Latin America has a peculiar identity that has emerged as a synthesis of indigenous and European cultures. What assessment should we make of Spain’s contribution to our own reality?

In 1992, the 500th anniversary of the “meeting of two worlds” was celebrated, as it was often said at the time. At that time, two polarized interpretations of Spain’s role in Latin American cultural synthesis emerged with great force. Some presented the Spanish conquest with enormous candor as an evangelizing and civilizing epic that had required the destruction – of the Great Tenochtitlán and many other communities – in order to eradicate paganism. On the other hand, there were those who claimed that there was nothing to celebrate. Spain, for this other group, was nothing more than an imperialist project that despotically subjugated indigenous communities, manipulating their religious sensitivity. Both interpretations are deeply burdened by ideology. As always, reality, in all its factors, is more complex than rationalist simplifications. Spain, without a doubt, contributed positively to the development of the Latin American cultural synthesis. And this does not prevent us from recognizing that there were also regrettable excesses. Pre-Hispanic communities had profound humanistic intuitions that they expressed in their poetry, in their community life and in their religiosity. However, violence and despotism also marked their worldview and their social praxis. The wheat and the weeds are permanently mixed.

In my opinion, the “reading key” to appreciate the positive role of Spain in the configuration of the Latin American cultural synthesis is, curiously, the same that we must have in order to appreciate the richness and beauty of pre-Hispanic cultures: an essential sympathy for the humanity of each person and of each people. In other words, if we do not start from an anthropology that allows us to understand that the wound of sin and the Redemption, carried out by Jesus Christ, are operating in human life and in the real plot of History, we can easily deform our understanding of the world. I immediately think of Queen Isabel of Castile, an extraordinary woman who was immersed in a historical-cultural context that is difficult for us to decipher today. Historical-critical research allows us to discover, with astonishment, that she was a woman truly moved by faith. However, her experience of faith was carried out within the limits of her fragile human condition and a particular cultural context. The result is that Queen Isabel, seen from the 21st century, requires the most holistic approach possible. Only by looking at the “polyhedron” of her life can we admire her “feminine genius”, her Christian virtues, and simultaneously recognize the limits imposed on her by the complex world of the 15th century.

A complete answer to this question would require many pages. I dare to point out a brief text by Archbishop Jorge Mario Bergoglio: “Historical interpretation must be made with the hermeneutics of the time; as soon as we use an extrapolated hermeneutics, we disfigure history and do not understand it. If we do not study the cultural contexts, we make anachronistic, out-of-place readings.”1 To this statement we must add everything that the Pontifical Magisterium teaches about the discovery of America. Pope Leo XIII published, for example, an Encyclical on this subject (Quarto abeunte saeculo). Pius XII recognized in multiple interventions the role of Spain in the evangelization of the new world. John XXIII will highlight the role of Mary in the first American evangelization. And then, more recent Pontiffs will broaden our awareness so that we can be grateful for the gift received from Spain and Portugal, and recognize, of course, also the limitations and sins of all parties.

To be thankful for the gift and to recognize the sin. It is easy to say, but it implies hard work on the part of everyone, isn’t it?

In both personal life and in the interpretation of History, we are all called to “conversion.” Only from a repentant heart that asks for help from the infinite Mercy of God is it possible to appreciate the truth about life and about History. Let us think for a moment about our parents. They give us life, they educate us, and surely, they make many mistakes along the way. How many of us do not have wounds that come from our own parents! It is only possible to thank them with humility for their fatherhood, if we have first lived the experience of recognizing our own limits and have discovered ourselves in need of compassion and mercy. What happens when we look at our own history without this personal process? We immediately fall into moralism. We immediately judge with enormous harshness those who hurt us and we see nothing good in them. The same thing happens in the arduous process of interpreting the History of America.

What can we thank Spain for?

Without a doubt, Spain was the vehicle through which we in Latin America came to know the Gospel. Likewise, Spain brought us many elements of its culture that were eventually reformulated in the Latin American Baroque. It is enough to visit Puebla, Quito or Lima to discover with astonishment that a new synthesis was gradually forged that is partially inherited from the Hispanic tradition. Now, the Baroque culture is not exhausted in the architecture of New Spain or in a certain way of speaking Spanish. The Baroque is a way of being, of existing, of celebrating life and even of facing death. It is our joyful complexity that reconciles diversity without suppressing it. It is our capacity to embrace and integrate. It is our way of affirming the human, but not in a rationalist way but by placing the heart at the center. In other words, the Latin American Baroque is Catholic modernity that embraces the Spanish and the indigenous in a new synthesis. Non-enlightened modernity, modernity open to the possibility of a Mystery that saves.

What made it possible to embrace the Hispanic legacy in the new Latin American baroque synthesis?

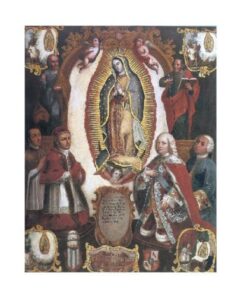

The Spanish crown wanted to evangelize, but it easily believed that the means to do so was the sword. The religious sense of the pre-Hispanic world longed for Jesus Christ. Many of the first evangelizers were surprised by the great willingness that appeared in the soul of the indigenous people to receive the Gospel. However, there were enormous problems due to the linguistic difference and the cultural disparity. The first ten years after the “conquest” were marked by few conversions and by great confusion. However, in 1531, something happened that took Spaniards and indigenous people by surprise: the Virgin Saint Mary of Guadalupe appeared to Saint Juan Diego in Tepeyac. She is the “first indigenous theology”; in other words, the Christian event bursts forth in an inculturated way and corrects the outlook of both indigenous people and Spaniards. Mary of Guadalupe reveals to us a non-imposing, non-“colonizing” way to promote social reconciliation and mestizaje. She teaches us the method of encounter to affirm the novelty of the gospel, and this is how a new people empirically emerges. There has long been an “anti-apparitionist” movement that claims that the Virgin of Guadalupe is an invention of the friars to evangelize and domesticate the indigenous people. What do you think about this? There are many ways to face the challenge of “anti-apparitionism.” Years ago I had the opportunity to have some dialogues in Querétaro and Mexico City with David Brading, who through his works presented some important objections to the Guadalupana and to Saint Juan Diego. Certainly the arguments by way of the physical examination of the image questioned him, but they did not completely convince him. However, two things I think impacted him more: I once told him that the theology contained in the Nican Mopohua cannot be explained with the theology existing in Spain at the beginning of the 16th century. The Nican Mopohua is a singular story that has contents that cannot be reduced to the theological education of the friars, mainly Franciscans, who arrived before 1531. Another fact also moved him: the empirical fact that, starting in 1531, a slow but real process of social reconciliation began. Those of us who have read the texts contained in The Vision of the Vanquished (UNAM, Mexico 1984) know well of the deep depression and the profound resentment that the Aztec natives suffered when they saw the Great Tenochtitlan collapse. Studying this moment in depth helps to recognize the “miraculous” character of the Guadalupe apparition, through one of its most profound effects: mestizaje. No European people at that time, upon encountering new cultures, she promoted processes of mestizaje and social reconciliation. The emergence of Mexico and Latin America is a true miracle.

So, Mary of Guadalupe also evangelized the Spanish. Is that so?

Saint Juan Diego, an indigenous layman, evangelized, that is, he brought the “Good News,” to Bishop Zumárraga, and then lived as a witness of Jesus and Mary until his death. I have the impression that Mary of Guadalupe has not yet finished this work. In a Spain and Latin America torn by strong divisions and polarizations, the Guadalupean message deserves to be more widely disseminated. New “Juan Diegos” need to appear to promote that Christianity is an event that reconciles and brings brotherhood. Pope Francis has called all ecclesiastical structures in America, Spain and the Philippines to the “Guadalupan Intercontinental Novena” in view of the Fifth Centenary in 2031. May God grant that we all prepare for it. May God grant that this may be a way of thanking Spain for all the good it has done for us, and of contributing to the recovery of a present and a future with hope.

___

1 J. M. Bergoglio – A. Skorka, On Heaven and Earth, Sudamericana, Bs. As. 2013, p. 186.