Code of Canon Law: New Crimes and Clearer Penalties

Press Conference to Present Changes in Book VI

A press conference was held today at 11:30 am to present the changes to Book VI of the Code of Canon Law, made by Pope Francis in the Apostolic Constitution Pascite Gregem Dei.

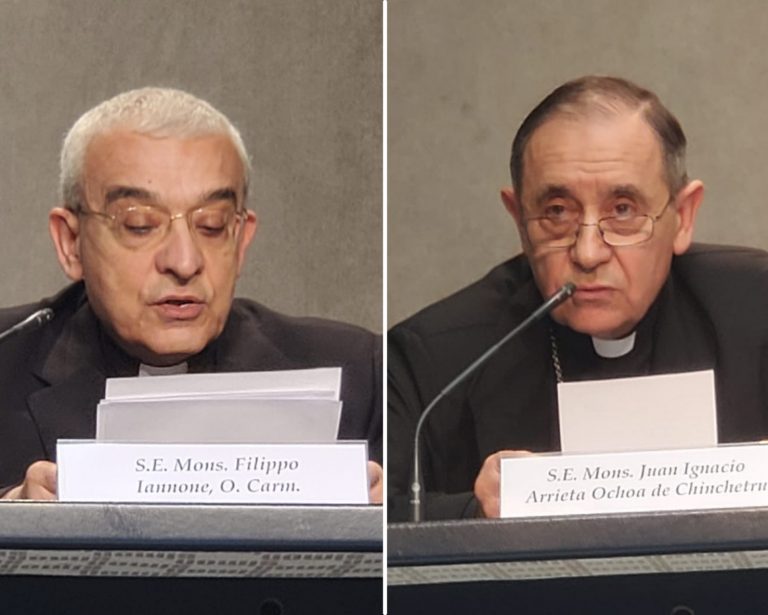

Taking part in the presentation were Monsignor Filippo Iannone, President of the Pontifical Council for the Interpretation of Legislative Texts, and Monsignor Juan Ignacio Arrieta Ochoa de Chinchetru, Secretary of the said Council. In his intervention, Monsignor Iannone recalled that this reform of the legal sanctions in the Church will come into force on December 8, Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception.

Pastors’ Responsibility

The President of the Pontifical Council for Texts also explained that Book VI is one of the seven Books that make up the Code of Canon Law, and he highlighted how Pope Francis “reiterates the importance of the observance of the laws for an ordered ecclesial life; and, consequently, claims the necessity to intervene in case of its violation” Respect and observance of criminal discipline concerns all the People of God; however, responsibility for its correct application — as said above — corresponds specifically to Pastors and Superiors of each community. It’s a commitment that belongs indisputably to the munus pastorale that is entrusted to them, and which must be exercised as a concrete and indisputable exigency of charity before the Church, before the Christian community and eventual victims, and also in relation with the one who committed a crime, who is in need at the same time of the Church’s mercy and correction (Cf. Pascite Gregem Dei).”

Monsignor Iannone also pointed out that “it is charity in fact that exacts that Pastors take recourse to the penal system as often as necessary, taking into account the three ends that make it necessary, namely, the re-establishment of the demands of justice, the amendment of the delinquent and reparation of the scandals.”

Justice and Mercy

He also said that in the last years “the rapport between justice and mercy has been badly interpreted at times, which has fuelled an atmosphere of laxity in the application of criminal law, in the name of an unfounded opposition between pastoral care and law, and criminal law in particular.” Thus, “the presence in the heart of communities of some irregular situations, but above all the recent scandals arising from the disconcerting and very grave episodes of pederasty, have led, however, to the necessity of reinvigorating canonical criminal law, integrating it with specific legislative reforms.”

Therefore, this reform, “which is presented today as necessary and long-awaited, has as objective to make universal criminal rules be increasingly adequate for the protection of the common good and the individual faithful, more congruent with the demands of justice and more effective and adequate in the present ecclesial context, which is evidently different from that of the ‘70s, time in which the canons of Book VI — abrogated today –, were elaborated.”

The reformed legislation hopes to “respond, precisely, to this necessity, offering Ordinaries and Judges an agile and useful tool, simpler and clearer rules, to foster recourse to criminal law when necessary, so that, respecting the demands of justice, faith and charity may grow in the People of God.”

Infractions and Penalties

The new criminal law has introduced “new criminal infractions and has configured other crimes already foreseen, sanctioning them also with different penalties. Moreover, new crimes have been introduced in the economic-financial realm” so that “absolute transparency is always pursued and respected in the Church’s institutional activities, especially in this realm, and that the conduct of all those holding institutional offices and all those that take part in the administration of goods is always exemplary (Cf. Address for the Inauguration of the Judicial Year of the Tribunal of Vatican City State, March 27, 2021).”

Foreseen in addition are new penalties, “such as fines, compensation for damages and prejudices, privation of all or part of ecclesiastical remuneration, according to the rules established by each Episcopal Conference, without prejudice to the obligation — in the case that the penalty is imposed on a cleric, to procure that he is not lacking what is necessary for his honest sustenance.” Attention was paid “to the enumeration of the penalties in a more ordered and detailed way, so that the Ecclesiastical Authority can identify the most appropriate and proportioned to each crime, and the possibility has been established to apply the penalty of suspension to all the faithful, and now no longer to the clerics alone. Also foreseen are “more adequate means of intervention to correct and prevent crimes. “Finally, the Prefect highlighted the “explicit affirmation in the text of the fundamental principle of the presumption of innocence and the change in the norm or prescription to foster the conclusion of the judgments in a reasonably short term.”

Crimes

He also pointed out that the crimes reserved to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith have also been included in Book VI, and changes have been made “in the denomination of the titles of the parts and chapters in which the Book is divided, and the transfer of some canons has occurred.

The Prelate mentioned as example “the transfer of the canons regarding the crime of sexual abuse of minors and crimes of child pornography from the chapter on ‘crimes against special obligations’ to that of ‘crimes against life, the dignity and the liberty of man,’” as expression “of the will of the lawmaker to reaffirm the gravity of this crime and care of the victims.” Added to it is that these crimes “are extended now in the Code also to members of Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life, and to lay faithful who enjoy a dignity or hold a position or carry out a function in the Church.”

Finally, Monsignor Iannone said that justice “exacts in these cases that the violated order be re-established, that the victim be eventually compensated and that the one who has erred be sanctioned and his offence be expiated.” However, on concluding the Constitution, the Pope reminded that the “criminal rules, as all canonical rules, must always refer to the supreme rule in force in the Church, the salus animarum. Therefore, he promulgates the text ‘with the hope that it will be an instrument for the good of souls.’”

Reasons for the Reform

Monsignor Juan Ignacio Arrieta Ochoa de Chinchetru, Secretary of the Pontifical Council explained, in the first place, the reasons for the reform. “Verified in the years immediately after the promulgation of the 1983 Code of Canon Law was that the criminal discipline contained in Book VI did not respond to the expectations it had aroused (. . .). “The new texts were often indeterminate, precisely because it was thought that the Bishops and Superiors, whose task it was to apply the criminal discipline, would decide better when and how to sanction in the most appropriate way,” but experience “showed right away the difficulties of the Ordinaries to apply the criminal rules in the midst of such lack of determination, to which was added the concrete difficulty of many of them to combine the demands of charity with those required by justice. Moreover, the difference in reactions on the part of the Authorities was also a reason for disconcert in the Christian community.”

In these circumstances, “the Holy See saw the need to supply with its own authority the deficiencies of the ordinary penalty system provided, reserving for itself exceptionally — already sine 1988, although effectively only from 2001 — the direction of the criminal discipline in cases of greater gravity.”

Development of Works

In regard to the trajectory of the works, Monsignor Arrieta Ochoa recalled that the mentioned general text led Benedict XVI “to entrust formally to the Pontifical Council for the Interpretation of Legislative Texts the beginning of the revision of Book VI of the Code of Canon Law” and, created immediately, was “a group of study in the Dicastery with expert canonists in criminal law, thus initiating the working meetings that took place over twelve years.”

The work of revision of Book VI “was carried out in the framework of a very ample collegiate collaboration and of continuous exchange of suggestions and observations, in which a large number of people worldwide took part. The work of the study group in Rome was always shared with a larger group of canonists. Having achieved a first scheme, in the summer of 2011 it was sent to all the Episcopal Conferences, to the Dicasteries of the Roman Curia, to the Major Superiors of the Institutes of Consecrated Life, to the Faculties of Canon Law, to all the Consultants and to a large number of canonists.” “More than 150 very exhaustive opinions emerged” from this consultation, which, after being systematized, were useful for the group’s later work, until reaching at the middle of the year 2016, a new amended scheme.”

Then, continued the Prelate, “a period of reflection opened to analyze if it was necessary to introduce or not even more radical changes to the text. After new studies, the opinion prevailed that it was not possible at that time to introduce more changes.” Other consultations with Dicasteries and Consultants

“led to improving the text, which was approved by the Dicastery’s Plenary Assembly on January 20, 2020.” This document, with some additional adjustments, primarily in economic matters, was fixed definitively by the Pontifical Council and submitted to the attention of the Holy Father, who signed the Apostolic Constitution on the Solemnity of Pentecost, establishing its promulgation. As a result of the work, of the 89 canons that make up this Book VI, 63 have been changed (71%), an additional 9 have bee transferred (10%) and only 17 remain without changes (19%).”

Three Orientation Criteria

The Secretary pointed out that the changes introduced in the new Book VI respond basically to three guiding criteria. In the first place, “the text now contains an adequate specification of the criminal rules that did not exist before, to give a precise and certain orientation to those that must apply them.” In order to guarantee as well a uniform use of the criminal rule in the whole Church, “the new rules have reduced the ambit of discretion, which before was left to the authority, without doing away altogether the necessary discretion required by some types of especially great crimes, which require the Pastor’s discernment on each occasion.” Moreover, “’the crimes are specified better, distinguishing cases that before, instead, were grouped together; the penalties are now enumerated exhaustively in canon 1336, and the text gives in all parts parameters to guide the evaluations of those that must judge the concrete circumstances.

The second criterion that preceded the reform, “is the protection of the community and the care given to the reparation of the scandal and compensation for the damage.” The new proposals “seek to have the instrument of the criminal sanction be a part of the ordinary form of pastoral government of communities, avoiding the elusive and deterrent formulas that existed before. Concretely, the new texts invite to impose a penal precept (c. 1319 paragraph 2 CIC), or initiate the sanctioning procedure (c. 1341), as long as the authority considers it prudently necessary or when he has verified that justice cannot be sufficiently re-established, to amend the offender or repair the scandal by other means (c. 1341).”

It is “an exigency of caritas pastorlis, which is then reflected in different new elements of the penal system and, in particular, in the necessity to repair the scandal and damage caused, to condone a punishment or postpone its application.” In general terms, “canon 1361 paragraph 4 begins saying that ‘remission must not be given until, in keeping with the prudent discretion of the Ordinary, the offender has repaired that damage, perhaps, caused.’”

Finally, the third objective pursued is that of “equipping the Pastor with the necessary means to be able to prevent crimes and intervene in time, to correct situations that could get worse, without giving up because of it the necessary precautions for the protection of the alleged delinquent, in order to guarantee what canon 1321 paragraph 1 establishes now: ‘every person is considered innocent as long as the contrary is not demonstrated.”

On the other hand, he said, “although the use of the sanctioning administrative procedure had to be accepted instead of the judicial process, the necessity is stressed to observe in these cases all the demands of the right to defense and to reach moral certainty in regard to the final decision, as well as the authority’s obligation, which had to be accepted as inevitable to maintain the same attitude of independence that canon 1342 paragraph 3 CIC exacts of the judge.”

Another instrument given the Ordinary for the prevention of crimes is the whole of penal remedies now configured in Book VI: admonition, reprehension, penal precept and vigilance. Vigilance was not foreseen before and the penal precept now receives a special regulation. It’s not about properly penal sanctions, which also be used without prior specific procedure, but always respecting the prescriptions established for the emanation of administrative acts.”

New Criminal Cases

Reorganized in this reform are the criminal causes grouped in the second part of Book VI, “transferring canons and reorienting the meaning of the epigraphs of the unique titles for the sake of better systematics.” In this connection, “crimes typified over the last years have been incorporated in special laws, such as the attempt to ordain women; the recording of confessions; the sacrilegious consecration of the Eucharistic species.”

Incorporated likewise are some present cases in the Codex of 1917, which were not accepted in 1983. “For example, corruption in the exercise of office, the administration of the Sacraments to individuals to whom it is prohibited to administer them, the concealing from the legitimate authority of eventual irregularities or censures in the reception of Sacred Orders.”

To these are added some new cases, for instance, “the violation of the papal secret; the omission of the obligation to carry out a sentence or penal decree; the omission of the obligation to notify the Commission of a crime; the illegitimate abandonment of the ministry. In particular, crimes have been typified of a patrimonial character, such as the alienation of ecclesiastical goods without the prescribed consultations; or crimes against property committed by grave fault or grave negligence in the administration.” Typified in addition is “a new crime that is foreseen for the cleric or religious that, ‘in addition to the cases already foreseen by the law, commits a crime in economic matters or gravely violates the prescriptions indicted in c. 285, paragraph 4, ‘which prohibits clerics from administering goods without the permission of their Ordinary.”

Finally, the last novelty the Prelate highlighted “the crime of abuse of minors, which is now framed not in crimes against the special obligations of clerics, but as a crime committed against the dignity of the person.” The new canon 1398 includes actions done” not only by clerics that, as we know, belong to the jurisdiction reserved to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, but also the crime of this type committed by religious who are not clerics and by laymen that have specific functions in the Church, as well as any behavior of this type with adult persons, but committed with violence or abuse of authority.”

Related

Mass in Commemoration of the 20th Anniversary of the Death of John Paul II

Exaudi Staff

01 April, 2025

1 min

Five Years After Statio Orbis: Hope in the Midst of the Storm

Exaudi Staff

27 March, 2025

2 min

St. Peter’s Dome Will Have New Lighting for Easter

Exaudi Staff

20 March, 2025

1 min

In St. Peter’s Basilica, the ancient rite of the “Statio Lenten” (Lent Station)

Exaudi Staff

17 March, 2025

2 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)