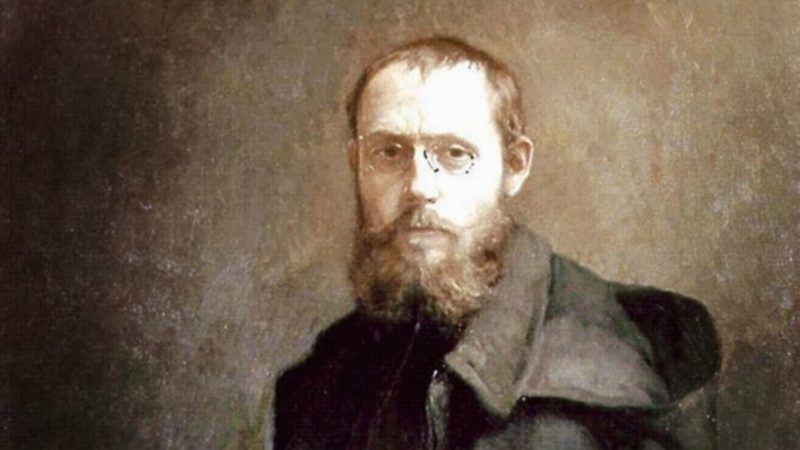

The greatness of soul of Charles Péguy

A journey between republicanism, socialism and faith: the greatness of soul of a mystic of his time

I still remember one afternoon in Lima a few years ago, when I read the voluminous poem Eva, by Charles Péguy (1873-1914), in a bilingual edition. Father Javier Cheesman, a professor of literature at the University of Piura, was passing by me. When he saw me with the book, he said, “There is so much that can be said about Eva” I was equally astonished at the beginning of the poem. I was not disappointed; the musicality of his verses, and the continuous contrasts of the ideas and intuitions that make up the poem, are a delight for the soul. Likewise, I return to Péguy, this time, in a biographical text, Charles Péguy. A socialist mystic? (Digital Reasons, 2022, Kindle edition) by Albert Llorca Arimany. I have clarified more of his human and intellectual profile, although I still do not fully understand it properly. I will continue investigating.

In Péguy, Llorca will say, “Republicanism in education and socialism in society converge, together with the active religious feeling that he noted in Jeanne d’Arc”. A good synthesis for a character as dense as Péguy. “He was a true convert; but not in the traditional way, abandoning family, culture and habits… Rather, he was a man who delves deeper, with his socialist baggage and from baptism, into family experience”. With the Dreyfus affair (1894) the foundations of his disagreements with his socialist colleagues (Andler, Sorel, Léon Blum, Herr, Jaurés…) are laid, from whom he separates himself in thought and works. He “postulated a mysticism of socialism far removed from all political manipulation, manipulations that bothered him greatly.” He was critical of the drift that the socialist politics of his time took, which he considered to be a “bourgeois cosmopolitanism,” a corruption of primitive socialism.

His philosophical thought was nourished by Bergson. He opted for life, rather than Cartesian abstraction. He considered family, country, work, and God to be fundamental; values that modernity would have betrayed in its attempt to emancipate itself from almost everything. “People often highlight the special way of being of Péguy’s character, very personal, through which he ran a thought far removed from any doctrinal system, since his vital impulse more than made up for it. In any case, he was a man attentive to the truth, feeling admiration for Victor Hugo and Pierre Corneille, writers who defended in their works honest people with values linked to the Christian sphere.” He was also a defender of the domains of reason, but not a rationalist. He will say: “The only thing we ask for – and we ask for it without any reservation, without any limitation – is not that reason be everything, but that there be no misunderstanding in the use of reason. We do not defend reason against the other manifestations of life. We defend it against the manifestations that, being other, want to take its place and degenerate into unreason.”

Péguy was strongly influenced by the sense of fraternity and friendship. He had a deep sense of commitment: seeing reality, thinking about it and acting accordingly. A selfless action, backed by a job well done and a deep desire to serve, alien to the cult of money and the spirit of utilitarian bourgeoisification that he saw in society. His proposal moved along other paths. For Péguy, Llorca will say, “to be great in the order of the flesh is to be a hero; to be great in the order of the spirit is to be a genius; To be great in the order of charity is to be a saint. And Joan of Arc reconciled these three orders and their respective greatnesses.”

Marxist revolution and class struggle? No. Péguy would rather say that “the true social revolution demands an ethical approach.” Hence “the revolution must necessarily be moral, or it will be nothing. And so must be true socialism, so that each human subject adequately practices his socialist action.” For Péguy, the revolution implies personal conversion. From a Marxist perspective, Péguy would be nothing more than a deluded utopian socialist. Seen, however, from the tragic history of the failed Marxist revolutions of the 20th century, Péguy is a prophet who reminds us that “ethics is essential in political life, and it cannot in any way replace the former.” The dignity of concrete people weighs more than class or the crazy pretensions of political messianisms.

Péguy is a testimony of vital coherence where the spiritual aspect links with temporal action. In the face of the impatience of those who want to break everything to change the world, he proposes hope that knows action and patience.

Enviar comentarios

Paneles laterales

Historial

Guardado

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)