Archbishop Gallagher to UN Trade Group

'From Inequality and Vulnerability to Prosperity for All'

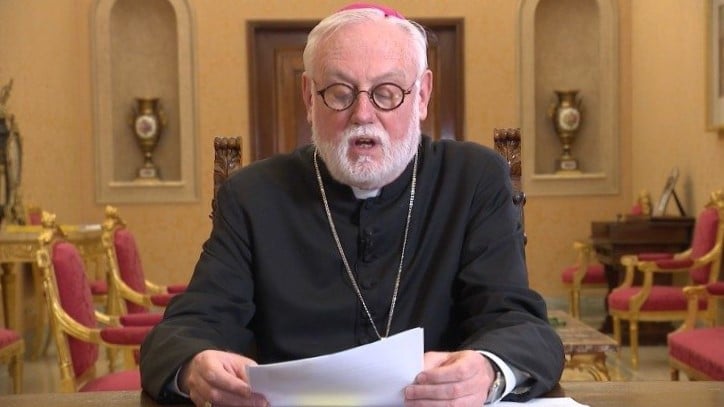

The following is the statement given this morning by Archbishop Paul Richard Gallagher, Secretary for Relations with States, on the occasion of the XV Ministerial Conference of UNCTAD, “From inequality and vulnerability to prosperity for all”, taking place in Bridgetown, Barbados from October 3-7, 2021:

Intervention of Archbishop Paul Richard Gallagher

Statement by His Excellency Archbishop Paul Richard Gallagher

Secretary for Relations with States at the XV Ministerial Conference of UNCTAD

“From inequality and vulnerability to prosperity for all”

Bridgetown, 5 October 2021

Madam President,

At the outset, the Holy See wishes to thank the Government of Barbados for virtually hosting this Ministerial Conference. We also would like to express our sincere congratulations to Ms. Rebecca Grynspan for her appointment as UNCTAD Secretary-General. Surely, the States convened in this Ministerial Conference maintain a firm conviction that our historic collaboration will result in the advancement of the core focus of this Conference: “Prosperity for all”.

The Covid-19 global situation has led to the most severe recession since World War II. While the pandemic has affected everyone, its fallout, in terms of health and livelihoods, has disproportionately affected people with the greatest vulnerabilities. Even in high-income countries, the economic impact has varied widely. Those with digital skills and financial assets made gains, while those without such resources fell further behind, and women, young people and migrants were hit the hardest. The damage in developing countries, where fiscal space is constrained, was greater still, with poverty levels and food insecurity rising despite years of progress in these domains. Thus, the pandemic has dramatically exposed existing fault-lines and fragilities in the prevailing economic model. As Pope Francis has noted, this is a model that “strengthens the identity of the more powerful, who can protect themselves, but it tends to diminish the identity of the weaker and poorer regions, making them more vulnerable and dependent. In this way, political life becomes increasingly fragile in the face of transnational economic powers that operate with the principle of ‘divide and conquer,” (Fratelli tutti, n. 12)

In addition, extreme inequality has re-emerged as a prevailing feature of the contemporary world. Many factors can explain the progressive deterioration of this scenario, both within and across countries. Technological change and high-speed (hyper) globalization have contributed to a decrease in real wages for workers as well as to accelerated deindustrialization, laying waste to many manufacturing centers. Nonetheless, technology alone can hardly explain changes of the magnitude witnessed over the past decades. The unregulated financial markets and institutions with short-term horizons have been a catalytic factor behind these trends.

The emergency generated by the pandemic has challenged, but not eliminated, this attitude. As wages have decreased, millions of individuals have been plunged into poverty, and this has set back poverty reduction targets by nearly a decade. The fault lines of the global economy, in fact, have been dramatically exposed. Moreover, those already in vulnerable situations, people who were facing serious financial challenges prior to the pandemic, were disproportionately affected by its fallout.

Responses to the interrelated dimensions of inequalities

This crisis provides a unique opportunity for sustainable change. In the current scenario, even worse than the crisis itself, would be the tragedy of squandering potential lessons learned by closing in on ourselves. The human family has an opportunity “to go beyond short-term technological or financial fixes and take full account of the ethical dimension in seeking solutions to current problems or propose initiatives for the future”, aiming at authentic integral human development that can only be achieved “when all members of the human family are included in the search for the common good and can contribute to it”,1 as stated by Pope Francis. Moving in this direction and making substantial advancement in economic and social inclusion, however, will require important policy and regulatory shifts in several areas.

First, fighting rampant inequality cannot be achieved without fiscal redistribution and increasing the progressiveness of income taxation schedules. Adequate enforcement of corporate taxation, especially multinational enterprises (MNEs), is equally important. Better taxation can redistribute a portion of the rents accruing to big corporations and help build up tax bases, especially in developing countries. Nonetheless, this does not solve structural problems, such as the persistent productivity gap between small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and large firms, which is an important driver of the observed rise in inequality, including wage inequality.

The COVID-19 pandemic not only has increased inequality within countries, but it has also upended public budgets in many developing economies, exposing their sovereign debts to global financial instability. These economies have faced more limitations than developed countries in their efforts to mobilize domestic fiscal resources to respond to the pandemic. This, too, is one more example of the dangerous global divide between the haves and the have-nots. One first step in overcoming this divide was made by the decision of the G20 and the Paris Club to suspend bilateral debt service repayments for a select number of vulnerable developing countries. A much more ambitious multilateral approach to debt restructuring and relief is needed. This should aim at substantial redemption schedules for public external debts of developing economies, along with expanding the use of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) and Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) to support national development strategies. As stated by Pope Francis, “it is important that ethics once again play its due part in the world of finance and that markets serve the interests of peoples and the common good of humanity2”. In fact, we should reaffirm that facilitating good global governance is an essential ingredient for an international environment capable of promoting sustainable development.

A more ambitious approach and rebalancing of the multilateral system are also needed to enable developing countries to harness policy space for structural transformation and convergence. Inequality, in fact, further blocks their successful integration into the global economy. Strengthening international cooperation and providing every country with the adequate means to cope with the current challenges would represent an investment in systemic resilience.

Health and access to medications and vaccines is yet another area characterized by significant inequalities that could pose significant repercussions in the future and dangerous risks for systemic resilience. In the rapidly evolving pandemic scenario, a waiver on World Trade Organization (WTO) intellectual property rules, as proposed by South Africa and India, and supported from the very beginning by the Holy See, would be a vital and necessary step to end this pandemic, by enabling adequate and rapid access to vaccines, diagnostics and treatments for all countries. In particular, given the different technologies and challenges related to COVID-19 vaccines, such a waiver should be combined with ensuring the open sharing of vaccine know-how and technology.

Finally, in the quest for climate stabilization and climate justice, necessary investment in decarbonization of our economies and making sufficient funds available to achieve this end, represent an opportunity to channel resources toward those areas in greater need of industrial restructuring. In addition, it is crucial that we find ways to reconcile climate, industrial and social policy within a strategic and integral perspective. In view of the current climate trends, transformation to a more sustainable economy requires enhancing the ability of countries and economies to adapt to higher temperatures, thus necessitating a better understanding of how trade and development will be affected by a warmer world. Mitigation and adaptation are two sides of the same coin in the fight against global warming, and they need to be complemented by facilitating adequate implementation in developing countries.

Conclusion

The extreme inequality that has emerged in recent decades is underpinned by an individualistic ideology that has abandoned the notion of the common good in a common home with common horizons. Investment and prosperity have been delinked from notions of a social contract and a commitment to a caring society; rather, today they are perceived merely from the perspective of sources of profit. Pope Francis warned that “[r]adical individualism is a virus that is extremely difficult to eliminate, for it is clever. It makes us believe that everything consists in giving free rein to our own ambitions, as if by pursuing ever greater ambitions and creating safety nets we would somehow be serving the common good” (Fratelli tutti, 105).

In this context, mutual debt has become the glue that holds our increasingly segmented and anxious communities together. However, as more and more households, firms and governments have become dependent on borrowing against a backdrop of slow productivity growth, stagnant wages, and precarious employment, debt has turned into a solvent, corroding the trust and solidarity on which a fair and healthy society depends.

A new ethics of the common good is necessary. It forms the basis for policy-making capable of both tackling the structural inequalities behind our deeply divided and increasingly fragile world and unleashing the spirit of human ingenuity and creativity, which is urgently needed to build back better from the devastation of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Such an ethical approach to development has to be embodied in a new multilateral architecture that would allow us to turn the page on years of selfishness and loss of civic values and culture. Over the last four decades, hyper-globalization has represented the guiding narrative of international relations, in which the territorial power of strong States has become intertwined with the extra-territorial power of large footloose corporations. As a consequence, the international community has been completely unable (or, even worse, unwilling) to put forward comprehensive proposals to alleviate the difficulties of poorer countries and, in particular, of the poorest communities.

Given the overwhelming impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the call for a global partnership for sustainable development goes well beyond the moral commitment to “leave no one behind”. In an increasingly interconnected world, it also must be rooted in long-term consideration and action related to global public goods, potential spillovers across nations, and, ultimately, to the world’s systemic resilience. In line with this, it is now time to recover the notion of interdependence and to re-build multilateralism around the ideals of social justice and mutual responsibility among and within nations. Only in this way can we hope to calibrate the global economy toward a twenty-first-century vision of stability, shared prosperity, and environmental sustainability, and ensure a resilient and prosperous future for all.

Madam President,

Seventy-six years ago, a sense of international solidarity, collective action (and sacrifice), as well as local efforts provided the inspiration and motivation for those tasked with building a better post-conflict world. In that context, prosperity was considered as essential as peace and ensuring one was deemed necessary to achieve the other. Guided by this vision and these principles, States participating in the first U.N. Conference on Trade and Development in Geneva expressed their determination “to seek a better and more effective system of international economic co-operation, whereby the division of the world into areas of poverty and plenty may be banished and prosperity achieved by all.” They called for the abolition of poverty everywhere and saw it as essential “that the flows of world trade should help to eliminate the wide economic disparities among nations…The task of development,” they added, “is for the benefit of the people as a whole.”3

Without UNCTAD, dialogue and consensus-building between developing and developed countries would have been less rich, effective, and meaningful. In a world more and more interdependent, as shown by the effects of the current pandemic, the role of UNCTAD remains valid and necessary if we want to maximize the advantages of globalization and minimize its negative consequences. The Holy See believes, therefore, that this Conference should remain committed to its ideals, and thus focus on how the international community can ensure that UNCTAD plays its full and meaningful role in support of the new global development agenda, with particular attention to the needs of poor countries and of poor people. The crisis that is paralyzing the WTO provides strong evidence that the stakes in this Conference are higher than ever before. UNCTAD ought to seize this timely opportunity to reaffirm the centrality of multilateralism and to relaunch the dialogue on real reforms in trade, finance and development. This would mark a significant and necessary change of pace.

Thank you, Madam President.

____________________

1 Message of Pope Francis to the World Economic Forum, 21 January 2021. Available at hiips://press.vatican.va/content/salastampa/it/bollettino/pubblico/2020/01/21/0038/00083.html

2 Address of Pope Francis to the participants in the Conference on impact investing for the poor, Rome 16 June 2014. Available at: hiips://w2.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/speeches/2014/june/documents/papa- francesco_20140616_convegno-justpeace.html

3 Final Act of UNCTAD I, adopted on June 15, 1964. Preamble, §§1, 4.

Related

He who is without sin, let him cast the first stone: Fr. Jorge Miró

Jorge Miró

06 April, 2025

3 min

Reflection by Bishop Enrique Díaz: Great things you have done for us, Lord

Enrique Díaz

06 April, 2025

5 min

“The priest finds his reason for being in the Eucharist”

Fundación CARF

01 April, 2025

5 min

Family Valued: An international appeal for the family

Exaudi Staff

01 April, 2025

2 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)