Dilexit Nos

On the human and divine love of the heart of Jesus Christ

ENCICLICAL LETTER

DILEXIT NOS

OF THE HOLY FATHER

FRANCIS

ON THE HUMAN AND DIVINE LOVE

OF THE HEART OF JESUS CHRIST

1. “HE LOVED US”, Saint Paul says of Christ (cf. Rom 8:37), in order to make us realize that nothing can ever “separate us” from that love (Rom 8:39). Paul could say this with certainty because Jesus himself had told his disciples, “I have loved you” (Jn 15:9, 12). Even now, the Lord says to us, “I have called you friends” (Jn 15:15). His open heart has gone before us and waits for us, unconditionally, asking only to offer us his love and friendship. For “he loved us first” (cf. 1 Jn 4:10). Because of Jesus, “we have come to know and believe in the love that God has for us” (1 Jn 4:16).

CHAPTER ONE

THE IMPORTANCE OF THE HEART

2. The symbol of the heart has often been used to express the love of Jesus Christ. Some have questioned whether this symbol is still meaningful today. Yet living as we do in an age of superficiality, rushing frenetically from one thing to another without really knowing why, and ending up as insatiable consumers and slaves to the mechanisms of a market unconcerned about the deeper meaning of our lives, all of us need to rediscover the importance of the heart. [1]

WHAT DO WE MEAN BY “THE HEART”?

3. In classical Greek, the word kardía denotes the inmost part of human beings, animals and plants. For Homer, it indicates not only the centre of the body, but also the human soul and spirit. In the Iliad, thoughts and feelings proceed from the heart and are closely bound one to another. [2] The heart appears as the locus of desire and the place where important decisions take shape. [3] In Plato, the heart serves, as it were, to unite the rational and instinctive aspects of the person, since the impulses of both the higher faculties and the passions were thought to pass through the veins that converge in the heart. [4] From ancient times, then, there has been an appreciation of the fact that human beings are not simply a sum of different skills, but a unity of body and soul with a coordinating centre that provides a backdrop of meaning and direction to all that a person experiences.

4. The Bible tells us that, “the Word of God is living and active… it is able to judge the thoughts and intentions of the heart” (Heb 4:12). In this way, it speaks to us of the heart as a core that lies hidden beneath all outward appearances, even beneath the superficial thoughts that can lead us astray. The disciples of Emmaus, on their mysterious journey in the company of the risen Christ, experienced a moment of anguish, confusion, despair and disappointment. Yet, beyond and in spite of this, something was happening deep within them: “Were not our hearts burning within us while he was talking to us on the road?” (Lk 24:32).

5. The heart is also the locus of sincerity, where deceit and disguise have no place. It usually indicates our true intentions, what we really think, believe and desire, the “secrets” that we tell no one: in a word, the naked truth about ourselves. It is the part of us that is neither appearance or illusion, but is instead authentic, real, entirely “who we are”. That is why Samson, who kept from Delilah the secret of his strength, was asked by her, “How can you say, ‘I love you’, when your heart is not with me?” (Judg 16:15). Only when Samson opened his heart to her, did she realize “that he had told her his whole secret” (Judg 16:18).

6. This interior reality of each person is frequently concealed behind a great deal of “foliage”, which makes it difficult for us not only to understand ourselves, but even more to know others: “The heart is devious above all else; it is perverse, who can understand it?” (Jer 17:9). We can understand, then, the advice of the Book of Proverbs: “Keep your heart with all vigilance, for from it flow the springs of life; put away from you crooked speech” (4:23-24). Mere appearances, dishonesty and deception harm and pervert the heart. Despite our every attempt to appear as something we are not, our heart is the ultimate judge, not of what we show or hide from others, but of who we truly are. It is the basis for any sound life project; nothing worthwhile can be undertaken apart from the heart. False appearances and untruths ultimately leave us empty-handed.

7. As an illustration of this, I would repeat a story I have already told on another occasion. “For the carnival, when we were children, my grandmother would make a pastry using a very thin batter. When she dropped the strips of batter into the oil, they would expand, but then, when we bit into them, they were empty inside. In the dialect we spoke, those cookies were called ‘lies’… My grandmother explained why: ‘Like lies, they look big, but are empty inside; they are false, unreal’”. [5]

8. Instead of running after superficial satisfactions and playing a role for the benefit of others, we would do better to think about the really important questions in life. Who am I, really? What am I looking for? What direction do I want to give to my life, my decisions and my actions? Why and for what purpose am I in this world? How do I want to look back on my life once it ends? What meaning do I want to give to all my experiences? Who do I want to be for others? Who am I for God? All these questions lead us back to the heart.

RETURNING TO THE HEART

9. In this “liquid” world of ours, we need to start speaking once more about the heart and thinking about this place where every person, of every class and condition, creates a synthesis, where they encounter the radical source of their strengths, convictions, passions and decisions. Yet, we find ourselves immersed in societies of serial consumers who live from day to day, dominated by the hectic pace and bombarded by technology, lacking in the patience needed to engage in the processes that an interior life by its very nature requires. In contemporary society, people “risk losing their centre, the centre of their very selves”. [6] “Indeed, the men and women of our time often find themselves confused and torn apart, almost bereft of an inner principle that can create unity and harmony in their lives and actions. Models of behaviour that, sadly, are now widespread exaggerate our rational-technological dimension or, on the contrary, that of our instincts”. [7] No room is left for the heart.

10. The issues raised by today’s liquid society are much discussed, but this depreciation of the deep core of our humanity – the heart – has a much longer history. We find it already present in Hellenic and pre-Christian rationalism, in post-Christian idealism and in materialism in its various guises. The heart has been ignored in anthropology, and the great philosophical tradition finds it a foreign notion, preferring other concepts such as reason, will or freedom. The very meaning of the term is imprecise and hard to situate within our human experience. Perhaps this is due to the difficulty of treating it as a “clear and distinct idea”, or because it entails the question of self-understanding, where the deepest part of us is also that which is least known. Even encountering others does not necessarily prove to be a way of encountering ourselves, inasmuch as our thought patterns are dominated by an unhealthy individualism. Many people feel safer constructing their systems of thought in the more readily controllable domain of intelligence and will. The failure to make room for the heart, as distinct from our human powers and passions viewed in isolation from one another, has resulted in a stunting of the idea of a personal centre, in which love, in the end, is the one reality that can unify all the others.

11. If we devalue the heart, we also devalue what it means to speak from the heart, to act with the heart, to cultivate and heal the heart. If we fail to appreciate the specificity of the heart, we miss the messages that the mind alone cannot communicate; we miss out on the richness of our encounters with others; we miss out on poetry. We also lose track of history and our own past, since our real personal history is built with the heart. At the end of our lives, that alone will matter.

12. It must be said, then, that we have a heart, a heart that coexists with other hearts that help to make it a “Thou”. Since we cannot develop this theme at length, we will take a character from one of Dostoevsky’s novels, Nikolai Stavrogin. [8] Romano Guardini argues that Stavrogin is the very embodiment of evil, because his chief trait is his heartlessness: “Stavrogin has no heart, hence his mind is cold and empty and his body sunken in bestial sloth and sensuality. He has no heart, hence he can draw close to no one and no one can ever truly draw close to him. For only the heart creates intimacy, true closeness between two persons. Only the heart is able to welcome and offer hospitality. Intimacy is the proper activity and the domain of the heart. Stavrogin is always infinitely distant, even from himself, because a man can enter into himself only with the heart, not with the mind. It is not in a man’s power to enter into his own interiority with the mind. Hence, if the heart is not alive, man remains a stranger to himself”. [9]

13. All our actions need to be put under the “political rule” of the heart. In this way, our aggressiveness and obsessive desires will find rest in the greater good that the heart proposes and in the power of the heart to resist evil. The mind and the will are put at the service of the greater good by sensing and savouring truths, rather than seeking to master them as the sciences tend to do. The will desires the greater good that the heart recognizes, while the imagination and emotions are themselves guided by the beating of the heart.

14. It could be said, then, that I am my heart, for my heart is what sets me apart, shapes my spiritual identity and puts me in communion with other people. The algorithms operating in the digital world show that our thoughts and will are much more “uniform” than we had previously thought. They are easily predictable and thus capable of being manipulated. That is not the case with the heart.

15. The word “heart” proves its value for philosophy and theology in their efforts to reach an integral synthesis. Nor can its meaning be exhausted by biology, psychology, anthropology or any other science. It is one of those primordial words that “describe realities belonging to man precisely in so far as he is one whole (as a corporeo-spiritual person)”. [10] It follows that biologists are not being more “realistic” when they discuss the heart, since they see only one aspect of it; the whole is not less real, but even more real. Nor can abstract language ever acquire the same concrete and integrative meaning. The word “heart” evokes the inmost core of our person, and thus it enables us to understand ourselves in our integrity and not merely under one isolated aspect.

16. This unique power of the heart also helps us to understand why, when we grasp a reality with our heart, we know it better and more fully. This inevitably leads us to the love of which the heart is capable, for “the inmost core of reality is love”. [11] For Heidegger, as interpreted by one contemporary thinker, philosophy does not begin with a simple concept or certainty, but with a shock: “Thought must be provoked before it begins to work with concepts or while it works with them. Without deep emotion, thought cannot begin. The first mental image would thus be goose bumps. What first stirs one to think and question is deep emotion. Philosophy always takes place in a basic mood ( Stimmung)”. [12] That is where the heart comes in, since it “houses the states of mind and functions as a ‘keeper of the state of mind’. The ‘heart’ listens in a non-metaphoric way to ‘the silent voice’ of being, allowing itself to be tempered and determined by it”. [13]

THE HEART UNITES THE FRAGMENTS

17. At the same time, the heart makes all authentic bonding possible, since a relationship not shaped by the heart is incapable of overcoming the fragmentation caused by individualism. Two monads may approach one another, but they will never truly connect. A society dominated by narcissism and self-centredness will increasingly become “heartless”. This will lead in turn to the “loss of desire”, since as other persons disappear from the horizon we find ourselves trapped within walls of our own making, no longer capable of healthy relationships. [14] As a result, we also become incapable of openness to God. As Heidegger puts it, to be open to the divine we need to build a “guest house”. [15]

18. We see, then, that in the heart of each person there is a mysterious connection between self-knowledge and openness to others, between the encounter with one’s personal uniqueness and the willingness to give oneself to others. We become ourselves only to the extent that we acquire the ability to acknowledge others, while only those who can acknowledge and accept themselves are then able to encounter others.

19. The heart is also capable of unifying and harmonizing our personal history, which may seem hopelessly fragmented, yet is the place where everything can make sense. The Gospel tells us this in speaking of Our Lady, who saw things with the heart. She was able to dialogue with the things she experienced by pondering them in her heart, treasuring their memory and viewing them in a greater perspective. The best expression of how the heart thinks is found in the two passages in Saint Luke’s Gospel that speak to us of how Mary “treasured (synetérei) all these things and pondered (symbállousa) them in her heart” (cf. Lk 2:19 and 51). The Greek verb symbállein, “ponder”, evokes the image of putting two things together (“symbols”) in one’s mind and reflecting on them, in a dialogue with oneself. In Luke 2:51, the verb used is dietérei, which has the sense of “keep”. What Mary “kept” was not only her memory of what she had seen and heard, but also those aspects of it that she did not yet understand; these nonetheless remained present and alive in her memory, waiting to be “put together” in her heart.

20. In this age of artificial intelligence, we cannot forget that poetry and love are necessary to save our humanity. No algorithm will ever be able to capture, for example, the nostalgia that all of us feel, whatever our age, and wherever we live, when we recall how we first used a fork to seal the edges of the pies that we helped our mothers or grandmothers to make at home. It was a moment of culinary apprenticeship, somewhere between child-play and adulthood, when we first felt responsible for working and helping one another. Along with the fork, I could also mention thousands of other little things that are a precious part of everyone’s life: a smile we elicited by telling a joke, a picture we sketched in the light of a window, the first game of soccer we played with a rag ball, the worms we collected in a shoebox, a flower we pressed in the pages of a book, our concern for a fledgling bird fallen from its nest, a wish we made in plucking a daisy. All these little things, ordinary in themselves yet extraordinary for us, can never be captured by algorithms. The fork, the joke, the window, the ball, the shoebox, the book, the bird, the flower: all of these live on as precious memories “kept” deep in our heart.

21. This profound core, present in every man and woman, is not that of the soul, but of the entire person in his or her unique psychosomatic identity. Everything finds its unity in the heart, which can be the dwelling-place of love in all its spiritual, psychic and even physical dimensions. In a word, if love reigns in our heart, we become, in a complete and luminous way, the persons we are meant to be, for every human being is created above all else for love. In the deepest fibre of our being, we were made to love and to be loved.

22. For this reason, when we witness the outbreak of new wars, with the complicity, tolerance or indifference of other countries, or petty power struggles over partisan interests, we may be tempted to conclude that our world is losing its heart. We need only to see and listen to the elderly women – from both sides – who are at the mercy of these devastating conflicts. It is heart-breaking to see them mourning for their murdered grandchildren, or longing to die themselves after losing the homes where they spent their entire lives. Those women, who were often pillars of strength and resilience amid life’s difficulties and hardships, now, at the end of their days, are experiencing, in place of a well-earned rest, only anguish, fear and outrage. Casting the blame on others does not resolve these shameful and tragic situations. To see these elderly women weep, and not feel that this is something intolerable, is a sign of a world that has grown heartless.

23. Whenever a person thinks, questions and reflects on his or her true identity, strives to understand the deeper questions of life and to seek God, or experiences the thrill of catching a glimpse of truth, it leads to the realization that our fulfilment as human beings is found in love. In loving, we sense that we come to know the purpose and goal of our existence in this world. Everything comes together in a state of coherence and harmony. It follows that, in contemplating the meaning of our lives, perhaps the most decisive question we can ask is, “Do I have a heart?”

FIRE

24. All that we have said has implications for the spiritual life. For example, the theology underlying the Spiritual Exercises of Saint Ignatius Loyola is based on “affection” ( affectus). The structure of the Exercises assumes a firm and heartfelt desire to “rearrange” one’s life, a desire that in turn provides the strength and the wherewithal to achieve that goal. The rules and the compositions of place that Ignatius furnishes are in the service of something much more important, namely, the mystery of the human heart. Michel de Certeau shows how the “movements” of which Ignatius speaks are the “inbreaking” of God’s desire and the desire of our own heart amid the orderly progression of the meditations. Something unexpected and hitherto unknown starts to speak in our heart, breaking through our superficial knowledge and calling it into question. This is the start of a new process of “setting our life in order”, beginning with the heart. It is not about intellectual concepts that need to be put into practice in our daily lives, as if affectivity and practice were merely the effects of – and dependent upon – the data of knowledge. [16]

25. Where the thinking of the philosopher halts, there the heart of the believer presses on in love and adoration, in pleading for forgiveness and in willingness to serve in whatever place the Lord allows us to choose, in order to follow in his footsteps. At that point, we realize that in God’s eyes we are a “Thou”, and for that very reason we can be an “I”. Indeed, only the Lord offers to treat each one of us as a “Thou”, always and forever. Accepting his friendship is a matter of the heart; it is what constitutes us as persons in the fullest sense of that word.

26. Saint Bonaventure tells us that in the end we should not pray for light, but for “raging fire”. [17] He teaches that, “faith is in the intellect, in such a way as to provoke affection. In this sense, for example, the knowledge that Christ died for us does not remain knowledge, but necessarily becomes affection, love”. [18] Along the same lines, Saint John Henry Newman took as his motto the phrase Cor ad cor loquitur, since, beyond all our thoughts and ideas, the Lord saves us by speaking to our hearts from his Sacred Heart. This realization led him, the distinguished intellectual, to recognize that his deepest encounter with himself and with the Lord came not from his reading or reflection, but from his prayerful dialogue, heart to heart, with Christ, alive and present. It was in the Eucharist that Newman encountered the living heart of Jesus, capable of setting us free, giving meaning to each moment of our lives, and bestowing true peace: “O most Sacred, most loving Heart of Jesus, Thou art concealed in the Holy Eucharist, and Thou beatest for us still… I worship Thee then with all my best love and awe, with my fervent affection, with my most subdued, most resolved will. O my God, when Thou dost condescend to suffer me to receive Thee, to eat and drink Thee, and Thou for a while takest up Thy abode within me, O make my heart beat with Thy Heart. Purify it of all that is earthly, all that is proud and sensual, all that is hard and cruel, of all perversity, of all disorder, of all deadness. So fill it with Thee, that neither the events of the day nor the circumstances of the time may have power to ruffle it, but that in Thy love and Thy fear it may have peace”. [19]

27. Before the heart of Jesus, living and present, our mind, enlightened by the Spirit, grows in the understanding of his words and our will is moved to put them into practice. This could easily remain on the level of a kind of self-reliant moralism. Hearing and tasting the Lord, and paying him due honour, however, is a matter of the heart. Only the heart is capable of setting our other powers and passions, and our entire person, in a stance of reverence and loving obedience before the Lord.

THE WORLD CAN CHANGE, BEGINNING WITH THE HEART

28. It is only by starting from the heart that our communities will succeed in uniting and reconciling differing minds and wills, so that the Spirit can guide us in unity as brothers and sisters. Reconciliation and peace are also born of the heart. The heart of Christ is “ecstasy”, openness, gift and encounter. In that heart, we learn to relate to one another in wholesome and happy ways, and to build up in this world God’s kingdom of love and justice. Our hearts, united with the heart of Christ, are capable of working this social miracle.

29. Taking the heart seriously, then, has consequences for society as a whole. The Second Vatican Council teaches that, “every one of us needs a change of heart; we must set our gaze on the whole world and look to those tasks we can all perform together in order to bring about the betterment of our race”. [20] For “the imbalances affecting the world today are in fact a symptom of a deeper imbalance rooted in the human heart”. [21] In pondering the tragedies afflicting our world, the Council urges us to return to the heart. It explains that human beings “by their interior life, transcend the entire material universe; they experience this deep interiority when they enter into their own heart, where God, who probes the heart, awaits them, and where they decide their own destiny in the sight of God”. [22]

30. This in no way implies an undue reliance on our own abilities. Let us never forget that our hearts are not self-sufficient, but frail and wounded. They possess an ontological dignity, yet at the same time must seek an ever more dignified life. [23] The Second Vatican Council points out that “the ferment of the Gospel has aroused and continues to arouse in human hearts an unquenchable thirst for human dignity”. [24] Yet to live in accordance with this dignity, it is not enough to know the Gospel or to carry out mechanically its demands. We need the help of God’s love. Let us turn, then, to the heart of Christ, that core of his being, which is a blazing furnace of divine and human love and the most sublime fulfilment to which humanity can aspire. There, in that heart, we truly come at last to know ourselves and we learn how to love.

31. In the end, that Sacred Heart is the unifying principle of all reality, since “Christ is the heart of the world, and the paschal mystery of his death and resurrection is the centre of history, which, because of him, is a history of salvation”. [25] All creatures “are moving forward with us and through us towards a common point of arrival, which is God, in that transcendent fullness where the risen Christ embraces and illumines all things”. [26] In the presence of the heart of Christ, I once more ask the Lord to have mercy on this suffering world in which he chose to dwell as one of us. May he pour out the treasures of his light and love, so that our world, which presses forward despite wars, socio-economic disparities and uses of technology that threaten our humanity, may regain the most important and necessary thing of all: its heart.

CHAPTER TWO

ACTIONS AND WORDS OF LOVE

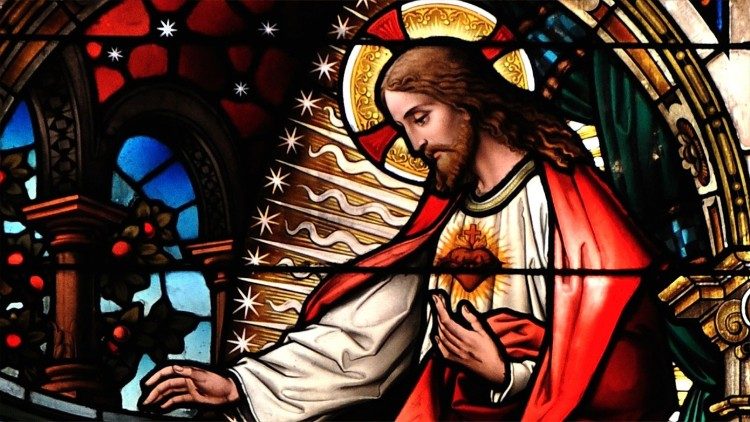

32. The heart of Christ, as the symbol of the deepest and most personal source of his love for us, is the very core of the initial preaching of the Gospel. It stands at the origin of our faith, as the wellspring that refreshes and enlivens our Christian beliefs.

ACTIONS THAT REFLECT THE HEART

33. Christ showed the depth of his love for us not by lengthy explanations but by concrete actions. By examining his interactions with others, we can come to realize how he treats each one of us, even though at times this may be difficult to see. Let us now turn to the place where our faith can encounter this truth: the word of God.

34. The Gospel tells us that Jesus “came to his own” (cf. Jn 1:11). Those words refer to us, for the Lord does not treat us as strangers but as a possession that he watches over and cherishes. He treats us truly as “his own”. This does not mean that we are his slaves, something that he himself denies: “I do not call you servants” (Jn 15:15). Rather, it refers to the sense of mutual belonging typical of friends. Jesus came to meet us, bridging all distances; he became as close to us as the simplest, everyday realities of our lives. Indeed, he has another name, “Emmanuel”, which means “God with us”, God as part of our lives, God as living in our midst. The Son of God became incarnate and “emptied himself, taking the form of a slave” (Phil 2:7).

35. This becomes clear when we see Jesus at work. He seeks people out, approaches them, ever open to an encounter with them. We see it when he stops to converse with the Samaritan woman at the well where she went to draw water (cf. Jn 4:5-7). We see it when, in the darkness of night, he meets Nicodemus, who feared to be seen in his presence (cf. Jn 3:1-2). We marvel when he allows his feet to be washed by a prostitute (cf. Lk 7:36-50), when he says to the woman caught in adultery, “Neither do I condemn you” (Jn 8:11), or again when he chides the disciples for their indifference and quietly asks the blind man on the roadside, “What do you want me to do for you?” (Mk 10:51). Christ shows that God is closeness, compassion and tender love.

36. Whenever Jesus healed someone, he preferred to do it, not from a distance but in close proximity: “He stretched out his hand and touched him” ( Mt 8:3). “He touched her hand” ( Mt 8:15). “He touched their eyes” ( Mt 9:29). Once he even stopped to cure a deaf man with his own saliva (cf. Mk 7:33), as a mother would do, so that people would not think of him as removed from their lives. “The Lord knows the fine science of the caress. In his compassion, God does not love us with words; he comes forth to meet us and, by his closeness, he shows us the depth of his tender love”. [27]

37. If we find it hard to trust others because we have been hurt by lies, injuries and disappointments, the Lord whispers in our ear: “Take heart, son!” (Mt 9:2), “Take heart, daughter!” (Mt 9:22). He encourages us to overcome our fear and to realize that, with him at our side, we have nothing to lose. To Peter, in his fright, “Jesus immediately reached out his hand and caught him”, saying, “You of little faith, why did you doubt?” (Mt 14:31). Nor should you be afraid. Let him draw near and sit at your side. There may be many people we distrust, but not him. Do not hesitate because of your sins. Keep in mind that many sinners “came and sat with him” (Mt 9:10), yet Jesus was scandalized by none of them. It was the religious élite that complained and treated him as “a glutton and a drunkard, a friend of tax collectors and sinners” (Mt 11:19). When the Pharisees criticized him for his closeness to people deemed base or sinful, Jesus replied, “I desire mercy, not sacrifice” (Mt 9:13).

38. That same Jesus is now waiting for you to give him the chance to bring light to your life, to raise you up and to fill you with his strength. Before his death, he assured his disciples, “I will not leave you orphaned; I am coming to you. In a little while the world will no longer see me, but you will see me” (Jn 14:18-19). Jesus always finds a way to be present in your life, so that you can encounter him.

JESUS’ GAZE

39. The Gospel tells us that a rich man came up to Jesus, full of idealism yet lacking in the strength needed to change his life. Jesus then “looked at him” (Mk 10:21). Can you imagine that moment, that encounter between his eyes and those of Jesus? If Jesus calls you and summons you for a mission, he first looks at you, plumbs the depths of your heart and, knowing everything about you, fixes his gaze upon you. So it was when, “as he walked by the Sea of Galilee, he saw two brothers… and as he went from there, he saw two other brothers” (Mt 4:18, 21).

40. Many a page of the Gospel illustrates how attentive Jesus was to individuals and above all to their problems and needs. We are told that, “when he saw the crowds, he had compassion for them, because they were harassed and helpless” (Mt 9:36). Whenever we feel that everyone ignores us, that no one cares what becomes of us, that we are of no importance to anyone, he remains concerned for us. To Nathanael, standing apart and busy about his own affairs, he could say, “I saw you under the fig tree before Philip called you” (Jn 1:48).

41. Precisely out of concern for us, Jesus knows every one of our good intentions and small acts of charity. The Gospel tells us that once he “saw a poor widow put in two small copper coins” in the Temple treasury (Lk 21:2) and immediately brought it to the attention of his disciples. Jesus thus appreciates the good that he sees in us. When the centurion approached him with complete confidence, “Jesus listened to him and was amazed” (Mt 8:10). How reassuring it is to know that, even if others are not aware of our good intentions or actions, Jesus sees them and regards them highly.

42. In his humanity, Jesus learned this from Mary, his mother. Our Lady carefully pondered the things she had experienced; she “treasured them… in her heart” (Lk 2:19, 51) and, with Saint Joseph, she taught Jesus from his earliest years to be attentive in this same way.

JESUS’ WORDS

43. Although the Scriptures preserve Jesus’ words, ever alive and timely, there are moments when he speaks to us inwardly, calls us and leads us to a better place. That better place is his heart. There he invites us to find fresh strength and peace: “Come to me, all who are weary and are carrying heavy burdens, and I will give you rest” (Mt 11:28). In this sense, he could say to his disciples, “Abide in me” (Jn 15:4).

44. Jesus’ words show that his holiness did not exclude deep emotions. On various occasions, he demonstrated a love that was both passionate and compassionate. He could be deeply moved and grieved, even to the point of shedding tears. It is clear that Jesus was not indifferent to the daily cares and concerns of people, such as their weariness or hunger: “I have compassion for this crowd… they have nothing to eat… they will faint on the way, and some of them have come from a great distance” (Mk 8:2-3).

45. The Gospel makes no secret of Jesus’ love for Jerusalem: “As he came near and saw the city, he wept over it” (Lk 19:41). He then voiced the deepest desire of his heart: “If you had only recognized on this day the things that make for peace” (Lk 19:42). The evangelists, while at times showing him in his power and glory, also portray his profound emotions in the face of death and the grief felt by his friends. Before recounting how Jesus, standing before the tomb of Lazarus, “began to weep” (Jn 11:35), the Gospel observes that, “Jesus loved Martha and her sister and Lazarus” (Jn 11:5) and that, seeing Mary and those who were with her weeping, “he was greatly disturbed in spirit and deeply moved” (Jn 11:33). The Gospel account leaves no doubt that his tears were genuine, the sign of inner turmoil. Nor do the Gospels attempt to conceal Jesus’ anguish over his impending violent death at the hands of those whom he had loved so greatly: he “began to be distressed and agitated” (Mk 14:33), even to the point of crying out, “I am deeply grieved, even to death” (Mk 14:34). This inner turmoil finds its most powerful expression in his cry from the cross: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Mk 15:34).

46. At first glance, all this may smack of pious sentimentalism. Yet it is supremely serious and of decisive importance, and finds its most sublime expression in Christ crucified. The cross is Jesus’ most eloquent word of love. A word that is not shallow, sentimental or merely edifying. It is love, sheer love. That is why Saint Paul, struggling to find the right words to describe his relationship with Christ, could speak of “the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me” (Gal 2:20). This was Paul’s deepest conviction: the knowledge that he was loved. Christ’s self-offering on the cross became the driving force in Paul’s life, yet it only made sense to him because he knew that something even greater lay behind it: the fact that “he loved me”. At a time when many were seeking salvation, prosperity or security elsewhere, Paul, moved by the Spirit, was able to see farther and to marvel at the greatest and most essential thing of all: “Christ loved me”.

47. Now, after considering Christ and seeing how his actions and words grant us insight into his heart, let us turn to the Church’s reflection on the holy mystery of the Lord’s Sacred Heart.

CHAPTER THREE

THIS IS THE HEART THAT HAS LOVED SO GREATLY

48. Devotion to the heart of Christ is not the veneration of a single organ apart from the Person of Jesus. What we contemplate and adore is the whole Jesus Christ, the Son of God made man, represented by an image that accentuates his heart. That heart of flesh is seen as the privileged sign of the inmost being of the incarnate Son and his love, both divine and human. More than any other part of his body, the heart of Jesus is “the natural sign and symbol of his boundless love”.[28]

WORSHIPING CHRIST

49. It is essential to realize that our relationship to the Person of Jesus Christ is one of friendship and adoration, drawn by the love represented under the image of his heart. We venerate that image, yet our worship is directed solely to the living Christ, in his divinity and his plenary humanity, so that we may be embraced by his human and divine love.

50. Whatever the image employed, it is clear that the living heart of Christ – not its representation – is the object of our worship, for it is part of his holy risen body, which is inseparable from the Son of God who assumed that body forever. We worship it because it is “the heart of the Person of the Word, to whom it is inseparably united”.[29] Nor do we worship it for its own sake, but because with this heart the incarnate Son is alive, loves us and receives our love in return. Any act of love or worship of his heart is thus “really and truly given to Christ himself”,[30] since it spontaneously refers back to him and is “a symbol and a tender image of the infinite love of Jesus Christ”.[31]

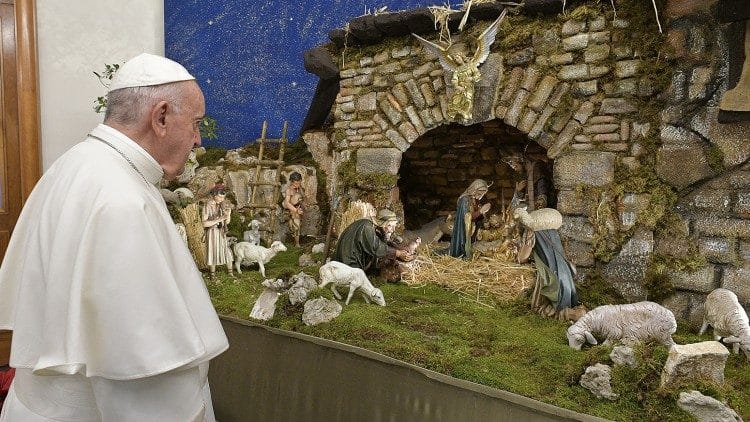

51. For this reason, it should never be imagined that this devotion may distract or separate us from Jesus and his love. In a natural and direct way, it points us to him and to him alone, who calls us to a precious friendship marked by dialogue, affection, trust and adoration. The Christ we see depicted with a pierced and burning heart is the same Christ who, for love of us, was born in Bethlehem, passed through Galilee healing the sick, embracing sinners and showing mercy. The same Christ who loved us to the very end, opening wide his arms on the cross, who then rose from the dead and now lives among us in glory.

VENERATING HIS IMAGE

52. While the image of Christ and his heart is not in itself an object of worship, neither is it simply one among many other possible images. It was not devised at a desk or designed by an artist; it is “no imaginary symbol, but a real symbol which represents the centre, the source from which salvation flowed for all humanity”.[32]

53. Universal human experience has made the image of the heart something unique. Indeed, throughout history and in different parts of the world, it has become a symbol of personal intimacy, affection, emotional attachment and capacity for love. Transcending all scientific explanations, a hand placed on the heart of a friend expresses special affection: when two persons fall in love and draw close to one another, their hearts beat faster; when we are abandoned or deceived by someone we love, our hearts sink. So too, when we want to say something deeply personal, we often say that we are speaking “from the heart”. The language of poetry reflects the power of these experiences. In the course of history, the heart has taken on unique symbolic value that is more than merely conventional.

54. It is understandable, then, that the Church has chosen the image of the heart to represent the human and divine love of Jesus Christ and the inmost core of his Person. Yet, while the depiction of a heart afire may be an eloquent symbol of the burning love of Jesus Christ, it is important that this heart not be represented apart from him. In this way, his summons to a personal relationship of encounter and dialogue will become all the more meaningful.[33] The venerable image portraying Christ holding out his loving heart also shows him looking directly at us, inviting us to encounter, dialogue and trust; it shows his strong hands capable of supporting us and his lips that speak personally to each of us.

55. The heart, too, has the advantage of being immediately recognizable as the profound unifying centre of the body, an expression of the totality of the person, unlike other individual organs. As a part that stands for the whole, we could easily misinterpret it, were we to contemplate it apart from the Lord himself. The image of the heart should lead us to contemplate Christ in all the beauty and richness of his humanity and divinity.

56. Whatever particular aesthetic qualities we may ascribe to various portrayals of Christ’s heart when we pray before them, it is not the case that “something is sought from them or that blind trust is put in images as once was done by the Gentiles”. Rather, “through these images that we kiss, and before which we kneel and uncover our heads, we are adoring Christ”.[34]

57. Certain of these representations may indeed strike us as tasteless and not particularly conducive to affection or prayer. Yet this is of little importance, since they are only invitations to prayer, and, to cite an Eastern proverb, we should not limit our gaze to the finger that points us to the moon. Whereas the Eucharist is a real presence to be worshiped, sacred images, albeit blessed, point beyond themselves, inviting us to lift up our hearts and to unite them to the heart of the living Christ. The image we venerate thus serves as a summons to make room for an encounter with Christ, and to worship him in whatever way we wish to picture him. Standing before the image, we stand before Christ, and in his presence, “love pauses, contemplates mystery, and enjoys it in silence”.[35]

58. At the same time, we must never forget that the image of the heart speaks to us of the flesh and of earthly realities. In this way, it points us to the God who wished to become one of us, a part of our history, and a companion on our earthly journey. A more abstract or stylized form of devotion would not necessarily be more faithful to the Gospel, for in this eloquent and tangible sign we see how God willed to reveal himself and to draw close to us.

A LOVE THAT IS TANGIBLE

59. On the other hand, love and the human heart do not always go together, since hatred, indifference and selfishness can also reign in our hearts. Yet we cannot attain our fulfilment as human beings unless we open our hearts to others; only through love do we become fully ourselves. The deepest part of us, created for love, will fulfil God’s plan only if we learn to love. And the heart is the symbol of that love.

60. The eternal Son of God, in his utter transcendence, chose to love each of us with a human heart. His human emotions became the sacrament of that infinite and endless love. His heart, then, is not merely a symbol for some disembodied spiritual truth. In gazing upon the Lord’s heart, we contemplate a physical reality, his human flesh, which enables him to possess genuine human emotions and feelings, like ourselves, albeit fully transformed by his divine love. Our devotion must ascend to the infinite love of the Person of the Son of God, yet we need to keep in mind that his divine love is inseparable from his human love. The image of his heart of flesh helps us to do precisely this.

61. Since the heart continues to be seen in the popular mind as the affective centre of each human being, it remains the best means of signifying the divine love of Christ, united forever and inseparably to his wholly human love. Pius XII observed that the Gospel, in referring to the love of Christ’s heart, speaks “not only of divine charity but also human affection”. Indeed, “the heart of Jesus Christ, hypostatically united to the divine Person of the Word, beyond doubt throbbed with love and every other tender affection”.[36]

62. The Fathers of the Church, opposing those who denied or downplayed the true humanity of Christ, insisted on the concrete and tangible reality of the Lord’s human affections. Saint Basil emphasized that the Lord’s incarnation was not something fanciful, and that “the Lord possessed our natural affections”.[37] Saint John Chrysostom pointed to an example: “Had he not possessed our nature, he would not have experienced sadness from time to time”.[38] Saint Ambrose stated that “in taking a soul, he took on the passions of the soul”.[39] For Saint Augustine, our human affections, which Christ assumed, are now open to the life of grace: “The Lord Jesus assumed these affections of our human weakness, as he did the flesh of our human weakness, not out of necessity, but consciously and freely… lest any who feel grief and sorrow amid the trials of life should think themselves separated from his grace”.[40] Finally, Saint John Damascene viewed the genuine affections shown by Christ in his humanity as proof that he assumed our nature in its entirety in order to redeem and transform it in its entirety: Christ, then, assumed all that is part of human nature, so that all might be sanctified.[41]

63. Here, we can benefit from the thoughts of a theologian who maintains that, “due to the influence of Greek thought, theology long relegated the body and feelings to the world of the pre-human or sub-human or potentially inhuman; yet what theology did not resolve in theory, spirituality resolved in practice. This, together with popular piety, preserved the relationship with the corporal, psychological and historical reality of Jesus. The Stations of the Cross, devotion to Christ’s wounds, his Precious Blood and his Sacred Heart, and a variety of Eucharist devotions… all bridged the gaps in theology by nourishing our hearts and imagination, our tender love for Christ, our hope and memory, our desires and feelings. Reason and logic took other directions”.[42]

A THREEFOLD LOVE

64. Nor do we remain only on the level of the Lord’s human feelings, beautiful and moving as they are. In contemplating Christ’s heart we also see how, in his fine and noble sentiments, his kindness and gentleness and his signs of genuine human affection, the deeper truth of his infinite divine love is revealed. In the words of Benedict XVI, “from the infinite horizon of his love, God wished to enter into the limits of human history and the human condition. He took on a body and a heart. Thus, we can contemplate and encounter the infinite in the finite, the invisible and ineffable mystery in the human heart of Jesus the Nazarene”.[43]

65. The image of the Lord’s heart speaks to us in fact of a threefold love. First, we contemplate his infinite divine love. Then our thoughts turn to the spiritual dimension of his humanity, in which the heart is “the symbol of that most ardent love which, infused into his soul, enriches his human will”. Finally, “it is a symbol also of his sensible love”.[44]

66. These three loves are not separate, parallel or disconnected, but together act and find expression in a constant and vital unity. For “by faith, through which we believe that the human and divine nature were united in the Person of Christ, we can see the closest bonds between the tender love of the physical heart of Jesus and the twofold spiritual love, namely human and divine”.[45]

67. Entering into the heart of Christ, we feel loved by a human heart filled with affections and emotions like our own. Jesus’ human will freely choose to love us, and that spiritual love is flooded with grace and charity. When we plunge into the depths of his heart, we find ourselves overwhelmed by the immense glory of his infinite love as the eternal Son, which we can no longer separate from his human love. It is precisely in his human love, and not apart from it, that we encounter his divine love: we discover “the infinite in the finite”.[46]

68. It is the constant and unequivocal teaching of the Church that our worship of Christ’s person is undivided, inseparably embracing both his divine and his human natures. From ancient times, the Church has taught that we are to “adore one and the same Christ, the Son of God and of man, consisting of and in two inseparable and undivided natures”.[47] And we do so “with one act of adoration… inasmuch as the Word became flesh”.[48] Christ is in no way “worshipped in two natures, whereby two acts of worship are introduced”; instead, we venerate “by one act of worship God the Word made flesh, together with his own flesh”.[49]

69. Saint John of the Cross sought to explain that in mystical experience the infinite love of the risen Christ is not perceived as alien to our lives. The infinite in some way “condescends” to enable us, through the open heart of Christ, to experience an encounter of truly reciprocal love, for “it is indeed credible that a bird of lowly flight can capture the royal eagle of the heights, if this eagle descends with the desire of being captured”.[50] He also explains that the Bridegroom, “beholding that the bride is wounded with love for him, because of her moan he too is wounded with love for her. Among lovers, the wound of one is the wound of both”.[51] John of the Cross regards the image of Christ’s pierced side as an invitation to full union with the Lord. Christ is the wounded stag, wounded when we fail to let ourselves be touched by his love, who descends to the streams of water to quench his thirst and is comforted whenever we turn to him:

“Return, dove!

The wounded stag

is in sight on the hill,

cooled by the breeze of your flight”.[52]

TRINITARIAN PERSPECTIVES

70. Devotion to the heart of Jesus, as a direct contemplation of the Lord that draws us into union with him, is clearly Christological in nature. We see this in the Letter to the Hebrews, which urges us to “run with perseverance the race that is set before us, looking to Jesus” (12:2). At the same time, we need to realize that Jesus speaks of himself as the way to the Father: “I am the way… No one comes to the Father except through me” (Jn 14:6). Jesus wants to bring us to the Father. That is why, from the very beginning, the Church’s preaching does not end with Jesus, but with the Father. As source and fullness, the Father is ultimately the one to be glorified.[53]

71. If we turn, for example, to the Letter to the Ephesians, we can see clearly how our worship is directed to the Father: “I bow my knees before the Father” (3:14). There is “one God and Father of all, who is above all and through all and in all” (4:6). “Give thanks to God the Father at all times and for everything” (5:20). It is the Father “for whom we exist” (1 Cor 8:6). In this sense, Saint John Paul II could say that, “the whole of the Christian life is like a great pilgrimage to the house of the Father”.[54] This too was the experience of Saint Ignatius of Antioch on his path to martyrdom: “In me there is left no spark of desire for mundane things, but only a murmur of living water that whispers within me, ‘Come to the Father’”.[55]

72. The Father is, before all else, the Father of Jesus Christ: “Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ” (Eph 1:3). He is “the God of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Father of glory” ( Eph 1:17). When the Son became man, all the hopes and aspirations of his human heart were directed towards the Father. If we consider the way Christ spoke of the Father, we can grasp the love and affection that his human heart felt for him, this complete and constant orientation towards him. [56] Jesus’ life among us was a journey of response to the constant call of his human heart to come to the Father. [57]

73. We know that the Aramaic word Jesus used to address the Father was “Abba”, an intimate and familiar term that some found disconcerting (cf. Jn 5:18). It is how he addressed the Father in expressing his anguish at his impending death: “Abba, Father, for you all things are possible; remove this cup from me; yet, not what I want, but what you want” (Mk 14:36). Jesus knew well that he had always been loved by the Father: “You loved me before the foundation of the world” (Jn 17:24). In his human heart, he had rejoiced at hearing the Father say to him: “You are my Son, the Beloved; with you I am well pleased” (Mk 1:11).

74. The Fourth Gospel tells us that the eternal Son was always “close to the Father’s heart” (Jn 1:18).[58] Saint Irenaeus thus declares that “the Son of God was with the Father from the beginning”.[59] Origen, for his part, maintains that the Son perseveres “in uninterrupted contemplation of the depths of the Father”.[60] When the Son took flesh, he spent entire nights conversing with his beloved Father on the mountaintop (cf. Lk 6:12). He told us, “I must be in my Father’s house” (Lk 2:49). We see too how he expressed his praise: “Jesus rejoiced in the Holy Spirit and said, ‘I thank you, Father, Lord of heaven and earth’ (Lk 10:21). His last words, full of trust, were, “Father, into your hands I commend my spirit” (Lk 23:46).

75. Let us now turn to the Holy Spirit, whose fire fills the heart of Christ. As Saint John Paul II once said, Christ’s heart is “the Holy Spirit’s masterpiece”.[61] This is more than simply a past event, for even now “the heart of Christ is alive with the action of the Holy Spirit, to whom Jesus attributed the inspiration of his mission (cf. Lk 4:18; Is 61:1) and whose sending he had promised at the Last Supper. It is the Spirit who enables us to grasp the richness of the sign of Christ’s pierced side, from which the Church has sprung (cf. Sacrosanctum Concilium, 5)”.[62] In a word, “only the Holy Spirit can open up before us the fullness of the ‘inner man’, which is found in the heart of Christ. He alone can cause our human hearts to draw strength from that fullness, step by step”.[63]

76. If we seek to delve more deeply into the mysterious working of the Spirit, we learn that he groans within us, saying “Abba!” Indeed, “the proof that you are children is that God has sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, crying, ‘Abba! Father!’” (Gal 4:6). For “the Spirit bears witness with our spirit that we are children of God” (Rom 8:16). The Holy Spirit at work in Christ’s human heart draws him unceasingly to the Father. When the Spirit unites us to the sentiments of Christ through grace, he makes us sharers in the Son’s relationship to the Father, whereby we receive “a spirit of adoption through which we cry out, ‘Abba! Father!’” (Rom 8:15).

77. Our relationship with the heart of Christ is thus changed, thanks to the prompting of the Spirit who guides us to the Father, the source of life and the ultimate wellspring of grace. Christ does not expect us simply to remain in him. His love is “the revelation of the Father’s mercy”,[64] and his desire is that, impelled by the Spirit welling up from his heart, we should ascend to the Father “with him and in him”. We give glory to the Father “through” Christ,[65] “with” Christ,[66] and “in” Christ.[67] Saint John Paul II taught that, “the Saviour’s heart invites us to return to the Father’s love, which is the source of every authentic love”.[68] This is precisely what the Holy Spirit, who comes to us through the heart of Christ, seeks to nurture in our hearts. For this reason, the liturgy, through the enlivening work of the Spirit, always addresses the Father from the risen heart of Christ.

RECENT TEACHINGS OF THE MAGISTERIUM

78. In numerous ways, Christ’s heart has always been present in the history of Christian spirituality. In the Scriptures and in the early centuries of the Church’s life, it appeared under the image of the Lord’s wounded side, as a fountain of grace and a summons to a deep and loving encounter. In this same guise, it has reappeared in the writings of numerous saints, past and present. In recent centuries, this spirituality has gradually taken on the specific form of devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

79. A number of my Predecessors have spoken in various ways about the heart of Christ and exhorted us to unite ourselves to it. At the end of the nineteenth century, Leo XIII encouraged us to consecrate ourselves to the Sacred Heart, thus uniting our call to union with Christ and our wonder before the magnificence of his infinite love.[69] Some thirty years later, Pius XI presented this devotion as a “summa” of the experience of Christian faith.[70] Pius XII went on to declare that adoration of the Sacred Heart expresses in an outstanding way, as a sublime synthesis, the worship we owe to Jesus Christ.[71]

80. More recently, Saint John Paul II presented the growth of this devotion in recent centuries as a response to the rise of rigorist and disembodied forms of spirituality that neglected the richness of the Lord’s mercy. At the same time, he saw it as a timely summons to resist attempts to create a world that leaves no room for God. “Devotion to the Sacred Heart, as it developed in Europe two centuries ago, under the impulse of the mystical experiences of Saint Margaret Mary Alacoque, was a response to Jansenist rigor, which ended up disregarding God’s infinite mercy… The men and women of the third millennium need the heart of Christ in order to know God and to know themselves; they need it to build the civilization of love”.[72]

81. Benedict XVI asked us to recognize in the heart of Christ an intimate and daily presence in our lives: “Every person needs a ‘centre’ for his or her own life, a source of truth and goodness to draw upon in the events, situations and struggles of daily existence. All of us, when we pause in silence, need to feel not only the beating of our own heart, but deeper still, the beating of a trustworthy presence, perceptible with faith’s senses and yet much more real: the presence of Christ, the heart of the world”.[73]

FURTHER REFLECTIONS AND RELEVANCE FOR OUR TIMES

82. The expressive and symbolic image of Christ’s heart is not the only means granted us by the Holy Spirit for encountering the love of Christ, yet it is, as we have seen, an especially privileged one. Even so, it constantly needs to be enriched, deepened and renewed through meditation, the reading of the Gospel and growth in spiritual maturity. Pius XII made it clear that the Church does not claim that, “we must contemplate and adore in the heart of Jesus a ‘formal’ image, that is, a perfect and absolute sign of his divine love, for the essence of this love can in no way be adequately expressed by any created image whatsoever”.[74]

83. Devotion to Christ’s heart is essential for our Christian life to the extent that it expresses our openness in faith and adoration to the mystery of the Lord’s divine and human love. In this sense, we can once more affirm that the Sacred Heart is a synthesis of the Gospel.[75] We need to remember that the visions or mystical showings related by certain saints who passionately encouraged devotion to Christ’s heart are not something that the faithful are obliged to believe as if they were the word of God.[76] Nonetheless, they are rich sources of encouragement and can prove greatly beneficial, even if no one need feel forced to follow them should they not prove helpful on his or her own spiritual journey. At the same time, however, we should be mindful that, as Pius XII pointed out, this devotion cannot be said “to owe its origin to private revelations”.[77]

84. The promotion of Eucharistic communion on the first Friday of each month, for example, sent a powerful message at a time when many people had stopped receiving communion because they were no longer confident of God’s mercy and forgiveness and regarded communion as a kind of reward for the perfect. In the context of Jansenism, the spread of this practice proved immensely beneficial, since it led to a clearer realization that in the Eucharist the merciful and ever-present love of the heart of Christ invites us to union with him. It can also be said that this practice can prove similarly beneficial in our own time, for a different reason. Amid the frenetic pace of today’s world and our obsession with free time, consumption and diversion, cell phones and social media, we forget to nourish our lives with the strength of the Eucharist.

85. While no one should feel obliged to spend an hour in adoration each Thursday, the practice ought surely to be recommended. When we carry it out with devotion, in union with many of our brothers and sisters and discover in the Eucharist the immense love of the heart of Christ, we “adore, together with the Church, the sign and manifestation of the divine love that went so far as to love, through the heart of the incarnate Word, the human race”.[78]

86. Many Jansenists found this difficult to comprehend, for they looked askance on all that was human, affective and corporeal, and so viewed this devotion as distancing us from pure worship of the Most High God. Pius XII described as “false mysticism”[79] the elitist attitude of those groups that saw God as so sublime, separate and distant that they regarded affective expressions of popular piety as dangerous and in need of ecclesiastical oversight.

87. It could be argued that today, in place of Jansenism, we find ourselves before a powerful wave of secularization that seeks to build a world free of God. In our societies, we are also seeing a proliferation of varied forms of religiosity that have nothing to do with a personal relationship with the God of love, but are new manifestations of a disembodied spirituality. I must warn that within the Church too, a baneful Jansenist dualism has re-emerged in new forms. This has gained renewed strength in recent decades, but it is a recrudescence of that Gnosticism which proved so great a spiritual threat in the early centuries of Christianity because it refused to acknowledge the reality of “the salvation of the flesh”. For this reason, I turn my gaze to the heart of Christ and I invite all of us to renew our devotion to it. I hope this will also appeal to today’s sensitivities and thus help us to confront the dualisms, old and new, to which this devotion offers an effective response.

88. I would add that the heart of Christ also frees us from another kind of dualism found in communities and pastors excessively caught up in external activities, structural reforms that have little to do with the Gospel, obsessive reorganization plans, worldly projects, secular ways of thinking and mandatory programmes. The result is often a Christianity stripped of the tender consolations of faith, the joy of serving others, the fervour of personal commitment to mission, the beauty of knowing Christ and the profound gratitude born of the friendship he offers and the ultimate meaning he gives to our lives. This too is the expression of an illusory and disembodied otherworldliness.

89. Once we succumb to these attitudes, so widespread in our day, we tend to lose all desire to be cured of them. This leads me to propose to the whole Church renewed reflection on the love of Christ represented in his Sacred Heart. For there we find the whole Gospel, a synthesis of the truths of our faith, all that we adore and seek in faith, all that responds to our deepest needs.

90. As we contemplate the heart of Christ, the incarnate synthesis of the Gospel, we can, following the example of Saint Therese of the Child Jesus, “place heartfelt trust not in ourselves but in the infinite mercy of a God who loves us unconditionally and has already given us everything in the cross of Jesus Christ”. [80] Therese was able to do this because she had discovered in the heart of Christ that God is love: “To me he has granted his infinite mercy, and through it I contemplate and adore the other divine perfections”. [81] That is why a popular prayer, directed like an arrow towards the heart of Christ, says simply: “Jesus, I trust in you”. [82] No other words are needed.

91. In the following chapters, we will emphasize two essential aspects that contemporary devotion to the Sacred Heart needs to combine, so that it can continue to nourish us and bring us closer to the Gospel: personal spiritual experience and communal missionary commitment.

CHAPTER FOUR

A LOVE THAT GIVES ITSELF AS DRINK

92. Let us now return to the Scriptures, the inspired texts where, above all, we encounter God’s revelation. There, and in the Church’s living Tradition, we hear what the Lord has wished to tell us in the course of history. By reading several texts from the Old and the New Testaments, we will gain insight into the word of God that has guided the great spiritual pilgrimage of his people down the ages.

A GOD WHO THIRSTS FOR LOVE

93. The Bible shows that the people that journeyed through the desert and yearned for freedom received the promise of an abundance of life-giving water: “With joy you will draw water from the wells of salvation” (Is 12:3). The messianic prophecies gradually coalesced around the imagery of purifying water: “I will sprinkle clean water upon you, and you shall be clean… a new spirit I will put within you” (Ezek 36:25-26). This water would bestow on God’s people the fullness of life, like a fountain flowing from the Temple and bringing a wealth of life and salvation in its wake. “I saw on the bank of the river a great many trees on the one side and on the other… and wherever that river goes, every living creature will live… and when that river enters the sea, its waters will become fresh; everything will live where the river goes” (Ezek 47:7-9).

94. The Jewish festival of Booths ( Sukkot), which recalls the forty-year sojourn of Israel in the desert, gradually adopted the symbolism of water as a central element. It included a rite of offering water each morning, which became most solemn on the final day of the festival, when a great procession took place towards the Temple, the altar was circled seven times and the water was offered to God amid loud cries of joy. [83]

95. The dawn of the messianic era was described as a fountain springing up for the people: “I will pour out a spirit of compassion and supplication on the house of David and the inhabitants of Jerusalem, and they shall look on him whom they have pierced… On that day, a fountain shall be opened for the house of David and the inhabitants of Jerusalem, to cleanse them from sin and impurity” (Zech 12:10; 13:1).

96. One who is pierced, a flowing fountain, the outpouring of a spirit of compassion and supplication: the first Christians inevitably considered these promises fulfilled in the pierced side of Christ, the wellspring of new life. In the Gospel of John, we contemplate that fulfilment. From Jesus’ wounded side, the water of the Spirit poured forth: “One of the soldiers pierced his side with a spear, and at once blood and water flowed out” (Jn 19:34). The evangelist then recalls the prophecy that had spoken of a fountain opened in Jerusalem and the pierced one (Jn 19:37; cf. Zech 12:10). The open fountain is the wounded side of Christ.

97. Earlier, John’s Gospel had spoken of this event, when on “the last day of the festival” (Jn 7:37), Jesus cried out to the people celebrating the great procession: “Let anyone who is thirsty come to me and drink… out of his heart shall flow rivers of living water” (Jn 7:37-38). For this to be accomplished, however, it was necessary for Jesus’ “hour” to come, for he “was not yet glorified” (Jn 7:39). That fulfilment was to come on the cross, in the blood and water that flowed from the Lord’s side.

98. The Book of Revelation takes up the prophecies of the pierced one and the fountain: “every eye will see him, even those who pierced him” (Rev 1:7); “Let everyone who is thirsty come; let anyone who wishes take the water of life as a gift” (Rev 22:17).

99. The pierced side of Jesus is the source of the love that God had shown for his people in countless ways. Let us now recall some of his words:

“Because you are precious in my sight and honoured, I love you” (Is 43:4).

“Can a woman forget her nursing child, or show no compassion for the child of her womb? Even if these may forget, yet I will not forget you. See, I have inscribed you on the palms of my hands” (Is 49:15-16).

“For the mountains may depart, and the hills be removed, but my steadfast love shall not depart from you, and my covenant of peace shall not be removed” (Is 54:10).

“I have loved you with an everlasting love; therefore I have continued my faithfulness to you” (Jer 31:3).

“The Lord, your God, is in your midst, a warrior who gives you victory; he will rejoice over you with gladness, he will renew you in his love; he will exult over you with loud singing” (Zeph 3:17).

100. The prophet Hosea goes so far as to speak of the heart of God, who “led them with cords of human kindness, with bands of love” (Hos 11:4). When that love was spurned, the Lord could say, “My heart is stirred within me; my compassion grows warm and tender (Hos 11:8). God’s merciful love always triumphs (cf. Hos 11:9), and it was to find its most sublime expression in Christ, his definitive Word of love.

101. The pierced heart of Christ embodies all God’s declarations of love present in the Scriptures. That love is no mere matter of words; rather, the open side of his Son is a source of life for those whom he loves, the fount that quenches the thirst of his people. As Saint John Paul II pointed out, “the essential elements of devotion [to the Sacred Heart] belong in a permanent fashion to the spirituality of the Church throughout her history; for since the beginning, the Church has looked to the heart of Christ pierced on the Cross”. [84]

ECHOES OF THE WORD IN HISTORY

102. Let us consider some of the ways that, in the history of the Christian faith, these prophecies were understood to have been fulfilled. Various Fathers of the Church, especially those in Asia Minor, spoke of the wounded side of Jesus as the source of the water of the Holy Spirit: the word, its grace and the sacraments that communicate it. The courage of the martyrs is born of “the heavenly fount of living waters flowing from the side of Christ” [85] or, in the version of Rufinus, “the heavenly and eternal streams that flow from the heart of Christ”. [86] We believers, reborn in the Spirit, emerge from the cleft in the rock; “we have come forth from the heart of Christ”. [87] His wounded side, understood as his heart, filled with the Holy Spirit, comes to us as a flood of living water. “The fount of the Spirit is entirely in Christ”. [88] Yet the Spirit whom we have received does not distance us from the risen Lord, but fills us with his presence, for by drinking of the Spirit we drink of the same Christ. In the words of Saint Ambrose: “Drink of Christ, for he is the rock that pours forth a flood of water. Drink of Christ, for he is the source of life. Drink of Christ, for he is the river whose streams gladden the city of God. Drink of Christ, for he is our peace. Drink of Christ, for from his side flows living water”. [89]

103. Saint Augustine opened the way to devotion to the Sacred Heart as the locus of our personal encounter with the Lord. For Augustine, Christ’s wounded side is not only the source of grace and the sacraments, but also the symbol of our intimate union with Christ, the setting of an encounter of love. There we find the source of the most precious wisdom of all, which is knowledge of him. In effect, Augustine writes that John, the beloved disciple, reclining on Jesus’ bosom at the Last Supper, drew near to the secret place of wisdom. [90] Here we have no merely intellectual contemplation of an abstract theological truth. As Saint Jerome explains, a person capable of contemplation “does not delight in the beauty of that stream of water, but drinks of the living water flowing from the side of the Lord”. [91]

104. Saint Bernard takes up the symbolism of the pierced side of the Lord and understands it explicitly as a revelation and outpouring of all of the love of his heart. Through that wound, Christ opens his heart to us and enables us to appropriate the boundless mystery of his love and mercy: “I take from the bowels of the Lord what is lacking to me, for his bowels overflow with mercy through the holes through which they stream. Those who crucified him pierced his hands and feet, they pierced his side with a lance. And through those holes I can taste wild honey and oil from the rocks of flint, that is, I can taste and see that the Lord is good… A lance passed through his soul even to the region of his heart. No longer is he unable to take pity on my weakness. The wounds inflicted on his body have disclosed to us the secrets of his heart; they enable us to contemplate the great mystery of his compassion”. [92]

105. This theme reappears especially in William of Saint-Thierry, who invites us to enter into the heart of Jesus, who feeds us from his own breast. [93] This is not surprising if we recall that for William, “the art of arts is the art of love… Love is awakened by the Creator of nature, and is a power of the soul that leads it, as if by its natural gravity, to its proper place and end”. [94] That proper place, where love reigns in fullness, is the heart of Christ: “Lord, where do you lead those whom you embrace and clasp to your heart? Your heart, Jesus, is the sweet manna of your divinity that you hold within the golden jar of your soul (cf. Heb 9:4), and that surpasses all knowledge. Happy those who, having plunged into those depths, have been hidden by you in the recess of your heart”. [95]

106. Saint Bonaventure unites these two spiritual currents. He presents the heart of Christ as the source of the sacraments and of grace, and urges that our contemplation of that heart become a relationship between friends, a personal encounter of love.

107. Bonaventure makes us appreciate first the beauty of the grace and the sacraments flowing from the fountain of life that is the wounded side of the Lord. “In order that from the side of Christ sleeping on the cross, the Church might be formed and the Scripture fulfilled that says: ‘They shall look upon him whom they pierced’, one of the soldiers struck him with a lance and opened his side. This was permitted by divine Providence so that, in the blood and water flowing from that wound, the price of our salvation might flow from the hidden wellspring of his heart, enabling the Church’s sacraments to confer the life of grace and thus to be, for those who live in Christ, like a cup filled from the living fount springing up to life eternal”. [96]

108. Bonaventure then asks us to take another step, in order that our access to grace not be seen as a kind of magic or neo-platonic emanation, but rather as a direct relationship with Christ, a dwelling in his heart, so that whoever drinks from that source becomes a friend of Christ, a loving heart. “Rise up, then, O soul who are a friend of Christ, and be the dove that nests in the cleft in the rock; be the sparrow that finds a home and constantly watches over it; be the turtledove that hides the offspring of its chaste love in that most holy cleft”. [97]

THE SPREAD OF DEVOTION TO THE HEART OF CHRIST

109. Gradually, the wounded side of Christ, as the abode of his love and the wellspring of the life of grace, began to be associated with his heart, especially in monastic life. We know that in the course of history, devotion to the heart of Christ was not always expressed in the same way, and that its modern developments, related to a variety of spiritual experiences, cannot be directly derived from the mediaeval forms, much less the biblical forms in which we glimpse the seeds of that devotion. This notwithstanding, the Church today rejects nothing of the good that the Holy Spirit has bestowed on us down the centuries, for she knows that it will always be possible to discern a clearer and deeper meaning in certain aspects of that devotion, and to gain new insights over the course of time.

110. A number of holy women, in recounting their experiences of encounter with Christ, have spoken of resting in the heart of the Lord as the source of life and interior peace. This was the case with Saints Lutgarde and Mechtilde of Hackeborn, Saint Angela of Foligno and Dame Julian of Norwich, to mention only a few. Saint Gertrude of Helfta, a Cistercian nun, tells of a time in prayer when she reclined her head on the heart of Christ and heard its beating. In a dialogue with Saint John the Evangelist, she asked him why he had not described in his Gospel what he experienced when he did the same. Gertrude concludes that “the sweet sound of those heartbeats has been reserved for modern times, so that, hearing them, our aging and lukewarm world may be renewed in the love of God”. [98] Might we think that this is indeed a message for our own times, a summons to realize how our world has indeed “grown old”, and needs to perceive anew the message of Christ’s love? Saint Gertrude and Saint Mechtilde have been considered among “the most intimate confidants of the Sacred Heart”. [99]

111. The Carthusians, encouraged above all by Ludolph of Saxony, found in devotion to the Sacred Heart a means of growth in affection and closeness to Christ. All who enter through the wound of his heart are inflamed with love. Saint Catherine of Siena wrote that the Lord’s sufferings are impossible for us to comprehend, but the open heart of Christ enables us to have a lively personal encounter with his boundless love. “I wished to reveal to you the secret of my heart, allowing you to see it open, so that you can understand that I have loved you so much more than I could have proved to you by the suffering that I once endured”. [100]

112. Devotion to the heart of Christ slowly passed beyond the walls of the monasteries to enrich the spirituality of saintly teachers, preachers and founders of religious congregations, who then spread it to the farthest reaches of the earth. [101]

113. Particularly significant was the initiative taken by Saint John Eudes, who, “after preaching with his confrères a fervent mission in Rennes, convinced the bishop of that diocese to approve the celebration of the feast of the Adorable Heart of our Lord Jesus Christ. This was the first time that such a feast was officially authorized in the Church. Following this, between the years 1670 and 1671, the bishops of Coutances, Evreux, Bayeux, Lisieux and Rouen authorized the celebration of the feast for their respective dioceses”. [102]

SAINT FRANCIS DE SALES

114. In modern times, mention should be made of the important contribution of Saint Francis de Sales. Francis frequently contemplated Christ’s open heart, which invites us to dwell therein, in a personal relationship of love that sheds light on the mysteries of his life. In his writings, the saintly Doctor of the Church opposes a rigorous morality and a legalistic piety by presenting the heart of Jesus as a summons to complete trust in the mysterious working of his grace. We see this expressed in his letter to Saint Jane Francis de Chantal: “I am certain that we will remain no longer in ourselves… but dwell forever in the Lord’s wounded side, for apart from him not only can we do nothing, but even if we were able, we would lack the desire to do anything”. [103]

115. For Francis de Sales, true devotion had nothing to do with superstition or perfunctory piety, since it entails a personal relationship in which each of us feels uniquely and individually known and loved by Christ. “This most adorable and lovable heart of our Master, burning with the love which he professes to us, [is] a heart on which all our names are written… Surely it is a source of profound consolation to know that we are loved so deeply by our Lord, who constantly carries us in his heart”. [104] With the image of our names written on the heart of Christ, Saint Francis sought to express the extent to which Christ’s love for each of us is not something abstract and generic, but utterly personal, enabling each believer to feel known and respected for who he or she is. “How lovely is this heaven, in which the Lord is its sun and his breast a fountain of love from which the blessed drink to their heart’s content! Each of us can look therein and see our name carved in letters of love, which true love alone can read and true love has written. Dear God! And what too, beloved daughter, of our loved ones? Surely they will be there too; for even if our hearts have no love, they nonetheless possess a desire for love and the beginnings of love”. [105]