Ratzinger and the Philosophers

Ratzinger's Thought in Dialogue with the Great Philosophers of History

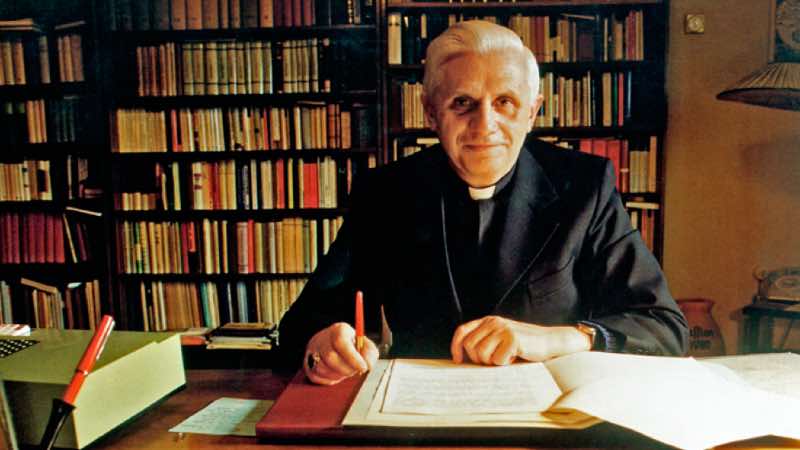

Joseph Ratzinger engaged in dialogue with philosophers in many of his theological writings. The collective book Ratzinger and the Philosophers: From Plato to Vattimo (Encuentro, 2023), edited by Alejandro Sada, Albino de Assunção, and Tracy Rowland, fully fulfills its purpose of offering a panoramic view of this dialogue. I enjoyed this lengthy reading of the text. Many of the philosophers reviewed were familiar to me; others were not. In all cases, the authors selected have produced a quality work that captures the intellectual encounter between Ratzinger and the great Western philosophers. I briefly select some of these dialogues.

Greek philosophy has provided the very foundations of Christian theology, without being bound by a particular philosophy or system. In his Introduction to Christianity, Ratzinger points out how Christianity, in its historical beginnings, sought to engage in dialogue with Greek philosophy and not with the other religions of the time. It is the Christian Logos that enters into conversation with the Greek Logos, at the moment when the latter has made the leap from myth to reason. In a particular way, “for Ratzinger, Plato is more than a historical reference point for understanding the history of Christianity: he is an interlocutor with the potential to shape the future of Europe” (p. 31). From him, he borrows the concept of anamnesis to refer to conscience, understood as a primordial memory anchored in the order of creation. A recent book by Ratzinger, La conciencia la desnuda (CTEA, 2024), compiles some of his contributions to this topic.

Bonaventure and Thomas Aquinas are present in Ratzinger’s research. The importance he placed on truth in his academic writings and papal teachings is well known. Referring to the centrality of truth in Ratzinger’s theology, Pablo Blanco points out that “if [theology] wishes to demonstrate its fidelity to the practical content of the Gospel—the salvation of man—it must be, above all, scientia speculative and cannot be directly a scientia practica. ‘It must postulate the primacy of truth, of a truth that rests on itself and whose very being must be questioned first and foremost, even before assessing its practical usefulness for human endeavors.’ Theology must recover the primacy of logos over ethos, of orthodoxy over ortho praxis, and this position—he concludes—is fundamentally found both in Thomas Aquinas and in Bonaventure (p. 97).” Logos and Caritas, reason and love, go hand in hand in Ratzinger’s thought.

Faith turns to reason, without being swallowed up by it, as Euclides Eslava rightly points out in the chapter dedicated to Auguste Comte: “Thinking about faith “is always a reflection on what has previously been heard and received.” Another characteristic of the positivism of the Christian faith is the “supremacy of the announced word over the idea, such that it is not the idea that creates the words, but rather the preached word that points the way to thought” (p. 154). Listening, receiving. It is not faith against reason, but rather a dialogue with a broader rationality. “The pontiff’s key argument is that the human world of freedom and history necessarily transcends all scientific predictions. Freedom cannot be reduced to a deterministic analysis” (p. 163). A determinism, rightly, that flutters among those who want to cage and control the future. Freedom does not allow itself to be trapped by futurologists or planners. The future cannot be unfuturized, nor can it be trapped in strategic planning.

Ratzinger shares important themes with Hegel: the idea of Greek thought at the beginning of Christianity, the importance of history and the inculturation of faith, and the centrality of community. Regarding this last point, Eduardo Chapenel points out that, in line with Hegel and “in contrast to Kierkegaard or Schleiermacher, faith for Ratzinger is not something that can truly be lived from a strictly individual level. He explains in the Introduction to Christianity that faith does not result from individual thoughts and mediation, but is the product of dialogue with others, of listening to them and receiving their ideas (p. 143).” That is to say, Kierkegaard’s “he alone before God and forever” is essential, but this intimacy to which his philosophy tends – understandable in his criticism of Hegel – minimizes the importance of the community dimension of religion and the role of the Church itself, a central theme in Ratzinger’s ecclesiology.

Thematic similarity with Hegel and also a distance from his thought. He criticizes Hegel’s excessive rationalism: reason devours religion. This perfectly rational explanation of God, developed by Hegel, did not go unnoticed by his disciple Feuerbach—of the Hegelian left—who drew the obvious conclusion: homo homini Deus, man for man is God. Hegel’s system is so rationally rounded that God is superfluous; everything is explained by reason alone: the real is rational and the rational is real. God is superfluous; in any case, he is reduced to an idea created by man.

Another important philosopher is Nietzsche. “In Ratzinger’s writings,” Owen Vyner notes, “three areas of substantial dialogue with this thinker can be found. First, in relation to Christianity and eros; second, and in conjunction with the above, Ratzinger addresses Nietzsche’s characterization of Christianity as a “capital crime against life”; Finally, regarding Nietzsche’s well-known statement on the death of God (p. 187). In his encyclical Deus Caritas Est, he exposes the inadequacy of Nietzsche’s first two criticisms of Christianity. Love is not only Eros (sensuality), it is also agapé (outpouring): both dimensions give fullness to love.

Vyner highlights “the importance of agapé, the love of self-sacrifice, which allows eros to achieve its inherent dynamism as desire. Moreover, Benedict argues, the person acts most genuinely as themselves when they do so in line with their psychosomatic unity, that is, when their body and soul are intimately united. Consequently, far from denigrating the value of the body (as is often claimed), Christianity affirms it, since the body—precisely in its sexual differentiation—becomes the possessor and foundation of the expression of true desire (p. 192).” Christianity is not, therefore, the spoilsport that eliminates the joy of life, as Nietzsche claimed; rather, it restores joy to the celebration of life.

With existentialism, there is also a rich counterpoint of ideas. Ratzinger, Conor Sweeney asserts, “in a 2001 speech attributes the following to Heidegger as much as to Jaspers: ‘They say: Faith excludes philosophy, real inquiry, and the search for ultimate realities, for it believes it already knows all this. With its certainty, it leaves no room for questioning.’” In a sort of twist on Kant’s famous words, Heidegger denies faith to make room for questioning. Clearly, by any conventional measure, for Heidegger, faith and reason must be kept categorically separate, with absolute priority for the latter (p. 21).” This chasm between the two wings through which one accesses Truth is unsustainable. Ratzinger responds to this objection, noting that “the novelty of faith is not that it closes off questioning, but that it places the interlocutor in the condition of a belief through which a deeper form of questioning can begin (p. 291).”

Sartre, on the other hand, has his own voice in the way he understands the dimensions of the human condition: nature, freedom, truth, responsibility. For Sartre, man is nothing other than what he makes himself. There is no nature or prior design of the human that can be taken as a starting point and reference; there would only be freedom. “When one focuses solely on the freedom of the individual,” Alejandro Sada summarizes Ratzinger’s thought, “one fails to take into consideration that this freedom is found in a network of mutual dependence and that this structure of intertwined freedoms is a source of obligations and responsibilities, on the fulfillment of which depends the existence not only of individual freedom, but of all the freedoms intertwined in that network. When being-for is not accepted as a responsibility, the reality of human existence is denied, which presupposes the being-for of all members of the community. The properly human and freedom, then, are seen as conflicting realities (p. 379). We are, Ratzinger will say, entitatively Trinitarian: man is the image of God, and therefore being-for, being-from, and being-with constitute his fundamental anthropology (cf. p. 385).

The famous meeting between Habermas and Ratzinger took place in Munich in 2004. Their interventions are collected in Dialectic of Secularization: On Reason and Religion (Encuentro, 2012). Mary Frances McKenna offers the following assessment: “It is not surprising that while both Ratzinger and Habermas ask reason and religion to learn from each other, their way of understanding this process is markedly different: Ratzinger seeks a learning process for faith in which they act as co-equal partners, mutually purifying each other of their pathologies. The pathologies of religion to which Ratzinger refers are marked in Habermas’s thinking on religion; however, the pathologies of reason seem to be mere anomalies for him. The corollary of the association between reason and faith that Ratzinger seeks is, for Habermas, an exchange-transaction between unequal participants: self-sufficient reason and that which is inextinguishable (p. 440). For Habermas, religion is, at most, an input for post-metaphysical thought. This is not the position of Ratzinger, who advocates a parity between faith and reason.

The dialogue with other philosophers (Camus, Vattimo, Kelsen, Rawls, Popper, Wittgenstein, etc.) remains unmentioned. Some of them, Guardini, Pieper, Spaemann, for example, have informed his thought. In any case, reading this book reveals the intellectual consistency of Ratzinger’s theology, revealing the contrasts, agreements, and disagreements he held with Western philosophy.

Related

Saint Joseph: Perpetual Smile

Luis Herrera Campo

19 March, 2025

3 min

The Silences of Saint Joseph: Eloquence of Love and Obedience

Javier Ferrer García

19 March, 2025

2 min

Saint Joseph: A Model of Fatherhood, Faith, and Protection

Patricia Jiménez Ramírez

19 March, 2025

4 min

With Human Life 2025

Jesús Ortiz López

18 March, 2025

4 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)