Five Years After the Start of the Pandemic

A Retrospective Analysis

Five years after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, Manuel Ribes, a member of the Bioethics Observatory, offers a sharp reflection on the events that preceded the spread of the disease and the shortcomings in preventive programs that should have helped mitigate it. Learning from the mistakes and omissions made may be the first step to prevent their recurrence.

Science as a Pretext

A few days ago, the Director of the Cabinet of the President of the Government presented the 2019 National Security Report to the Senate. This report, approved on March 4 by the National Security Council, radically modified the criteria previously established in the 2017 National Security Strategy, and considered the risk of a pandemic unlikely and of “low impact.”[1] A few days later, philosopher Javier Gomá, referring to the catastrophe experienced following the outbreak of COVID-19, stated that “science has been used as a pretext for exoneration of responsibility.”[2]

We have suffered an avoidable situation, and therefore it is necessary to rigorously consider the terms used by science and experts prior to this event. The first thing to be stated is that we have experienced a disaster. According to the United Nations, a disaster can be defined as “a serious disruption in the functioning of a community or society that causes a large number of deaths as well as material, economic, and environmental losses and impacts that exceed the capacity of the affected community or society to cope with the situation using its own resources.”[3] The threshold that the International Monetary Fund considers for the existence of an economic disaster is a 0.5% loss in GDP. In Spain, official death tolls range from the 28,000 recognized by the Ministry of Health to the 48,000 reported by the National Institute of Statistics[4]. The loss in GDP recognized for this year by the OECD is over 10%. The figures technically define the disaster, but its scale is better explained by the feeling of helplessness, anguish, and pain that all citizens have experienced with overwhelmed healthcare systems and people dying in anonymity.

Ecological Balance

Humans share planet Earth with animals and plants, but above all with viruses and bacteria. Between them all, there exists a certain equilibrium of coexistence, what we call ecological balance. The gut of every human being contains thousands of microbial species and billions of organisms: there are more individual microbes in each human gut than there are human beings on the face of the planet.

For an infectious disease to emerge in the human population, something must change in the ecological balance, and these changes are the main factors contributing to the emergence of risks. Viruses and bacteria have produced devastating pandemics throughout history as a result of these imbalances. The plague that swept through Europe in the mid-14th century killed more than a third of its inhabitants; in many populations, no one survived. The global influenza pandemic of 1918 affected a third of the world’s population and killed 50 million people, 2.8% of the total population.

Human activity increasingly impacts the ecological balance, increasing the possibility of the emergence of infectious diseases. And, despite great scientific and technological advances, in the 21st century, humanity cannot feel safe from this risk.

First Serious Warning at the Dawn of the 21st Century

For more than 40 years since the discovery of coronaviruses (HCoV-OC43 and HCoV-229E), they were considered only mildly harmful to human health. The rapid global spread of SARS-CoV in 2003 dramatically changed this paradigm.

This disease emerged as a large outbreak of atypical pneumonia in Guangdong in November 2002 and spread to Hong Kong, where a remarkable “superspreading” event occurred on February 21, 2003, leading to major outbreaks in Canada, Vietnam, and Singapore. SARS, until it was declared over in July 2003, recorded 8,422 cases and 916 deaths in 29 countries.[5]

The relatively high case fatality rate, the identification of super-spreaders, the novelty of the disease, the speed of its global spread, and public uncertainty about the ability to control it all contributed to widespread alarm. The possibility of similar events recurring is accepted as highly probable, and it is assumed that any new virus that bursts into our lives could be much more transmissible and lethal. [6]

In October 2004, the WHO published the document “SARS Risk Assessment and Preparedness Framework” [7], which contains a plan to prevent future similar episodes. In it, the WHO “strongly recommends that all countries conduct a risk assessment as a basis for contingency plans…” and also details other recommendations it addresses to National Health Authorities in all countries, such as “establishing an effective SARS response management process at all levels of government and defining the chain of command by assigning specific roles and responsibilities to key agencies” and “determining the most effective ways to provide human resources and logistical support to respond to outbreaks”; and even going into more detail, it urges “ensuring the supply of personal protective equipment, other essential equipment and pharmaceuticals, and logistics.”

Two years later, in 2006, the World Health Organization again drew attention to the situation by publishing the book “SARS: How a Global Epidemic Was Stopped”[8] featuring 33 experts who analyze everything related to this episode from different perspectives. Brian Doberstyn, author of the chapter “What Have We Learned from SARS?“, emphasizes as a first lesson that this time we were lucky, as certain characteristics of the SARS virus made containment possible. Typically, infected people did not transmit the virus until several days after symptoms began and were most infectious only on day 10 of illness, when they developed severe symptoms. Therefore, effective isolation of patients was sufficient to control the spread. If cases had been infectious before symptoms appeared, or if asymptomatic cases had transmitted the virus, the disease would have been much more difficult, perhaps even impossible, to control.

He also emphasizes that the role played by scientific advances in containment was not significant. Sequencing the virus’s genetic code, for example, helped identify the origin and spread of the virus, but did not actually help control it. Laboratory testing was useful in confirming SARS infections, especially in clinically atypical cases. But the most important factor in controlling SARS were the 19th-century public health strategies of contact tracing, quarantine, and isolation.

MERS: A New Episode That Reinforces the Potential Danger of Coronaviruses

In 2012, a new version of the coronavirus, dubbed MERS[9] (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome), was detected in Saudi Arabia. Initially, it had a mortality rate of 65%. It affected six countries in the Middle East, but imported cases were also reported in France, Italy, Germany, Tunisia, and the United Kingdom. The R0 infection transmission rate (the number of secondary cases each patient is expected to infect in a fully susceptible population) proved to be very low (around 0.6), which prevented the virus from reaching pandemic status.

2012: Germany develops a pandemic simulation to fine-tune its defense mechanisms

Drills are a proven effective tool for emergency preparedness. We are accustomed to conducting evacuation drills, rescue drills, military exercises, and so on. Simulations allow for the evaluation of work systems or processes with their operational tools, procedures, and formats, as well as for training or practicing decision-making and coordination. The process of evaluating the results should help identify critical management areas and aspects that need to be strengthened.

The German government asked itself how the state can develop preventive planning for these types of risks and, consequently, commissioned the Robert Koch Institute in 2012 to develop a simulation—a robust risk analysis—that would reveal the expected effects on the population, their livelihoods, public safety, and order in Germany.[10]

The risk analysis “Pandemic caused by the Modi-SARS virus” describes the global spread of a new pathogen originating in Asia: the hypothetical Modi-SARS virus. The scenario, the story that scientists drew up eight years ago, is based on their real-life experience with several past epidemics (influenza, HIV, SARS-CoV, avian influenza, H5N1). It comes astonishingly close to current processes: the hypothetical pathogen “Modi-SARS,” transmitted from a wild animal to humans somewhere in Asia, turns out to be transferable from person to person. Since infected people do not become ill immediately, but remain virus carriers, it takes time until the danger is recognized. In the scenario, two infected people fly to Germany. One attends a trade fair, the other resumes their studies after a semester abroad. These two “index patients” spread the virus through their extensive social contacts. Infections increase at an ever-increasing rate. In the simulation, the virus spreads in Germany over a period of three years. After three years, a vaccine should be available. During this time, three waves of infection occur, affecting many millions of Germans and resulting in more than seven million deaths, as experts assume a very high mortality rate of 10%.

Various types of measures are implemented in the simulation. The spread of the virus is slowed and limited by “anti-epidemic measures” such as quarantine for people in contact with infected individuals and isolation for highly infectious patients. School closures and cancellations of major events are also analyzed, measures without which the course of the virus would be even more drastic. The high number of treatments poses immense problems for both hospitals and medical residents, with many of those affected being treated at home or in emergency hospitals. The number of staff losses, above average due to the increased risk of infection, further aggravates the situation in the medical field. Bottlenecks are emerging for pharmaceuticals, medical devices, protective equipment, and disinfectants. The industry can no longer fully meet demand. Furthermore, the simulation reveals that the number of deaths among other sick people requiring clinical care is rising due to the overload in the healthcare sector; and the large number of infected people exceeds the capacity of intensive care units.

The knowledge gained was incorporated into the National Pandemic Plan. Among other actions, “planning aids” for hospitals, nursing homes, and senior citizens’ homes are formulated, the “stockpiling” of respiratory masks and other hygiene protection items is encouraged, as well as management concepts “for rapid procurement in the event of an emergency.”

It is important to note that all the information provided to the German Parliament is public, allowing for analysis by third countries. Among the conclusions worth highlighting is that the hypotheses used bear a high similarity to the characteristics of the current pandemic, proving that these were possible and probable conditions. He highlighted the importance of immediate action to limit the spread of the pandemic and highlighted the health bottlenecks. He also highlighted the importance of not paralyzing the country’s overall activity due to its serious economic consequences.

The Clarity of Dennis Carrol

In 2016, the Rockefeller Foundation mobilized international civil society, bringing together opinion leaders, experts in the field, researchers, representatives of international organizations, donors, and foundations from around the world to reflect on the obvious fact that the common thread running through almost all identified pandemic threats is that they are viral. And this poses a problem, because the virus turns out to be an enemy we don’t fully understand. The viruses we “know” are just the tip of the iceberg. According to the most recent viral research data, there are an estimated 500,000 undiscovered viral species in taxonomic groups that are capable of posing a threat to public health. Based on all these arguments, they launched a ten-year research project, The Global Virome Project, to develop a virus database. The warning issued by its president, Dennis Carroll, at the presentation is important: We live in an era where the long shadow of a catastrophic pandemic hangs over our world, threatening to dramatically alter the lives we live. The possibility that a single lethal microbe could suddenly emerge and sweep through every home, every community, without regard for national borders or social and economic status, is a fear shared worldwide. Global trends indicate that over the course of this century, the rate of emergence of new disease threats will continue to accelerate, as will the risk of a global pandemic.[11]

National Security Strategy 2017

In Spain, under the Presidency of the Government, the National Security Strategy is being drafted as a framework for National Security policy, a State Policy that conceives security broadly at the service of citizens and the State. The 2017 document[12], which has been in force for five years, warns that “this increase in risk situations associated with infectious diseases has come hand in hand with a rapid global change that is modifying the relationship between human beings and their environment […]. Spain, a country that receives more than 75 million tourists annually, with ports and airports that are among the busiest in the world, a climate that increasingly favors the spread of disease vectors, with an aging population and a polarized geopolitical situation, is not exempt from threats and challenges associated with both natural and intentional infectious diseases.” Consequently, it is necessary, “in addition to reducing the vulnerability of the population, to develop preparedness and response plans for health threats and challenges, both generic and specific, with a multisectoral approach that ensures good coordination of all the administrations involved, both nationally and internationally.”

GPMB Warns Again

The Global Preparedness Monitoring Board (GPMB) is an organization created in May 2018 by the World Bank Group and the World Health Organization to contribute to protecting the global population from health emergencies.

In its first annual report of 2019, it draws international attention to the risk of a pandemic caused by a lethal, rapidly spreading respiratory pathogen. It states, “The world is not prepared for a pandemic caused by a virulent, rapidly spreading respiratory pathogen. The 1918 global influenza pandemic affected one-third of the world’s population and killed 50 million people, 2.8% of the total population. If a similar outbreak were to occur today, in a world with four times the population and where travel to any destination is possible in less than 36 hours, between 50 and 80 million people could die.” In addition to these tragic levels of mortality, such a pandemic could cause panic, destabilize national security, and have serious consequences for the global economy and trade.” And it directs heads of government of all countries to “systematically conduct multi-sectoral simulation exercises to implement and sustain effective preparedness.”[13]

Recapitulating: What was known on January 1, 2020

Scientific consensus supports the idea that the emergence of a lethal pathogen with a high transmission capacity is increasingly likely. Containment, especially in the initial stages, cannot be achieved through medical means, as the characteristics of the pathogen and its mode of action are unknown. The 2003 SARS pandemic was declared over without a vaccine having been developed. Therefore, the available measures are contact tracing, quarantine, and isolation. Minimizing the scope of its spread requires immediate action, in which every day counts. Acting quickly when it comes to putting the machinery of a state into operation requires prior preparation. Therefore, both the WHO and other international organizations have required the governments of different countries to conduct risk assessment exercises as a basis for contingency plans. In Spain, furthermore, the “National Security Strategy” document required the development of preparedness and response plans. Simulation exercises are what allow for the detection and correction of bottlenecks in healthcare, logistics chains, and economic losses.

What was also known at the beginning of the year

On December 31, 2019, the WHO[14] office in China was informed of the existence of a new SARS-like pathogen, and on January 7, Chinese authorities reported that the virus had been isolated in a laboratory.

But unofficial reports about the outbreak began earlier: on December 30, Dr. Li Wenliang, an ophthalmologist at Wuhan Central Hospital, warned his colleagues about the advisability of using personal protective measures against the new pathogen, and the Chinese authorities forced him to publicly retract his statement. Something smelled fishy in authoritarian and censorious China, and the rest of the world had to be alert. It was a matter of days.

Some countries reacted in time. Thailand,[15] Korea,[16] and Singapore,[17] implemented measures to screen travelers from Wuhan on January 3, 2020; Singapore also strengthened surveillance for pneumonia cases nationwide. Japan,[18] joined the screening of travelers from Wuhan on January 7, and on January 16, implemented government-wide coordination mechanisms.

What was happening inside China was a mystery, but the spectacular images of the construction of a large field hospital and the export of cases did not match the official truth. By January 26, coronavirus cases had been detected in at least 10 countries, including France and the United States. Authorities in all nations should have been on alert and acted. Many nations acted in time and have been able to keep the pandemic under control.

There are also many in which their leaders have made good on the words of former Israeli foreign minister Abba Eban: “History teaches us that men and nations behave wisely once they have exhausted all other alternatives.”[19] And their citizens have paid the price with excessive mortality and economic decline.

*Article prepared in 2020.

Manuel Ribes – Institute of Life Sciences – Bioethics Observatory – Catholic University of Valencia

***

[1] EL PAÍS, 24 de junio de 2020 El Gobierno anticipa dos años la revisión de la Estrategia de Seguridad Nacional por el coronavirus

[2] Entrevista publicada en el diario El Mundo el 28 de Junio de 2020 («Los expertos han sido convocados de manera oportunista»)

[3] http://www.un-spider.org/es/riesgos-y-desastres#:~:text=Tal%20como%20,sus%20propios%20recursos

[4] cfr. El INE eleva a 48.000 las muertes en la pandemia con datos de todos los registros

[5] cfr. SARS: The First Pandemic of the 21st Century

[6] cfr. Learning from SARS: Preparing for the Next Disease Outbreak: Workshop Summary. Stacey Knobler, Adel Mahmoud, Stanley Lemon, Alison Mack, Laura Sivitz, and Katherine Oberholtzer – 2004

[7] WHO SARS Risk Assessment and Preparedness Framework – October 2004

[8] SARS : how a global epidemic was stopped. World Health Organization – 2006

[9] Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus: Epidemic Potential or a Storm in a Teacup? Alimuddin I Zumla, Ziad A Memish – 2014 – DOI: 10.1183/09031936.00227213

[10] Bericht zur Risikoanalyse im Bevölkerungsschutz 2012 Deutscher Bundestag 03. 01. 2013 (Deutscher Bundestag Unterrichtung)

[11] Guest Post | The Global Virome Project: The Beginning of the End of the Pandemic Era. Dennis Carroll 2016

[12] Estrategia de Seguridad Nacional 2017

[13] UN MUNDO EN PELIGRO Informe anual sobre preparación mundial para las emergencias sanitarias Junta de Vigilancia Mundial de la Preparación Septiembre 2019

[14] WHO Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) SITUATION REPORT – 1 21 JANUARY 2020

[15] WHO Novel Coronavirus – Thailand (ex-China) Disease outbreak news 14 January 2020 Novel Coronavirus – Republic of Korea (ex-China)

[16] WHO Novel Coronavirus – Republic of Korea (ex-China) Disease outbreak news 21 January 2020 Novel Coronavirus – Republic of Korea (ex-China)

[17] WHO Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) SITUATION REPORT – 4 24 JANUARY 2020

[18] 15. WHO Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) SITUATION REPORT – 1 21 JANUARY 2020 http://quarantine.doh.gov.ph/who-event-information-site-for-ihr-national-focal-date-of-information-posted-21-january-2020/

[19] Discurso en Londres (16 de diciembre de 1970); cfr. The Times (17 de diciembre de 1970)

Related

Jesus Saving Marriages and Families

P Angel Espinosa de los Monteros

17 March, 2025

3 min

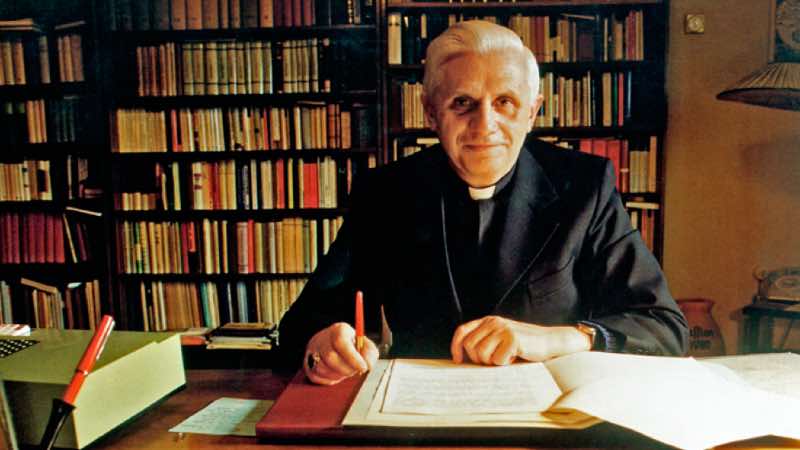

Ratzinger and the Philosophers

Francisco Bobadilla

17 March, 2025

8 min

The Meaning of Christianity: A Call to Hope and Transformation

Exaudi Staff

17 March, 2025

2 min

Equal Dignity between Women and Men: An Ongoing Commitment

Exaudi Staff

14 March, 2025

1 min

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)