live in a power struggle, but in true community life, which is always more than an agglomeration of bodies. Femininity must be educated to blossom properly. Edith Stein is aware that there are alienated and alienating forms of being feminine. For example, in professional life, women must remain women and not fall tacitly or explicitly into the easy trap of becoming masculine, of becoming violent or vulgar, in order to try to claim their position in social life. Women must be “Wahrheitsucher”, a seeker of truth, of their own truth, above all else.

EXAUDI: What relevance can Edith Stein have in Latin America and Spain?

EXAUDI: What relevance can Edith Stein have in Latin America and Spain?

RG: Edith Stein may seem like an interesting but distant case for the life of society and the Church in Latin America and Spain. However, I am one of those who think that one day the Church will have to recognize her as a “Doctor of the Church,” since her teaching has a universal dimension that we need to discover today. Let me explain: in times when universal truths seem to be sacrificed in the name of merely contextual truths, Stein offers a re-argumentation of the meta-contextual (meta-physical) scope of human intelligence; in times of intense debates on sexual identity and gender identity, Stein offers non-complacent solutions that open new horizons for both conservatives and liberals; in times when it is necessary to delve into a solid, metaphysically founded, and not merely superficial, feminism, Stein points out a path that must be followed in the matter of the radical foundation of sexual differentiation. I sincerely believe that meeting Edith Stein is good for all of us. Her anti-conformist, anti-bourgeois, anti-immanentist thought is critical and liberating. And, at the same time, it is rigorous, multidimensional, and strongly resistant to easy simplifications.

EXAUDI: What would you say to a woman who wants to get closer to Edith Stein and not lose heart when faced with her many philosophical and spiritual works?

RG: I think that what motivates us most to undertake an adventure like studying Edith Stein’s legacy is to understand that the path to truth is always an experience. In other words: getting closer to Stein is giving oneself the opportunity to verify in one’s own life the truth that she carries in her statements. The truth, so mistreated today, reappears when you and I open ourselves to the totality of experience and learn to embrace it faithfully, without imposing our prejudices on it. It is the truth that makes us free and generates within us a passion that leads to an expansion of our own humanity. Edith Stein, reflecting on her life, wrote: “I could not act without an inner impulse. The decisions I made always came from a depth that I myself did not know. Once something rose to the clear light of conscience and took rational form, nothing could stop me. Certainly, I experienced a kind of sporting pleasure in undertaking the seemingly impossible.”

EXAUDI: What does Edith Stein mean to Pope Francis?

RG: Pope Francis, no less, has entrusted Edith Stein with peace in Ukraine on August 9, 2023. Moreover, the Holy Father has said since August 7, 2019: “I invite everyone to look at her courageous choices, expressed in an authentic conversion to Christ, as well as in the dedication of her life against every form of intolerance and ideological perversion.” These are strong words that invite us to discover in her a healthy medicine against the easy ideological colonizations that flow today in so many crucial issues for the culture of our time.

EXAUDI: How has the encounter with Edith Stein helped Rodrigo Guerra?

RG: Edith Stein was a woman of friends who also sought the truth: “extra communio personarum nulla philosophia”, outside the company of friends, it is not possible to do authentic philosophy. Close friends who marked her life were: Adolf Reinach, Hedwig Conrad-Martius, Roman Ingarden and the master Husserl, among others. In the same way, I cannot ignore the friends who have helped me understand Edith Stein’s path, and with it, to love the truth a little more: Josef Seifert, John Crosby, John White, Rocco Buttiglione, and very particularly, Eduardo González di Piero and Mariano Crespo. These last two are, in my view, highly qualified exponents of the proper interpretation of Edith Stein’s originality in the context of contemporary phenomenological philosophy. Both have deepened and clarified things about Stein that for years were not well understood and attended to.

On the other hand, Edith Stein was a woman of enormous interior life. Carmelite spirituality offered her an explanation of what God himself was slowly working within her, even before she herself converted to the Christian faith. This, in my case, has also given me much light. God, who is the Truth, intuits us and anticipates us, from our most modest babblings and explorations. God intercepts us and surprises us, even in the midst of the fall, showing us that the Truth entails the Cross, but that the Cross is the path of redemption for our fragile, wounded humanity. The “science of the cross,” of which Edith Stein spoke, is not a dark alley. It is a window that leads us, through a peculiar purification, to the greatest freedom and the deepest joy.

Related

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)