The face of aesthetics

Things are beautiful because they delight or please, because they are beautiful

Although the body opens up to higher manifestations of the human spirit or as Dr. G. Castillo would say, “the best of us ‘comes out’ to the exterior thanks to our corporality”; however, it is through the face that one takes charge of the uniqueness of a person. When one comes into contact with a person, vis to vis, knowledge acquires unsuspected dimensions and perspectives. Not only, one attend as a spectator as his biography unfolded up to that moment, but one also shares evaluations, interpretations, and foundations of some of his milestones. What is known by hearing is admitted to be iridescent by his being, sometimes expressed by his gestures, sometimes by his gaze, and sometimes by his voice inflections… which endorse an intense, different, and original world. It could not be otherwise because the encounter with a person is not a banal stumble. It is, rather, the beginning of the discovery of subjectivity, of a spirit that gives notice of a higher origin that adds plasticity, depth, and mystery.

In a certain way, something similar happens when one comes across aesthetics. This refers to beauty. Its usual way of manifesting itself is through painting and sculpture. Music and poetry have statutes that trace how they are appreciated. Nature has its thing: order, harmony, intensity, colour, and successful forms… attributes that are best appreciated when leaving the city for a weekend or on holiday. The rush of the days with their urgency that, when exhausted in themselves, do not favour perspective or the relationship with the environment, prevent us from conceiving – this verb supposes a certain elaboration – harmonious beauty, rather they force us to have a fragmented and reduced vision of it. Fragmented in terms of the most well-known artistic expressions and reduced because they confine it – in order of its manifestations – to the areas or places where they are exhibited. If aesthetics ends up being confined to specialized cloisters, then it is not feasible to acquire it in everyday life, even more so if one lacks a cultivated sensitivity.

Literature does not abound in techniques, styles or artistic modalities; on the contrary, it descends to the substratum and philosophical principles of beauty. It was not artists who were discussing, but thinkers who since Ancient Greece have reflected on aesthetics, interweaving and linking it to the conception of man, the universe and God. From the perspective of reasoning, aesthetics proposes the following dilemma: things are beautiful because they delight, or they please because they are beautiful. If it is maintained that things are beautiful because they delight, then it is admitted that beauty is in the subjectivity of the person, in which case, it is sensitivity that accredits beauty. Consequently, the measure of the estimation of the beauty of something will be linked to the greater or lesser intensity of the shudder and revival of the emotions that that perception awakens. In this sense, it could be concluded that beauty would be conditioned by the type of personality, excitability, the ability to respond sensitively to what is seen by an observer; as well as by his emotional labyrinths and concerns that prevent him from intentionally directing his senses towards his environment.

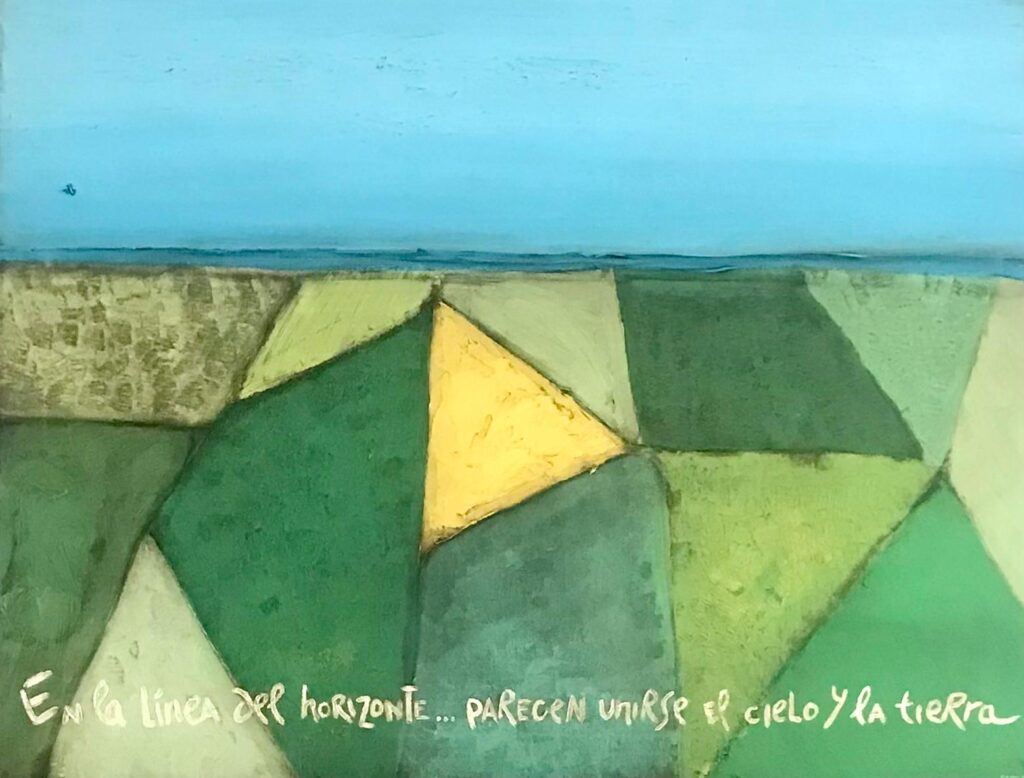

The other part of the dilemma indicates that beauty is constitutive of things, and, because they are beautiful in themselves, they summon, attract and invite us to contemplate them. In what way are they beautiful? Do they all have the same form of beauty? Do they allow themselves to be ‘caught’ exclusively by what the senses capture? Now, if all things are beautiful, being different, it is because they have common attributes that are not accidental. If this were not the case, beauty would be confined to groups, species or genera of things. Therefore, the aesthetic would have to be identified in what transcends, in what appears, in what is seen, in order to touch it from what it is, from its own being. But what things are is not the product of some sort of self-constitution: they have received their being. If they have received it, it means that they are creatures that participate in the nature and qualities of their Creator, one of which is their beauty.

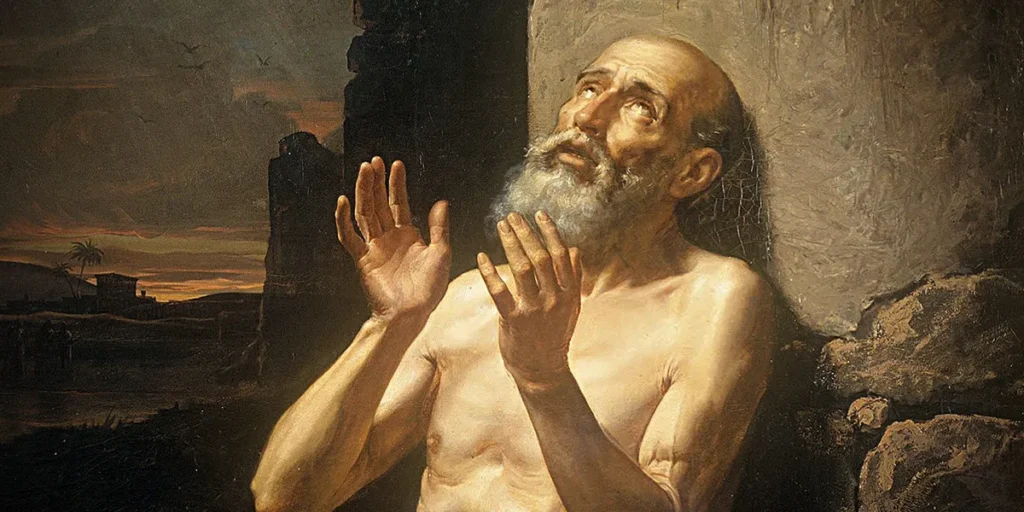

The dilemma, however, is not resolved by choosing one or the other option. What is fascinating about the study of aesthetics is that it reflects on the connection between both extremes: the beauty of things and the way in which man apprehends it. If things participate in being in different ways, the greater the fullness of the being received, the more beauty, then, the capture of the attributes of the being participated in does not suit primarily the senses, they are rather a channel for the intervention of human faculties: understanding and will. Capturing the harmony, integrity, simplicity, truth and clarity of things does not preach frivolity, rather it demands a certain willed effort so that the intellect – accompanied by sensitivity – penetrates the being of things and can contemplate them. Contemplation is not a mere seeing. It demands two conditions. First, putting in parentheses the vain subjectivity of feeling the origin of beauty; and, second, stripped of that attitude, respectfully opening up to the thing itself, allowing intimacy to make a journey from within so that, iridescent with the admiration that is born from the discovery of the Creator in it, it rests on the pupil of the eyes, so that the capture of beauty is the consequence of a look of loving gratitude.

Beauty is peacefully attractive. It is not perceived as provocative in the sense that it vehemently moves appetite or desire to the point that it obfuscates or disrupts passion; if it were so, the intellect could not penetrate what is seen: the sensitive effervescence revels in itself and, prey to that self-absorption, is denied to look outward.

In some way, beauty is union, harmony between my-being and the being of the thing that I contemplate. The thing gives notice of what it is and of the attributes that it possesses, in a certain despotic way; on the other hand, man – free by nature – has the power to act against his being. In man there is room for disharmony, the reversal of his purposes and the disordered use of his faculties. From this perspective, to acquire beauty implies a similarity between the thing and the person. This similarity calls for the display of his virtues and self-control so that he is less limited in allowing himself to be enraptured by beauty. When one lives in harmony, uniting with more intensity and complacency, with the beauty of things is not an onerous challenge, but rather it is the acquiescence towards plenitude.

The artist, for his part, possesses a special gift that allows him to capture beauty, illuminating the distinguishable essence of things, infusing them with a new form – the one seen by him in his mind – and making others perceive what he has seen and participate in its inner richness. Not only the artist can educe the beauty that things potentially have. The average citizen can also discover the hand of God in everyday life, in the smile of a child, in the tender look of an old man, in the ‘aha’ of a student who, after a long effort, understands the lesson; in the attentive and welcoming listening of a friend who is going through problems… In the raindrops that beat rhythmically on the roof of a house; the awakening of the sun, whose rays enter a room… Beauty is deep, mysterious, philosophical, but it knows how to express itself in simplicity, in goodness, in life and in kindness. This is the face of aesthetics that we have to discover.

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)