Social Distancing in the Assembly

Beyond Gestures: How the Place We Choose at Mass Speaks of Our Faith

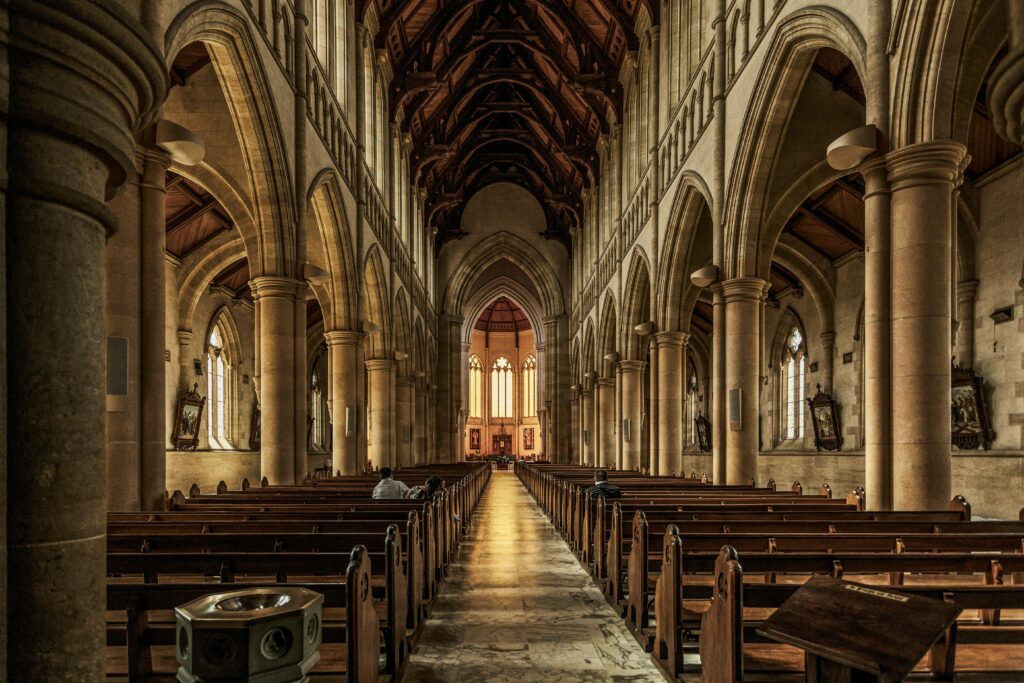

The liturgy and its rubrics speak of body postures and gestures, but they do not refer to the place occupied in the space of the church, nor to the metric distance between the faithful.

However, the place we occupy, the closeness or distance from other brothers and sisters, is also a language that could indicate proximity, fraternity, and other significant attitudes in the Eucharistic celebration.

What can most attract attention in a community is how highly valued the last seats are, those closest to the door, which are usually occupied first, even when the rest of the church is empty.

The celebrant may feel a sense of isolation, for example, when he or she has empty pews in front of him while the assembly gathers at the end.

Others prefer those corners where they can see without being seen. Columns, in this sense, are also valued.

It would be interesting to study the reasons why we choose one place or another, because just as the words we say engage us, our gestures and position in the assembly also reveal what we are experiencing at that moment.

The issue of space has been extensively studied since the middle of the last century, leading to the coining of terms such as “social distancing” or “public distancing.”

Social distancing refers to the space created to delimit physical and/or emotional contact with other people in social situations. The intensity and frequency of this type of distance will depend on the person’s qualities. Regarding physical contact, the average social distance ranges between 1.25 and 2 meters during periods of closeness, while during periods of distance it is 2 to 3.5 meters. Sharing a bench could be indicative of proximity.

In one of the comedy videos I made to alleviate the forced isolation caused by Covid-19, I spoke ironically about how we were already social distancing in my parish, even before the pandemic. No one approached anyone unless they were from the same family.

Indeed, we should probably talk about Public Distancing. Public Distancing is a concept used to address social situations in which there is little physical and emotional contact. This idea corresponds to the fact that people choose to maintain an even greater distance than that encompassed by social distancing, resulting in a noticeable lack of closeness.

In the early 1960s, the American anthropologist Edward T. Hall (1914-2009) studied and, in a way, defined “proxemics,” the science of physical distance between people and its meaning in interactions. That is, proxemics delves into individuals’ use and perception of their own physical space, their personal intimacy, and how and with whom they share it.

For Hall, public distancing has two stages: the proximal phase and the distant phase. In the first, the distance ranges between 3.5 and 7.25 meters. In the distant phase, it is greater than 7.25 meters. In other words, these are sporadic interactions in which there is no lasting dialogue between people.

Can we speak of community, family, fraternity, when, in the Eucharistic celebration, we strive to maintain this social distance, which indicates distance and ignorance?

During the pandemic, it was advised that the moment of peace be given without physical contact, with a slight bow of the head. In my parish and many others, this way of giving the peace has been established. Therefore, even for this moment, it is not necessary to get close.

The most striking thing is when, once strategic places are occupied, more people begin to arrive, and we see movements to get away from those who have “invaded” the social space we used to occupy. On certain occasions, there’s a certain excuse when the one “invading” our space is a family with infants, and those young people are far away from us. It’s hard to praise the Lord for generous families, for the innocence of children, and for the integration of Mass within the family.

It’s even more painful, if possible, to see these movements when the person approaching is of a different ethnicity and culture than ours. There, distance becomes a language of estrangement.

We are reminded of the oldest reference to the Eucharist, 1 Corinthians 11:21-34, from which we quote a fragment. … 21 For when eating, each one takes his own supper first; and one goes hungry, and another gets drunk. 22 What? Do you have no houses to eat and drink in? Or do you despise the church of God and shame those who have nothing? What shall I say to you? Shall I praise you? In this I will not praise you. 23 For I received from the Lord what I also delivered to you: that the Lord Jesus, on the night he was betrayed, took bread, …

When our old Europe receives immigrants from other latitudes who come to rejuvenate our assemblies, it should be an occasion to rejoice in their presence and bridge the gap by showing welcome.

The other is a treasure. Coming out of our walls to meet one another, even if it requires an initial effort, has the reward of gaining brothers and sisters.

Pope Francis told us, introducing the Jubilee Year at the end of 2024, referring to the motto: “Pilgrims of Hope,” that one of the paths to this hope is that of fraternity: “Yes, the hope of the world is in fraternity!”

Related

Syncretism and the Relativization of Faith: The Challenge of Religious Relativism in a Pluralist World

Javier Ferrer García

11 April, 2025

5 min

Do I Know How to Exercise Authority Over My Children?

José María Contreras

11 April, 2025

2 min

The Value of Humility at Work

José Miguel Ponce

10 April, 2025

2 min

Cardinal Arizmendi: Beware of Artificial Intelligence!

Felipe Arizmendi

09 April, 2025

5 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)