Are You Holy?

A Call to Work on Daily

“Are You Holy?” is the title of Father Raul Ortiz Toros’ article, a priest of the Archdiocese of Ibagué, Colombia, and Director of the Department of Doctrine and Promotion of Unity and of the Dialogue of the Colombian Episcopal Conference, in which he reflects on holiness.

* * *

Generally, when I ask a person: are you holy? They usually open their eyes in the sign of admiration and, somewhat confused, answer radically: “No.” We have been taught that a Saint doesn’t sin, doesn’t walk on the tortuous paths of human frivolities: from egoism to a smile. Because a Saint, according to the imaginary, can’t have fun, not even in a healthy way, because it’s not seen as right. There is a whole ideology around holiness, which has hindered us from believing the truth, that we have been called to it. Vatican Council II expressed it solemnly in number 40 of the Constitution Lumen Gentium (Light of the Nations ): “All the faithful, of any state or condition, are called to the fulness of the Christian life and to the perfection of charity, and this holiness arouses a more human level of life, including in the earthly society. “ Listening to the Council, we can say that all of us, from the moment of our Baptism, have a call to holiness that we must work on in daily living, with the beautiful objective of reaching a more human level of life.

A bit further on, the Council summarizes holiness in the duty to “dedicate ourselves with our whole soul to the glory of God and the service of our neighbour. But, in the first place, what is the glory of God? Saint Irenaeus said (in Adversus Haereses, 4, 20, 7) that the glory of God is the living man,” namely, us, as image and likeness of God, are His glory and, in the measure that we approach the ideal of Christ we discover the grace that the Lord transmits to us. In specific terms, we don’t “give” glory to God, as we cannot give anything to the Creator, but we are His glory in the measure in which we make ourselves “Christiform,” that is: that we offer our sufferings, forgive those that offend us, live the Beatitudes, etc. The second exigency of holiness is to be at the service of our neighbor, to see Christ’s face in people, from those that bother us to those we love profoundly, to serve them with love and, like the Lord, “heal their wounds with the oil of consolation and with the wine of hope,” as the Common Preface VIII refers to in the Roman Missal.

Finally, I want to end with the words of Saint John Paul II in the Audience of March 23, 1983, which summarizes this topic wonderfully: “Christian sanctity doesn’t consist in being impeccable, but in the struggle not to yield, and to get up again always, after each fall. And it doesn’t stem so much from man’s will power, but rather from the effort not to ever hinder the action of grace in one’s soul and to be, instead, its humble collaborators.”

What lovely words these are, full of consolation and hope. A Saint is not someone who never sins, but someone who is able to accepts his human limitations, who puts himself in God’s hands, and cries out, like Peter in the stormy sea: “Lord, save me” (Matthew 14:30) and is determined to take the necessary measures in his life not to let himself sink.

The Solemnity of All Saints (November 1) is an invitation to live holiness, which many have assumed in their lives. Saint Augustine said: “Why can I not do what these men and women were able to do?” Found in the Communion of Saints are those Saints declared such by the Church as well as the anonymous Saints, so many people with the Heart of Christ who pass into eternity manifesting to the world the glory of God and helping their neighbor. There is also a place for us there, given our effort to be saints, hence, it’s our feast too.

Translation by Virginia M. Forrester

Related

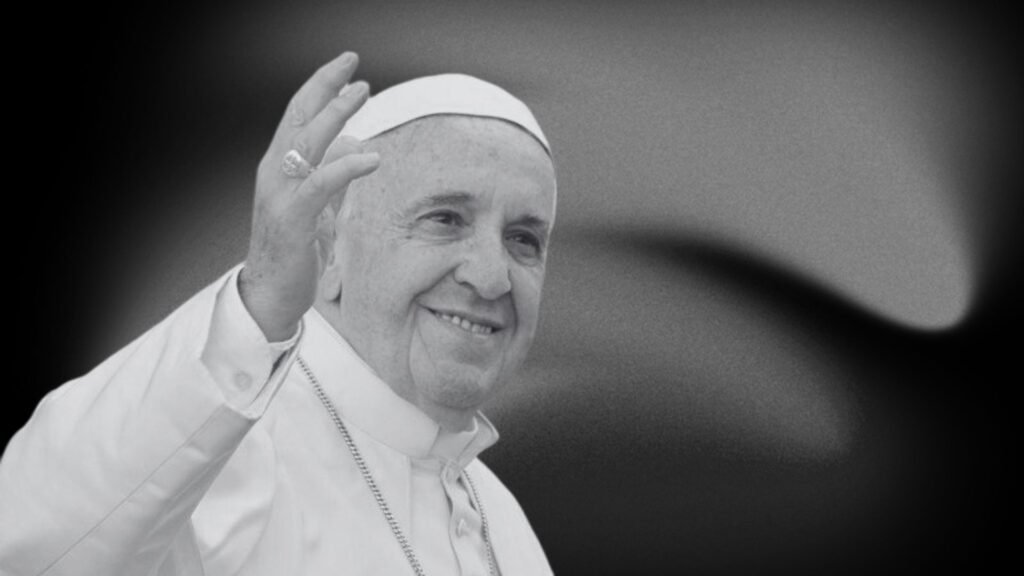

Saying Goodbye to Francis

Exaudi Staff

26 April, 2025

2 min

The Family: A School of Love, Forgiveness, and Hope

Laetare

25 April, 2025

3 min

Pope Francis: Leadership That Transforms Through Service

Javier Ferrer García

25 April, 2025

4 min

The heart of the Church beats between mourning and hope

Exaudi Staff

24 April, 2025

2 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)