Archbishop Dermot Farrell Homily, Day of Consecrated Life

'Occasion to Thank the Lord for the Gift of Lives Given to God'

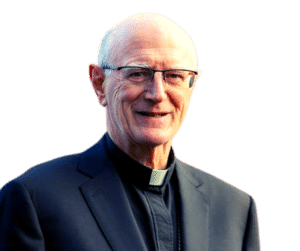

Archbishop Dermot Farrell, Archbishop of Dublin, preached the homily below on February 5, 202, to observe the World Day of Consecrated Life. The Mass was celebrated at the Redemptoristine Monastery, Iona Road, Dublin.

***

Every year the Church celebrates the World Day of Consecrated Life. It is an occasion to thank the Lord for the gift of lives given to God—lifetimes of service, of commitment to the service of the gospel and the mission of the Church, and of prophetic witness to the presence and significance of Jesus. It is also an occasion to pray for you, to bring you—and with you the Church—to the Lord who “called you—and us all—out of darkness into his own marvelous light,” as the First Letter of Peter so hopefully puts it (1Pet 2:9).

The sixth chapter of John’s Gospel culminates in the presentation of Jesus as the bread of life. Opening with the feeding of the five thousand, St John presents us with Jesus who responds to the multitude in their hunger and need. The bread he gives is bread from heaven, Manna in the desert, the bread of liberation and life: the hope of the Exodus made tangible again. And so Jesus addresses not only the multitude’s most immediate need but also believing, drawing near, and listening. What he has to say binds the most distant hope—eternal life—with who and what he is: “unless you eat …” Many of his disciples—perhaps most of them—“left him and stopped going with him” (6:66). In character, Jesus challenges the Twelve: he turns to them, and asks if they too wish to go? This is symbolic of the choice that faces every person of faith, and a fortiori those in religious life.

Peter’s response, “to whom shall we go, you have the words of eternal life,” could be seen as the response of someone who has run out of options, but it is much more, the response of someone who has come to see who and what is essential. In the often conflicting and confusing claims about what it means to be a religious today, Peter’s realization offers an optic for what lies at the heart of religious life. The commitment of Peter and his companions to Jesus did not wipe away all their issues or weaknesses. Our commitment to the Lord will not wipe away all our issues or our weaknesses. God’s gift of God’s very self is free; it is a grace, but the welcome of that gift comes at a cost. Real gifts have real consequences. Illusory gifts—in whatever form—are not gift at all! In the end, they enslave. The German martyr Dietrich Bonhoeffer saw this clearly: in the 1930s he railed against the illusion that is ‘cheap’ grace. He named it, lived it, and it cost him his life: “Cheap grace is the preaching of forgiveness without requiring repentance, baptism without church discipline, communion without confession, absolution without personal confession. Cheap grace is grace without discipleship, grace without the cross, grace without Jesus Christ, living and incarnate” (Cost of Discipleship (London: SCM, 1959), 4).

This is a road we must all tread, a place to which we must all come: “to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life.” This very day, Jesus puts the same question—and the answer can only come in freedom, from the heart. Although Peter’s answer isn’t the most high-minded, it comes straight from his heart, as it always does. Peter too is in character! I suppose at the heart of the matter is that Peter and Jesus have come to a knowledge of each other. Peter—impetuous, impulsive, Jesus patient. In the end, Jesus is more committed to Peter, than Peter is to Jesus. And that is the heart of the matter. Jesus “is not pretentious. Our complications fall away before his simplicity. His gentleness and mercy may bowl us over, but we can be ourselves with him—and with his Father—more than anywhere else” [Maria Boulding, The Coming of God, 130–31].

Is it any different for us? What motived Peter and the apostles—not a large group—to remain was that they had arrived at a trust in the Lord: they came to love him. Even today that is the crucial decision. You and I have remained with Christ because we believe that he has the words of life—words that we must share with those who have left us. Not without cost, as Bonhoeffer would say, not without the cross, as the Lord put it and lived it. We stayed, and have never regretted it, as many of you yourselves will say.

If the Lord had been evaluating the suitability of Peter, Philip, or Judas on their human strengths, gift and talents, it is unlikely any of them would have made the cut. Of course, these human traits have to be taken into account. But there is another question, one proper to any form of Christian ministry: is this woman or man weak enough to be a minister of the gospel? This is particularly true in times of failure, pain and desolation. The question addressed to Philip by Jesus, “where can we buy some bread for these people to eat?” comes to mind when we face the impossible. Philip is aware of his powerlessness in the situation. Yet, it is clear from the Gospel that in trying to cope with the situation he was dependent on his own power, rather than on the power of God. The real strength of religious life and ministry lies in the weakness that seems to threaten them. Like Christ, we are called to enter deeply into human suffering.

After suffering a devastating stroke that left him debilitated, Pedro Arrupe offered this to his Jesuit colleagues gathered at the thirty-third General Congregation: “More than ever, I find myself in the hands of God. This is what I have wanted all my life, from my youth. And this is still the one thing I want. But now there is a difference: the initiative is entirely with God. It is indeed a profound spiritual experience to know and feel myself so totally in God’s hands” (Pedro Arrupe, Essential Writings, Orbis 2004, p 201).

St Paul saw his own journey in a series of setbacks or sufferings, as connecting moments of weakness, but transformed through the power of Christ: “‘My grace is enough for you: for power is at the full in weakness.’ So I am happy to boast about my weaknesses so that the power of Christ may dwell in me; therefore, I am content with weaknesses, insults, constraints, persecutions, and distress for Christ’s sake. For whenever I am weak, then I am strong” (2 Cor 12:9-10). Making a decision for the Lord is not easier today than it was in the time of Paul or Jesus. The choice to devote our entire life to the Lord is never logical or rational when such commitment may bring with it painful difficulties.

When asked if they too wanted “to go away”, Peter answered Jesus, “Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life.” Christ has given himself to us, and Christ gives himself to us every day. He gives himself to us today. To him, we may go today. Christ says, “I am the way, the truth, and the life,” (John 14:6) not I was the way, the truth, and the life. His promise is today. “Today, these words are fulfilled in your hearing.” (Luke 4:21) The vocation to religious life is not the giving of obedience to an object, but to the faithfulness and love of the Lord Jesus for every person, particularly in our weakness.

This perspective might permit us to hear afresh and with new hope what the Holy Father put before religious women and men on this day three years ago: “Consecrated life is not about survival, it is not about preparing ourselves for dying well: this is the temptation of our days, in the face of declining vocations. No, it is not about survival, but new life. … But there are only a few of us, it’s about new life. It is a living encounter with the Lord in his people. It is a call to the faithful obedience of daily life and to the unexpected surprises from the Spirit. It is a vision of what we need to embrace in order to experience joy: Jesus” (Pope Francis, Homily, Day of Prayer for Consecrated Life, 2nd February 2019).

Today, I thank God for the wisdom and experience, the generosity and prayer, of the women and men whom the Lord has called to consecrate their lives in love of Him and in the service of their sisters and brothers. Since you are determined and committed to making the Good News relevant to today’s changing world, your mission does not belong to the past. Despite the reduced numbers of those in religious, and your decisions to withdraw from places where your work of service is clearly visible, you are not invisible to us, to the Archdiocese, or to the world. Like the presence of Christ himself, your presence has changed: your very ‘being’ people who are consecrated are of immense value and are greatly appreciated. In building up the body of Christ through their charisms and in their lives (1 Cor 12:12-30) the 2,500 religious women and men from 54 countries today are carrying out their mission creatively and selflessly in the Archdiocese: in responding to the cry of refugees, of migrants and of other vulnerable groups, in responding to the cry of the earth, as they strive to promote change, while at the same time endeavoring to deepen the spirituality of people through their ministry of prayer and witness. How much poorer would the Diocese (or Church) be without the tireless service of these consecrated men and woman in religious, monastic, and contemplative institutes, secular institutes and new institutes, hermits, consecrated virgins and members of societies and apostolic life who willingly give to our faithful and support those in diocesan ministry—the priests, deacons, and laity?

In the June of 1965, in the early years of his pontificate, Pope Paul VI wrote his ‘spiritual Testament. His prayer for his diocese of Rome was

May you ever be mindful of the mystery of your vocation;

may you may be able to fulfill, with human virtue and with Christian faith,

your spiritual and universal mission,

however long may be the history of the world.”

May his words and the vibrant faith, humility, and hope from which they sprang still inspire us today. May we always encourage one another in this effort.

+Dermot Farrell,

Archbishop of Dublin

Related

I have ardently desired to eat this Passover with you: Fr. Jorge Miró

Jorge Miró

12 April, 2025

2 min

Pope Francis Sends a Message of Hope to the Young People of the UNIV 2025 International Congress

Exaudi Staff

11 April, 2025

5 min

“Highway to Heaven” Arrives in Rome: Carlo Acutis’ Musical Evangelizes with Art and Heart

Exaudi Staff

09 April, 2025

2 min

University of the Holy Cross: A Day on Lay Holiness

Wlodzimierz Redzioch

08 April, 2025

3 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)