The City of Man

A deep analysis of modern liberalism and the particularity of modern man through the work of Pierre Manent

Pierre Manent is an academic of political philosophy. A disciple of Raymond Aron, he is knowledgeable about Leo Strauss and classical philosophy. In his book La Ciudad del Hombre (Santiago de Chile, IES, 2022; Preliminary study by Daniel J. Mahoney) he presents a substantial vision of the historical-intellectual trajectory of modern liberalism. He seeks to understand the particularity of modern man, for which purpose he studies Hobbes, Locke, Montesquieu, Hume, Kant, Weber, among others.

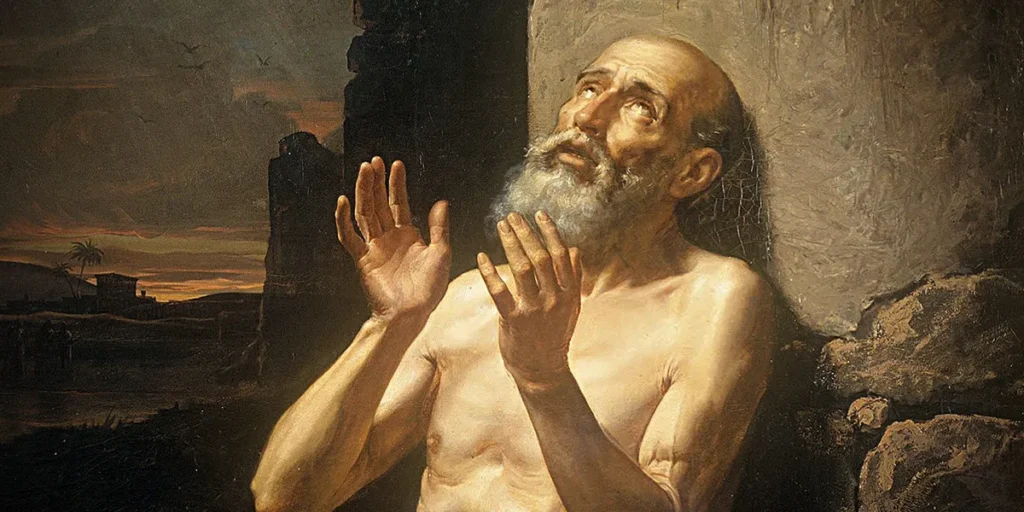

For Manent, modern man builds a “new world” to live in, neither “this world” nor “the other world”, but a third world, or third city, neither natural, like that of the Greeks, nor supernatural, like that of the Christians, but simply and purely human: the city of man (p. 343). Therefore, neither nature, expressed in Greek magnanimity; nor grace, expressed in Christian humility. A walk forward, stripped of all ties, whether personal or foreign. “He flees from the law and pursues it,” Manent maintains. “He flees from the law that is given to him and seeks the law that he gives himself. He flees from the law given to him by nature, God, or that he gave himself yesterday, and that weighs on him today as if it were someone else’s law. He seeks the law that he gives himself, without which he would be a plaything of nature, God, or his past. The law that he seeks does not cease to become, and continually becomes, the law from which he flees” (p. 347).

The modern man emphasizes freedom and rejects nature, not without contradictions that Manent points out with acute skill. Thus, for example, Montesquieu (1689-1755), in El espíritu de las leyes, weakens the authority of the ancients, as well as the idea of the best regime and the concept of virtue. He replaces them with the authority of the present moment: commerce and liberty (see p. 47). “What is called virtue in the republic is love of one’s country, that is, of equality. It is neither a moral nor a Christian virtue, but a political virtue” (p. 57). This political virtue is self-denial. It is love of the laws and the country. “This love, which requires a continuous preference for the public interest over one’s own interest, produces all the individual virtues” (p. 58). This concept of virtue “is not based on the control of the passions by reason, but rather on the absorption of passionate energy by and in a single passion: love of country and equality. It is, therefore, the love for a rule that oppresses and even afflicts” (pp. 61-62).

This political virtue, understood as self-denial, as a vocation of service in those who assume public office, is at the heart of the concept of “public servant”. We would like it to be so. We only have to look at the panorama of national and international politics to realise that the reality is different. James Buchanan, Nobel Prize winner in economics, with his theory of public choice showed that self-interest, selfishness, and opportunism nest in the human condition, independently of the public or private function assumed by the free agent. That is to say, neither trade nor public administration compensate for the lack of personal virtues in human beings.

Adam Smith, for his part, considers that “the desire to improve (improvement) is the central spring of human nature” (p.163). Before, Hobbes maintained that the general inclination of all humanity is the constant and relentless desire to acquire power and more power. “From Hobbes to Smith, the desire for power becomes the desire for purchasing power, whether to buy the products of labor or the labor itself” (p. 164). A desire to improve one’s condition either out of vanity (landowner, Teoría de los sentimientos morales) or out of satisfaction and interest (merchant, La riqueza de las naciones) (see p. 166). As can be seen, the barrier is rather low and remains pure self-interest.

For John Locke, nature gives man materials without value. The creative surplus is human labor, the origin of property. What determines and motivates human action for Locke is uneasiness, a term that expresses both restlessness and discomfort, unease. Hence, the nature of desire is to flee from any evil experienced in the present. It is not good that moves the human being, present discomfort is always stronger than future good. There is no space or time for noble ends. Fleeing from evil, that is the great motive (cfr. pp. 228-234).

The city of modern man is marked by libertarian emotivism: I want, I can, I do not harm others, therefore I do it. There is no other instance than desire. To this political conception, Manent proposes a city that is nourished by classical wisdom and Christian hope in Providence that jointly animated the Western soul. A city that seeks the good life of its citizens and knows how to unite the desire for achievement of modernity with the desire for Christian service. We have sufficient moral and political resources to continue our civic journey: action and hope, time and eternity.

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)